Im pretty sure the European countries had larger standing armies and practiced conscription, though Britain had a relatively small highly trained professional army, unlike America which early on feared that having a standing army leads to tyranny (and going by history and the present day American military industrial complex I'd say thats a quite accurate assessment).Well, I am hardly an expert myself, but I was always under the impression that European armies of the period have adapted much better to the appearance of large numbers of rifled weapons then the ACW militaries.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"IIRC IOTL there were multiple proposals to separate the Nickajack from the rest of Tennessee??

Yes, but that would actually backfire if our objective is a successful Reconstruction, since those areas are centers of Unionism during the war and Republicanism after it. In Tennessee and North Carolina, where Black votes aren't enough to produce electoral majorities, the White scalawags there are what allow Republicans to rule. To make them an independent state would be to cede power to the white racist majorities in the rump North Carolina and Tennessee.

So, the South is going to have a number of advantages OTL's didn't, and still lose - which will help convince everyone that they could not have won.

Even if D.C. is retaken by McClellan, it will have taken well over a year to do so. And, something tells me he'll botch it, but it's also possible he does and is therefore kept in charge longer than in OTL.

On the other hand, you have his OTL's comments about Lincoln, which is akin to a superstar complaining about his coach in pro sports. Except McCLellan is only a superstar in his own mind.

Such an outcome is bound to give a hit to the Lost Cause narrative, and destroy Southern will and morale even more, thus allowing the victorious North to impose its will with more ease. McClellan, since the press and the public are a lot less friendly to him on account of his disastrous Annapolis performance, is somewhat more cautious when it comes to dealing with Lincoln, who is also more assertive and has less patience for ineffective generals. Still, "original gorilla" and other classic insults still abound in McClellan's correspondence.

McClellan is in command? Then the campaign is fucked.

"I didn't lose. I mere failed to win!"

I hate that bastard so much.

Believe me, I don't like McClellan at all either.

"You have way more soldiers than them. Attack!"

"No."

"Mr. President, I have it on good authority that one Good Ol' Southern Boy is worth ten damnyankees, therefore technically the rebels outnumber us 1.5 to 1, sir."

"On whose authority?"

"Stonewall Jackson's, of course! I hear he's an honorable man, he wouldn't lie to another gentleman!"

"...why can't any of my generals hold a candle to Grant?"

Classic Little Mac!

"Mad, is he? Then I wish he would bite some of my other generals!"

IIRC, that quote is originally about James Wolfe during the Seven Years War, right?

Well, I am hardly an expert myself, but I was always under the impression that European armies of the period have adapted much better to the appearance of large numbers of rifled weapons then the ACW militaries. I mean, we have British and French use them to a good effect in the Crimea, French and Austrian adoption of tactics which emphasized heavy use of skirmishers and shock tactics to reduce the effect the rifled firearms, reducing the time the men spend in the beaten zone and the like. British did emphasize regular rifle practice, with special importance given to the range estimation. Yes, while it can be argued that with blackpowder smoke quickly making aimed fire much less effective, more intensive training would surely benefit both sides, even if it is limited only to skirmishers.

Im pretty sure the European countries had larger standing armies and practiced conscription, though Britain had a relatively small highly trained professional army, unlike America which early on feared that having a standing army leads to tyranny (and going by history and the present day American military industrial complex I'd say thats a quite accurate assessment).

Though the contemptuous remark of the American armies being "mobs chasing each other in the countryside" is likely apocryphal, it does reflect the fact that most American soldiers weren't consummate professionals or people induced by a strong national state, but volunteers who made up for their lack of training and discipline with patriotic determination and courage. Good for resisting attrition campaigns, but bad for adopting new tactics or creating specialized units. I will try to incorporate tactical changes in future updates, though.

Btw, soon guys

FUCK YES wreck Johnny Reb, General Grant! FOR THE SECOND AMERICAN REVOLUTION! FOR AMERICA!

Though the contemptuous remark of the American armies being "mobs chasing each other in the countryside" is likely apocryphal, it does reflect the fact that most American soldiers weren't consummate professionals or people induced by a strong national state, but volunteers who made up for their lack of training and discipline with patriotic determination and courage. Good for resisting attrition campaigns, but bad for adopting new tactics or creating specialized units. I will try to incorporate tactical changes in future updates, though.

Yes, the main problem they had was a rather small size of the Prewar army, not helped with that already small number of men each going their own way, as well as the initial belief that the war is going to be a short one, so the training of the volunteers was not all it could be. Still, it is interesting to note, that we would see employment of field fortifications as early as Bull Run, if on a small scale, which means that people did recognize the value of defenses, and the advantages they could give.

