Oh, darkies have you heard it? Have you heard the joyful news?

Uncle Abraham's gonna free us, and he'll send us where we choose!

Cause the jubilee is coming, don't ye sniff it in the air?

And Sixty-Two is the Jubilee for the darkies everywhere

Oh, the jubilee is coming, don't ye sniff it in the air?

And Sixty-Two is the Jubilee for the darkies everywhere

Ol' Massa he had heard it, don't it make him awful blue?

Won't ol' Missus be a' raving when she finds it coming true?

Reckon there'll be a dreadful shaking, such as Johnny cannot stand

Cause Kingdom come is a' moving now, and a' crawling through the land!

Oh, the jubilee is coming, don't ye sniff it in the air?

And Sixty-Two is the Jubilee for the darkies everywhere

There'll be a big skeddadle now that the kingdom is a' come

And the darkies they will holler 'til they make the country hum

Oh we bress Ol' Uncle Abraham, we bress him day and night

And pray the Lord bress the Union folks and the battle for the right

Oh, the jubilee is coming, don't ye sniff it in the air?

And Sixty-Two is the Jubilee for the darkies everywhere

-Sixty-Two is the Jubilee

President Lincoln travelled to Washington D.C. his mood pensive. Three times had he travelled to the Federal Capital under tragic circumstances: The first time, the assassination of Lyman Trumbull had allowed him to be elected a Senator; the second, several Southern States had seceded and Civil War loomed over the United States. Now, he returned to the ruins left by one of the battles of that Civil War, which still raged on. Reminiscing of these journeys, and his escape when the rebels took the city more than a year ago, Lincoln reached Washington on the Fourth of July. In less than a year a lifetime of events had taken place, and with the end of the war still far away, more change was sure to come. Some Maryland Unionists, all of them fiery Unionists and supporters of the President, returned to the city and cheered him, while Black Contrabands timidly stood by, filled with hope for the liberation the Union Army promised.

Stopping before the ruins of the White House, Lincoln took a piece of paper from the inside of his iconic stovepipe hat. He briefly glanced at the smashed Statue of Liberty that was supposed to crown the Capitol, before starting a brief speech that was in actuality a broad declaration of the principles for which the Union fought. “We meet today in the battlefield of the Great Civil War we face, in the ruins of the capital of the Union we all cherish. The recent victory of our arms has advanced the cause for which thousands of our compatriots have given their last full measure of devotion. But the occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise -- as our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

His high pitched but clear voice continued. “Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history . . . The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We -- even we here -- hold the power, and bear the responsibility.

In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free -- honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. This way the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.”

Then, Lincoln proceeded to invoke the “considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God”, a passage previously suggested by Secretary of the Treasury Chase, before announcing the Emancipation Proclamation as the policy the Union would follow from that moment on. The legalistic, boring language of the Proclamation confused the spectators for a moment, but as it became clear that this meant a war for Union and Liberty, they broke into open cheers. “Glory to God! Glory! Glory! Glory!", "Bless the Lord! The great Messiah!” cried the Contrabands, profusely thanking God and Father Abraham, while the Marylanders, convinced by then that emancipation was needed to put down the rebellion, started to sing the Battle Cry of Freedom. Some even forgot their prejudices, and Americans, Black and White alike, sung together.

Lincoln then retired to a nearby building, one of the few that were still standing after the Confederates chaotically retreated, taking everything they could and burning everything they could not. Some of his colleagues, including members of the Cabinet, were present as Lincoln wearily sat down, physically tired from the journey and emotionally tired due to the war. He picked up a pen, but his hand trembled slightly. He put it down again, observing that “all who examine the document hereafter will say ‘He hesitated.’”, and that would not do because “I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper…. If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.” The President then took the pen and, with firm, confident handwriting, he signed the document.