So, first we need to recognize that smoothbore firearms are still present in substantial numbers, and we will not see until 1863 or so, rifled firearms being availlable in sufficient numbers. Second, there seems to be a lack of organized training system, with very little attention given to rifle practice, with more focus on drill then anything. Also, another failing that I can not understand, is the fact that generally individual regiments rarely, if ever, received reinforcements, and instead they would raise new formations, which means that newly raised regiments rarely had a pool of experienced of personnel to spread the knowledge.

Maybe the best that could be done, if we consider the situation both sides are in, where armies have grew large rather quickly, and lack sufficient numbers of trained and experienced personnel, is to focus the training on a smaller portion of men? So each Regiment has a dedicated company of skirmishers, which undergo more extensive training in marksmanship at some sort of dedicated training establishment, and they then spread their knowledge as much as possible to the rest of their parent regiment? The rest of the regiment could be employed in Battalion or even Company sized attack columns, similar in a way to the French and Austrian assault tactics of the time, Stoßtaktik, where these assault columns would performs bayonet charges while covering fire would be provided by the skirmisher screen in front or on their flanks. IMHO this does seem rather doable, and while Stoßtaktik failed miserably in the Austro-Prussian War, neither Union nor Confederate troops are facing troops armed entirely with breachloading firearms, so I do feel rather sure in saying that this sort of tactics could still be of value.

Good work so far, very interesting, keep it up.

The US lacked experienced soldiers, and didn't use the ones it had very well.

Regiments were fundamentally independent, and had their own reputations they wanted to hang onto - you don't have the British style regimental system, where the different battalions of the regiment share the one name, and veterans can be shared between the battalions pretty naturally.

The whole thing is a genuinely hard problem. Even if the federal government came up with e.g. a training plan to turn volunteers into soldiers, what's to make the states follow it? Where are the trainers coming from? Commanding officers will resist giving up good men to go hundreds of miles away to train recruits that they might never see, that's for sure...

Regiments were fundamentally independent, and had their own reputations they wanted to hang onto - you don't have the British style regimental system, where the different battalions of the regiment share the one name, and veterans can be shared between the battalions pretty naturally.

The whole thing is a genuinely hard problem. Even if the federal government came up with e.g. a training plan to turn volunteers into soldiers, what's to make the states follow it? Where are the trainers coming from? Commanding officers will resist giving up good men to go hundreds of miles away to train recruits that they might never see, that's for sure...

I forget the name of the department, but the bureau in charge of acquiring and supplying guns and ammo was notoriously stingy even going up to the Spanish-American war, though not without reason. The military budget was rather tight, and besides that you have the predominant military doctrine of the time (even in Europe) that soldiers couldn't be trusted to not waste what limited ammunition they had, and this idea persisted into ww1. Its why you see magazine cut offs in pre-ww1 rifles, so the soldiers would single feed at their officers direction and only be allowed to pour lead down range at said officers permission.Second, there seems to be a lack of organized training system, with very little attention given to rifle practice, with more focus on drill then anything.

This is precisely what the zouaves where supposed to be under Ellsworth's leadership, but more often than not zouave regiments where created by states just to look fancy rather than fulfill a special tactical niche.So each Regiment has a dedicated company of skirmishers, which undergo more extensive training in marksmanship at some sort of dedicated training establishment, and they then spread their knowledge as much as possible to the rest of their parent regiment?

ITTL though Ellsworth is very much alive, and while McClellan is pussyfooting around Ellsworth will be hard at work drilling the men into shape

Got a question if the us army was that small and not good how did they DESTROY MEXICO in the mexican american war?

Because Mexico had an even worse army riddled with corruption, and inferior weapons and ammunition.Got a question if the us army was that small and not good how did they DESTROY MEXICO in the mexican american war?

The quartermaster corps was so corrupt they sold gun power and mixed the rest with charcoal, resulting in very poor powder.

They didn't destroy Mexico, they essentially took the major port of Veracruz and then marched on the National Capital and took that as well as blockades and some fighting which was closer to Denver than to Mexico City The major difference is that unlike the 1838 Pastry War and the 1862 French Intervention, the US didn't want debt payments, they wanted Mexican Territory.Got a question if the us army was that small and not good how did they DESTROY MEXICO in the mexican american war?