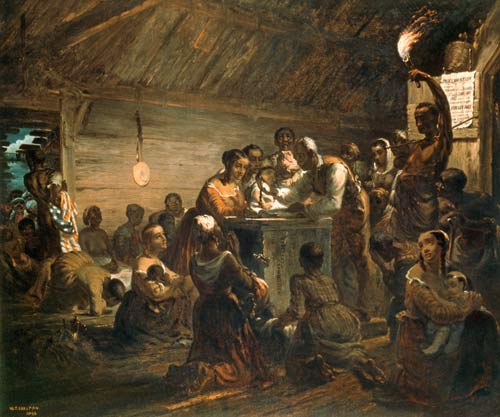

A famous painting commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation

“God Bless Abraham Lincoln!” the covers of the New York Tribune exclaimed joyously the next day, while throughout the North people held “huge rallies to celebrate the proclamation, marked by bonfires, parades with torches and transparencies.” "We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree," said Frederick Douglass, adding that “the cause of the slaves and the cause of the country” was now one and the same. A Pennsylvania man wrote Lincoln to tell him that “All good men upon the earth will glorify you, and all the angels in Heaven will hold jubilee,” and, in less eloquent but still heartfelt words, General Richard Oglesby called it “a great thing, perhaps the greatest thing that has occurred in this century”. Critical Radicals such as Stevens or Wade and supporters of the President such as Lovejoy or Sumner proclaimed their intention to stand “with the loyal multitudes of the North, firmly and sincerely by the side of the President.” The Proclamation, a “sublime act of justice & humanity,” thus arose all Americans to fight with renewed vigor for the Union.

This included, of course, Black Americans. Before the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued, Secretary of the Treasury Chase had asked Attorney General Speed whether “for the purposes of policy, colored men [are] citizens of the United States.” Speed then produced a document that constituted a harsh rebuke to “Dred Scottism”. First, it declared that, since the Constitution “says not one word, and furnishes not one hint, in relation to the color or to the ancestral race” of citizens, then all Black people were citizens of the United States once emancipated, thus entitled to all the privileges and protections furnished by that citizenship, which in turn “cannot be destroyed or abridged by the laws of any particular state”. Emancipated slaves were, consequently, “immediately entitled to the rights and privileges of a freeman”, and neither the Federal nor State government would have power to remand them to slavery because that “would amount to enslaving a free person.”

It’s possible that the legal foundations of the Emancipation Proclamation escaped many Blacks, but they plainly understood that in declaring emancipated slaves forever free and committing the Federal government to the protection of this liberty, the Proclamation had articulated, or at least implied, the big principles that would guide the Union throughout the rest of the war: Union and Liberty as war objectives, without which the war could not end; the creation of a national citizenship, with equality before the law regardless of color; and the creation of a benevolent national state, capable of enforcing emancipation and guaranteeing these rights. Thus, despite being founded on military necessity rather than morality, the Emancipation Proclamation provided both a basis for further attacks upon slavery and a pledge to sustain the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

Recognizing this, Black Americans joined in the chorus of celebrations, and memorable scenes of jubilee were observed throughout the nation. In Beaufort, South Carolina, contrabands sung “the Marseillaise of the slaves”: “In that New Jerusalem, I am not afraid to die; We must fight for liberty, in that New Jerusalem.” Northern Blacks celebrated with “intense, intelligent and devout declarations”, as well as well as cheers and music, including the Year of Jubilee: “And it must be now that the Kingdom’s Coming in the Year of Jubilee!” The “mere mention” of Lincoln’s name “evoked a spontaneous benediction from the whole Congregation”, because they “believe you desire to do them justice”, wrote an abolitionist to Lincoln. In Boston, a Black Congregation cheered the news, before joining in song: “Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea, Jehovah hath triumphed, his people are free.”