I'd argue that Britain, France, the United States and even some second tier European powers could have done what the US did in taking Mexico City at any time from Mexican independence until probably the 1880s.

In some ways the US was more unified under the Continental Congress than Mexico was in 1848. and President Santa Ana doesn't help. Sometimes I think that killing Santa Ana as a baby may do more for Mexico than killing Hitler as a baby would do for Germany.

I forgot the level of corruption as well. Also, at the very beginning of the Mexican American war, the US and Mexico were fighting with more or less the same weapons (1810s muskets). By the end, most of the Rifles and handguns for the American troops were of a brand new technology (Springfield Rifles, Colt revolvers, etc) that the Mexicans didn't even have the industry to directly copy. In fighting the Americans the Mexicans had most of the disadvantages they had fighting the Texans, and then some.Because Mexico had an even worse army riddled with corruption, and inferior weapons and ammunition.

The quartermaster corps was so corrupt they sold gun power and mixed the rest with charcoal, resulting in very poor powder.

One reason was the inferiority of the Mexican Army: while the common Mexican infantryman impressed their American opponents, the money poured into the army was put into the pockets of the Mexican Army higher ups, leading to a poorly armed and poorly equipped army. In contrast the U.S. Regular Army had already undergone major reforms in regards to professionalism after the War of 1812 and had highly trained engineers, excellent artillerymen and a capable Quartermaster Department.Got a question if the us army was that small and not good how did they DESTROY MEXICO in the mexican american war?

Comparing the US regular army to a European Army? The U.S. Army does not come out looking too good. The U.S. Army was far too small - it numbered only 7,365 soldiers at the outbreak of the Mexican-American War (16,367 at the start of the ACW). It was mostly scattered in company size across small posts to guard the coastline and watch the frontier. Hence, the U.S. Army was not very well practiced with large scale maneuvers. Officers in the army tend to be rather old due to the lack of vacancies and with no retirement program, most officers stayed in service until they were too old or physically incapable of carrying out their duties. Target practice and marksmanship training was also rather lacking.

The explanation I heard of for that particular failing (I forget where, but I think it was Catton), was that since regiments were raised by the States, raising new regiments allowed the governors more opportunities to exercise patronage through appointing officers. A prime argument for federalizing recruitment, but what can you do?Also, another failing that I can not understand, is the fact that generally individual regiments rarely, if ever, received reinforcements, and instead they would raise new formations, which means that newly raised regiments rarely had a pool of experienced of personnel to spread the knowledge.

The explanation I heard of for that particular failing (I forget where, but I think it was Catton), was that since regiments were raised by the States, raising new regiments allowed the governors more opportunities to exercise patronage through appointing officers. A prime argument for federalizing recruitment, but what can you do?

One of the other big problems was that most regiments were simply formed, then whittled away by desertion, disease and casualties until they were rendered combat ineffective. A regiment could theoretically be 1000 men strong, but quickly degrade to 800, and apparently most had been whittled down to only 400 men by their first year of service. Worse was when those regiments service was up they would normally be completely disbanded and the men shuffled off to other new regiments rather than simply filling the regiments up with new recruits. IIRC only Wisconsin had the machinery in place to send replacements out for battle casualties to keep regiments remotely up to strength.

Apparently during the Overland Campaign regiments had shrunk to such a state that when Grant ordered the heavy artillery battalions into the field they - having seen almost no combat - were so large that other regiments would joke "which brigade are you?" when they saw them march by.

Question: Has the CSA made any incursions into New Mexico like in OTL, or is Beckinridge wise enough to realize that an invasion of California is madness?

I'd call it gallows humor, but I don't think they have enough rope left.Apparently during the Overland Campaign regiments had shrunk to such a state that when Grant ordered the heavy artillery battalions into the field they - having seen almost no combat - were so large that other regiments would joke "which brigade are you?" when they saw them march by.

FUCK YES wreck Johnny Reb, General Grant! FOR THE SECOND AMERICAN REVOLUTION! FOR AMERICA!

Vive la Révolution !

Yes, the main problem they had was a rather small size of the Prewar army, not helped with that already small number of men each going their own way, as well as the initial belief that the war is going to be a short one, so the training of the volunteers was not all it could be. Still, it is interesting to note, that we would see employment of field fortifications as early as Bull Run, if on a small scale, which means that people did recognize the value of defenses, and the advantages they could give.