“Throughout the Sunny South, all darkeys heard the proclamation” as well, a former slave reported years after the war, doubtlessly still remembering that historic moment. In a contraband camp, an elderly Black man remembered how his daughter had been sold, but now “Dey can’t sell my wife and child any more, bless de Lord!” A young Black woman named Charlotte Forten, serving as a teacher in the contraband camps of the South Carolina sea islands, thought “it all seemed … like a brilliant dream.” In Kentucky, an area excluded from the Proclamation, slaves marched shouting hurrahs for Lincoln. Even in the Deep South, areas where the Union Army had not penetrated yet, the “grapevine telegraph” informed the slaves of the coming of Emancipation. For example, slaves in Mississippi organized Lincoln’s Legal Loyal League to spread the joyful news. Reports of “insubordinate” behavior multiplied, as many slaves in areas near the theaters of war refused to continue working unless paid wages. “We have a terrible state of affairs here negroes refusing to work…”, despaired a Tennessee slaveholder.

Black slaves found out about the Emancipation Proclamation through their "grapevine telegraph."

These slaves, far from meek victims who waited for their saviors, took an active role in the “friction and erosion” that Lincoln had warmed would fatally wreak slavery. W. E. B. Du Bois was right when he observed in his landmark

History of the Second American Revolution that the United States government was merely “with perplexed and laggard steps . . . following in the footsteps of the black slave.” Black slaves, whenever they could, escaped to the Union lines, thus emancipating themselves, and further undermining the institution and the Confederacy as a whole despite the frantic efforts of the rebels to quiet the Proclamation. Even slaves who stayed behind “often demanded shorter hours, improved working conditions, and better rations”. As one citizen had predicted in a letter to Lincoln, the promise of freedom made the slaves “come to you by the 100,000,” a situation that disrupted the Southern society and economy and enormously contributed to the eventual Union victory.

Together with the Proclamation, the Lincoln Administration rescinded a policy that prohibited the enticement of slaves away from their masters. What one newspaper had called the “Revolutionary Congress” had decreed that contrabands could not be returned to their owners, but for the moment the Armies were ordered not to “entice” the slaves to run away. General Butler, for example, was ordered to “permit no interference, by the persons under your command, with the relations of persons held to service under the laws of any state”, even as he was also prohibited from returning contrabands. From the moment of the Proclamation on, the Union Army worked to actively undermine slavery by enticing slaves away from their plantations. Halleck so instructed Grant, who had dutifully followed the policy of no return and no enticement, telling him that the new policy was “to withdraw from the enemy as much productive labor as possible.” Henceforth, whenever the Union flag marched, liberty would come with them.

More than 200 War Department agents started to tour the South to bring the news to the slaves, and also to make sure Union commanders respected and enforced the Proclamation’s dispositions, which included an invitation for the slaves to flee to the Union lines and “labor faithfully for reasonable wages”. Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, the War Department agent in charge of overseeing the “humane and proper” treatment of contrabands and the effective implementation of the policy in the Mississippi Valley, explained the logic of the Proclamation, which would weaken the rebels and “add to our own strength. Slaves are to be encouraged to come within our lines.” Accordingly, Union generals started to issue orders to this effect, like Grant, who ordered “all negroes, teams, and cattle” found in a raid to be brought in, or General Hurlbut, who instructed a subordinate to “bring in all able-bodied negroes that choose to come.”

Consequently, by the end of 1862 Southern masters began “noting the wholesale capture of large numbers of slaves”. Soon enough even the mere approach of the Union Army resulted in the escape of dozens of slaves, while every Union raid or march liberated hundreds. “The Yankees lately made a Raid,” one Mississippian wrote, “they committed great destruction of property & carried off over 800 negroes. I begin to fear that we are not safe.” Together with the turn towards a harsher war, the new policy meant the complete subjugation of the South, and that the new aim of the Administration was for it “to be destroyed and replaced by new propositions and ideas." A Southerner ruefully acknowledged this, listing the two Yankee policies: “to arm our own Negroes against their very Masters; and entice by every means this misguided Race to assist them in their diabolical program.”

Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and Missouri were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation. This led some to bitterly complain that "where he has no power Mr. Lincoln will set the negroes free; where he retains power he will consider them as slaves,” as the London

Times said. "This is more like a Chinaman beating his two swords together to frighten his enemy than like an earnest man pressing forward his cause”. But the idea that Lincoln did not liberate a single slave is factually wrong, for areas of Virginia, North Carolina, and the South Carolina sea islands were not exempted, and thus all slaves there were immediately emancipated. What’s more important, the Emancipation Proclamation accelerated the process of slave emancipation in the Border States, pushing them towards adopting abolition themselves, something that a military measure couldn’t have done without violating the Constitution.