So, first we need to recognize that smoothbore firearms are still present in substantial numbers, and we will not see until 1863 or so, rifled firearms being availlable in sufficient numbers. Second, there seems to be a lack of organized training system, with very little attention given to rifle practice, with more focus on drill then anything. Also, another failing that I can not understand, is the fact that generally individual regiments rarely, if ever, received reinforcements, and instead they would raise new formations, which means that newly raised regiments rarely had a pool of experienced of personnel to spread the knowledge.

Maybe the best that could be done, if we consider the situation both sides are in, where armies have grew large rather quickly, and lack sufficient numbers of trained and experienced personnel, is to focus the training on a smaller portion of men? So each Regiment has a dedicated company of skirmishers, which undergo more extensive training in marksmanship at some sort of dedicated training establishment, and they then spread their knowledge as much as possible to the rest of their parent regiment? The rest of the regiment could be employed in Battalion or even Company sized attack columns, similar in a way to the French and Austrian assault tactics of the time, Stoßtaktik, where these assault columns would performs bayonet charges while covering fire would be provided by the skirmisher screen in front or on their flanks. IMHO this does seem rather doable, and while Stoßtaktik failed miserably in the Austro-Prussian War, neither Union nor Confederate troops are facing troops armed entirely with breachloading firearms, so I do feel rather sure in saying that this sort of tactics could still be of value.

Good work so far, very interesting, keep it up.

The fact that regiments were not reinforced to full strength but that rather new regiments were created always baffled me. It seems to make no sense, and it is definitely an oversight that caused great confusion and inefficiency. I do think the idea of a dedicated skirmisher bataillon is very interesting, and it could be especially useful once the war becomes one of trenches.

Thank you for your support!

The US lacked experienced soldiers, and didn't use the ones it had very well.

Regiments were fundamentally independent, and had their own reputations they wanted to hang onto - you don't have the British style regimental system, where the different battalions of the regiment share the one name, and veterans can be shared between the battalions pretty naturally.

The whole thing is a genuinely hard problem. Even if the federal government came up with e.g. a training plan to turn volunteers into soldiers, what's to make the states follow it? Where are the trainers coming from? Commanding officers will resist giving up good men to go hundreds of miles away to train recruits that they might never see, that's for sure...

As it often happened during the war and Reconstruction, the US' federalism works against it, since most regiments are state ones. Some even had conditions, demanding to serve only within their states. Since the Civil War represented a massive expansion of Federal authority, a national training program may be instituted in the future, but for now the army is probably stuck with this old and inefficient system.

I forget the name of the department, but the bureau in charge of acquiring and supplying guns and ammo was notoriously stingy even going up to the Spanish-American war, though not without reason. The military budget was rather tight, and besides that you have the predominant military doctrine of the time (even in Europe) that soldiers couldn't be trusted to not waste what limited ammunition they had, and this idea persisted into ww1. Its why you see magazine cut offs in pre-ww1 rifles, so the soldiers would single feed at their officers direction and only be allowed to pour lead down range at said officers permission.

This is precisely what the zouaves where supposed to be under Ellsworth's leadership, but more often than not zouave regiments where created by states just to look fancy rather than fulfill a special tactical niche.

ITTL though Ellsworth is very much alive, and while McClellan is pussyfooting around Ellsworth will be hard at work drilling the men into shape

Taking into account that soldiers were known for firing their arms just to test them, the idea of limiting ammunition until battle doesn't seem to crazy. On the other hand, Ellsworth is alive, as you point out, and he will play a larger role in the future!

Got a question if the us army was that small and not good how did they DESTROY MEXICO in the mexican american war?

Because Mexico had an even worse army riddled with corruption, and inferior weapons and ammunition.

The quartermaster corps was so corrupt they sold gun power and mixed the rest with charcoal, resulting in very poor powder.

Basically this. The US Army was not the best in the world, but the Mexicans were very divided and had terrible equipment. The result was that most of the time they fought against each other or where more worried with internal intrigue than beating the Americans.

They didn't destroy Mexico, they essentially took the major port of Veracruz and then marched on the National Capital and took that as well as blockades and some fighting which was closer to Denver than to Mexico City The major difference is that unlike the 1838 Pastry War and the 1862 French Intervention, the US didn't want debt payments, they wanted Mexican Territory.

I'd argue that Britain, France, the United States and even some second tier European powers could have done what the US did in taking Mexico City at any time from Mexican independence until probably the 1880s.

In some ways the US was more unified under the Continental Congress than Mexico was in 1848. and President Santa Ana doesn't help. Sometimes I think that killing Santa Ana as a baby may do more for Mexico than killing Hitler as a baby would do for Germany.