For instance, a Kentucky man named Charles Hays felt compelled to liberate his slaves, and that he did, though it so disgusted him that he cursed Lincoln “for taking all you negroes away from me”, before skulking away and getting drunk while the freedmen celebrated. In Maryland, a gentleman told his slaves they were free to go if they so wished, but if they wanted to they could stay and work for him – for wages. Adopting a more paternalistic style, he gave each slave 10 dollars and told them to “Behave yourselves, work hard and trust in God, and you will get along all right. I will not hire anybody today, but tomorrow all who want to go to work will be ready when the bell rings.” Next day, all reported for duty, but now as freedmen, not slaves. Both of these examples took place in areas exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation.

Ornate copy of the Proclamation

The Union Army once again served as an ally of freedom, for many soldiers paid no mind to the exemptions outlined in the Proclamation. When a regiment of the Army of the Susquehanna moved out of Maryland to prepare for the next campaign, they decided to help many slaves escape first. Indignant slaveowners tried to reclaim them, but they were repulsed by Union soldiers who declared they were “no slave catchers” and “treated them to a little mob law”. When the slaveholders tried again with a sheriff, the soldiers simply grabbed them, threw them into a blanket, and then threw them high into the air. One soldier wrote home of the events, relishing the image of a southern aristocrat “being tossed fifteen feet in the air, three times, by Union soldiers—northern mudsills.” The slaveholders “got no slaves”, while the Union troops left for “pleasant ride to Richmond” with “fifteen free men and women on board.”

These examples show that, as historian James Oakes says, “the proclamation

increased the pressure on the Border States and

extended emancipation into areas previously untouched by federal policy”. Many Americans recognized this, and thus hailed the Proclamation as an anti-slavery triumph. Moreover, the Proclamation linked Emancipation with military victory, thus committing the Army and the war effort as a whole to Emancipation and assuring that the end of the war would bring about the complete destruction of slavery in the United States. Thus, Wendell Philipps exalted it because it treated slavery as a system to be abolished, and the

New York Herald declared that it inaugurated “a new epoch, which will decisively shape the future destinies of this and of every nation on the face of the globe.”

Giuseppe Garibaldi, the famous Italian republican, congratulated Lincoln, the “Heir of the thought of Christ and [John] Brown”, by telling him that “you will pass down to posterity under the name of the Emancipator! More enviable than any crown and any human treasure! An entire race of mankind yoked by selfishness to the collar of Slavery is, by you, at the price of the noblest blood of America, restored to the dignity of Manhood, to Civilization, and to Love”. A fellow revolutionary, Karl Marx, was more sober when he observed in a dispatch that “Up to now, we have witnessed only the first act of the Civil War—the constitutional waging of war. The second act, the revolutionary waging of war, is at hand.” So that such a Revolution may start in earnest, the Emancipation Proclamation also incorporated one very important measure – the enlistment of Black men as soldiers in the Union Army.

Though the Administration had allowed Black men, both free and contrabands, to serve in the Navy, and had turned a blind eye to the use of Black troops in Kansas and the quiet formation of some black regiments in the South Carolina sea islands, Lincoln remained hesitant about the idea of using Black soldiers, even Northern Free Blacks. He, for example, believed that “to arm the negroes would turn 50,000 bayonets against us that were for us.” But now he announced his intention to use this “great available and yet unavailed of, force for restoration of the Union.” “The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once”, the President believed. “And who doubts that we can present that sight, if we but take hold in earnest.” In the fall of 1862, the Government started to recruit thousands of Black men, starting with the formation of a “Corps d’Afrique” in the Mississippi Valley.

Congressional legislation had already included provisions that allowed the enlistment of Black Americans, the first being the Second Confiscation Act, ostensibly the legal justification for the Emancipation Proclamation, though Lincoln issued it under his own authority, as shown by his use of “I, Abraham Lincoln.” In May, 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act, which erased

free and

white from the requirements for able-bodied males to serve in the Armies of the Republic. Citizenship remained a requisite, but the Speed Opinion had declared Blacks citizens, and although the Proclamation itself did not do so, by allowing Blacks to serve as soldiers it implied that free blacks were already citizens. It was, an Ohio Congressman remarked, “a recognition of the Negro’s

manhood such as has never before been made by this nation.”

Furthermore, since being free was not a requirement, slaves could be recruited – even those held by loyal masters. The promise of liberty enticed many slaves, especially because their families would also be freed by their military service It took some time, but soon enough Union Army officers started to recruit slaves, even from plantations in the Border States, thus freeing them and granting then the citizenship the Speed Opinion had affirmed. This de facto conscription of slaves was not always voluntary, but it also became a potent weapon for the destruction of slavery in the Border States. In fact, nearly 60 percent of the Black soldiers recruited from the South came from the Border States, and 60 percent of Kentucky’s eligible black males had served in the Union Army by the end of the war. Military service thus provided a path for emancipation in states and areas exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, where Congress and the Administration had no constitutional authority to abolish slavery as an institution but could still liberate slaves.

The thing that most terrified the Southerners, however, was the idea of their slaves being taken, put into a Blue uniform, and sent to fight them. This was their bête noire, and soon enough the whole Confederacy denounced “Mr. Lincoln’s attempt to inaugurate a servile war”. Breckinridge, reportedly, “turned ashen in complexion” when he was told that the North was organizing Black regiments. The ailing Beauregard called for the “"execution of abolition prisoners” with a garrote, while Breckinridge, after recovering from the shock, pronounced it “the most execrable measure in the history of guilty man." Soon enough, the Confederacy decreed that in punishment for “crimes and outrages, aimed at inciting servile insurrection”, all Black soldiers and their White officers were to be tried and executed. The policy was not carried out to its full implications, but many Rebels took upon themselves to massacre captured black soldiers.

Thus, Black troops were "dealt with red-handed on the field or immediately thereafter," a brutal and criminal treatment that the Rebels hoped would discourage their enlistment. Many Southerners, and a good number of Northerners, were indeed skeptical of the capacities of Black men, believing that “those timid, fearful creatures, will not dare raise a hand against their owners”. But Black Americans, who had now a stake in the conflict because Union victory would result in Slave Emancipation, were eager to get “a chance to strike a blow for the country and their own liberty.” Agents of the War Department, including the indefatigable Lorenzo Thomas, started to organize Black regiments, but the greatest initiative was taken by two Union Governors: the young Kansas Governor Edmund G. Ross and Governor Andrew of Massachusetts.

Ross, a Kansas Jayhawker who had continuously pushed against the Slave Power, never recognizing the legitimacy of the Lecompton Government and continually denouncing them in his

Topeka Tribune, had been elected as the new governor after the coup against Lecompton was complete. Seeking to recognize the vital role of the unofficial Negro regiments who fought with his Jayhawkers, Ross approved the formation of a regiment, known as the First Kansas Negro Regiment, though it would later obtain the official designation of 57th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry. None other than John W. Geary, legendary for his actions when he was Kansas’ Territorial Governor, drilled them before he left for a post in the Army of the Susquehanna. Command of the First Kansas was turned over to Lindley Miller, an abolitionist son of a former New Jersey Senator.

As for the Massachusetts troops, Governor Andrew organized two regiments as soon as he obtained permission from the War Department. Prominent abolitionists were enlisted as commanders of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the young son of a prominent abolitionist family, was tasked with command of the 54th. “The North's showcase black regiment,” the bravery of the 54th Massachusetts would become legendary, weakening the prejudices of White Northerners and earning the respect and even the admiration of White Union soldiers. Marching into battle singing “we’re Colored Yankee soldiers!”, the First Kansas, 54th Massachusetts, and other regiments formed from the more than 200,000 Black Union soldiers, were essential in the eventual victory of the Union, and “helped transform the nation’s treatment of blacks and blacks’ conception of themselves”.

Indeed, at first many White soldiers resisted the very idea of Black regiments. "Woud you love to se the Negro placed on equality with me?" an Indiana private asked his father. "If you make a soldier of the negro you can not dispute but he is as good as me or any other Indiana soldier.” A New Jersey sergeant agreed, considering that arming slaves would be "a confession of weakness, a folly, an insult to the brave Solder." Nonetheless, and similarly to the Army’s acceptance of Emancipation as a military necessity, many soldiers acquiesced to the use of Black troops to aid the Union cause. "i wouldant lift my finger to free them if i had my say,” said an Illinois private, “but if we cant whip the rebils without taking the nigers I say take them and make them fite for us any way to bring this war to a close." Another Illinoisan expressed similar feelings, saying it would be "no disgrace to me to have black men for soldiers. If they can kill rebels I say arm them and set them to shooting. I would use mules for the same purpose if possible."

Resistance to Black recruitment reflected the Army’s initial opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation. Some soldiers welcomed it openly, such as a Pennsylvania man who recognized that the Proclamation made the war a contest not "between North & South; but one between human rights and human liberty on one side and eternal bondage on the other." A Minnesota comrade hailed the Fourth of July, 1862, as “a day hallowed in the hearts of millions of the people of these United States, & also by the friends of liberty and humanity the world over." An Iowa sergeant was now confident that "the God of battle will be with us . . . now that we are fighting for Liberty and Union and not Union and Slavery." Some, as already detailed, only accepted Emancipation as a weapon against rebellion, such as an Ohio officer who claimed to despise abolitionists but because "as long as slavery exists . . . there will be no permanent peace for America. . . . I am in favor of killing slavery."

Some soldiers felt betrayed by what they saw as a change in the purposes of the war. "I don't want to fire another shot for the negroes and I wish that all the abolitionists were in hell," said a New York artillery-man, while an Illinois professed that he “Can fight for my Country, But not for the Negros." A National Unionists loudly declared that "I did not come out to fight for the nigger or abolition of Slavery," and that Lincoln "ought to be lashed up to 4 big fat niggers & left to wander about with them the bal[ance] of his life." Men from the Border South felt betrayed as well, calling it “treachery to the Union men of the South,” and denouncing “the atrocity and barbarism of Mr. Lincoln’s proclamation”, attacks that were echoed by their soldiers, such as a Marylander who said he would no longer fight because "it really seems to me, that we are not fighting for our country, but for the freedom of the negroes," or a Missourian who approached treason when he suggested that the National Unionists “ougt to go in with the south and kill all the Abolitionists of the north and that will end this war."

Though it is clear that morale among some soldiers did decline, that probably had more to do with the eventual reversal in Union fortunes rather than with the Emancipation Proclamation itself. Indeed, most of these reports came from early 1863, rather than middle 1862 as one might expect. Quantifying the Army’s reaction as a whole is rather difficult, but analysis of the soldiers’ letters seems to show greater support for the Emancipation than opposition to it. In due time, the bravery of Black soldiers, the rise of the Copperheads, and the successes of the Emancipation policy as a weapon against the South would change the opinion of many soldiers.

An example is an Ohioan who at first declared that the Army “never shall . . . sacrafise [our] lives for the liberty of a miserable black race of beings”, but eventually came to regard Emancipation as "a means of haistening the speedy Restoration of the Union and the termination of the war." Soon enough, he became a Republican and by the end of the war he celebrated the creation of a nation "

free free free yes free from that blighting curs Slavery”. Marcus Speigel wrote to his wife that he would “not fight or want to fight for Lincoln's Negro proclamation one day longer," but after many months he wrote to her again, telling her that he was now in “favor of doing away with the . . . accursed institution. ... I am [now] a strong abolitionist." Even a Kentucky lieutenant who had once threatened to resign should the government move against slavery now said that " "The 'inexorable logic of events' is rapidly making practical abolitionists of every soldier . . . I am afraid that [even] I am getting to be an Abolitionist. All right! Better that than a Secessionist."

And so, the Army came to accept the idea of a war for both Union and Liberty, with Black soldiers as their comrades in arms. Some Union Generals faithfully executed the government’s policies, recruiting Black soldiers and enticing slaves, such as Grant or Butler. Despite his rather marked contempt for negroes, Sherman also executed the provisions of the Proclamation – though he would resist War Department pressure for Black recruitment. McClellan, also, and despite his evident disgust towards the policies of the government regarding contrabands, had executed its policies and freed slaves who came within his lines. Others, however, bitterly resented the shift towards Emancipation as a war policy, such as Buell, whose policies protecting slavery had almost caused insubordination among some of his officers.

The Emancipation Proclamation started the apotheosis of Lincoln as the Great Emancipator

After issuing the Proclamation, Lincoln met with McClellan, who had privately expressed disgust at “such an accursed doctrine as that of servile insurrection,” and furthermore saying that the “Presdt [is] inaugurating servile war, emancipating the slaves, & . . . changing our free institutions into a despotism”. According to Fitz-John Porter, the Emancipation Proclamation had been the act “of a political coward . . . ridiculed in the army— causing disgust, discontent, and expressions of disloyalty to the views of the administration.” McClellan took the opportunity given by Lincoln’s visit to lecture the President. The war, McClellan said, should be limited and not aimed at the “subjugation of the people of any state”; consequently, “neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of states or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment.” What Lincoln thought of this arrogant talk is unknown, for he coolly turned away without comment, leaving the next day for Philadelphia, which would remain the capital for the time being.

Lincoln had decided to visit the Army Headquarters in order to confirm rumors that the “McClellan Clique” had a “plan to countermarch to Washington and intimidate the President.” He also wanted to assess whether Anacostia was a great victory or a loss opportunity. He interrogated Allan Pinkerton with such skill that he did not realize he was being questioned, and concluded that McClellan had squandered an opportunity to finally destroy the Rebel army. This naturally increased his suspicions of McClellan being disloyal. In order to quiet down the “silly treasonous talk” among the officers of the Army of the Susquehanna and reassert the dominance of the civilian authorities, Lincoln decided to make an example of Major John Key, who had declared that the Army had not “bagged” the Confederates because “that is not the game.” Instead, “the object is that neither army shall get much advantage of the other . . . that both shall be kept in the field till they are exhausted, when we will make a compromise and save slavery.”

Key was summoned to Philadelphia, where Lincoln presented the evidence against him, ruling it “wholly inadmissible for any gentleman holding a military commission from the United States to utter such sentiments.” Lincoln cashiered him on the spot, later writing that it was his intention “to break up the game.” McClellan learned of the incident by a letter from Montgomery Blair. The Blair Clan as a whole was becoming alienated by the radicalization of the war, and they turned to McClellan as the only one who could steam the tide. Nonetheless, Blair urged McClellan to declare his support for emancipation, to “head off your opponents very cleanly.” Several subordinates also told him that opposing the Proclamation openly would be a “fatal error”. McClellan wrote to his wife that his friend Aspinwall had, too, advised him that “it is my duty to submit to the Presdt’s proclamation & quietly continue doing my duty as a soldier.”

On July 21st, McClellan issued a general order that reinforced the principle that civilian authorities made policy and the Army had to execute it: “Armed forces are raised and supported simply to sustain the Civil Authorities and are to be held in strict subordination thereto in all respects…. The Chief Executive, who is charged with the administration of the National affairs, is the proper and only source through which the views and orders of the Government can be known to the Armies of the Nation.” But McClellan finished his orders with an unsubtle reference to the next elections: “The remedy for political errors, if any are committed, is to be found only in the action of the people at the polls.” As the backlash to the Emancipation Proclamation among the people intensified, whether such a remedy was to be found in the fall elections of 1862 depended chiefly on the success of the new military campaigns against Corinth, New Orleans and Richmond, which started in earnest after the Emancipation Proclamation had radically changed the objective and prosecution of the war.