This as well. Mexico was very weak and divided... poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.

Question: Has the CSA made any incursions into New Mexico like in OTL, or is Beckinridge wise enough to realize that an invasion of California is madness?

Well, none of my sources actually mention the campaign, so I'd have to rely in Wikipedia for information. With that in mind, I decided to butterfly it away. Breckinridge would probably be smart enough to see that the Confederacy has little hope of successfully taking California and their prospects for occupying it are even bleaker, so he probably kept the troops close so that they can fight the Federals close to home.

I'd call it gallows humor, but I don't think they have enough rope left.

Impressive how people could joke like that after living through literal hell.

There is a reason that the US chose war with Mexico over war with Britain in the 1840s and it wasn't just that the Slave States were more desperate for land...Basically this. The US Army was not the best in the world, but the Mexicans were very divided and had terrible equipment. The result was that most of the time they fought against each other or where more worried with internal intrigue than beating the Americans.

This as well. Mexico was very weak and divided... poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.

One stat about Mexico from Wikipedia. Until the presidency of Lazaro Cardenas, each president had remained in office an average of fifteen months, which is actually *worse* than it sounds considering that *includes* Profirio Diaz whose Presidency went from 1884-1911 (plus time in 1876 and from 1877-1880. )

And in 1861, the United States was on its 16th President in about 75 years, Mexico was on its 26th President after having been independent about half as long (and with *many* of them somehow service 2-3 times...

List of heads of state of Mexico - Wikipedia

Chapter 28: As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free

Following the Second Maryland Campaign, General George B. McClellan was called to Philadelphia to face the Committee on the Conduct of War, which wished to inquire why he had failed to energetically follow up McDowell’s successes and break out of Annapolis. Republican Senators, fed up due to lack of success and inaction, sharply attacked the Young Napoleon. When McClellan explained that he wanted secure supply lines and a route of evacuation should the rebels manage to overwhelm him with their supposedly superior numbers, the Radical Zachariah Chandler of Michigan pointedly replied “If I understand you correctly, before you strike the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room so that you can run in case they strike back?” Senator Ben Wade sardonically added that McClellan wanted that in case he gets scared.

McClellan promptly launched into a winded speech about the art of war and the necessity of supply lines and evacuation routes. After he finished, Wade simply told him that what the people wanted and needed was “a short and decisive campaign”. McClellan then left, and although he told a friend that Wade had been courteous and that the Committee was “anxious to sustain him, and to cooperate”, the reality was other. Indeed, after Wade asked him what he thought of the “science of generalship”, Chandler frankly admitted that he did not know much, “but it seems to me that this is infernal, unmitigated cowardice”.

Lincoln probably agreed. The months between March and June, 1862 represented his low point as commander in chief. During these months, the only major Union actions ended in defeat: Grant failed to take Corinth, Farragut to take New Orleans, and both Buell and McClellan refused to act. The Emancipation Proclamation remained in a drawer. His messages to his generals reflect Lincoln’s profound discouragement. He practically begged Buell to move into East Tennessee, where “our friends . . . are being hanged and driven to despair, and even now, I fear, are thinking of taking rebel arms for personal protection. In this we lose the most valuable stake we have in the South.” Buell’s failure to do so “disappoints and distresses me”. Grant also had to deal with a barrage of criticism following the Battle of Corinth, and a weary Lincoln seemed less eager to defend him.

Nonetheless, the greatest sign of Lincoln’s despairing mood is his comment to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. “General, what shall I do?”, the President said, “The people are impatient; Chase has no money… No general will act. The bottom is out of the tub. What shall I do?” Indeed, what should he do? McClellan, again showing his timid behavior, perhaps afraid of tarnishing his reputation by defeat, refused to move until meticulous preparations were set in place. This earned the ire of Congressional Republicans, who had hoped that McClellan could live up to his vainglorious promises and, as a Radical newspaper had once predicted, “infuse vigor, system, honesty, and fight into the service.” But the image of McClellan as God’s instrument to save the Union, which partially appeared as a reaction to McDowell’s supposed slowness, was crumbling away.

Republicans had once expressed similar impatience with McDowell, but the fallen general’s delay was often well-founded, and though neither of his campaigns were spectacular successes per se, he had achieved something, retaking Baltimore and setting the stage for a campaign for Washington. But McClellan seemed to simply differ, always asking for more troops and expressing fears of secret rebel legions. " 'Young Napoleon' is going down as fast as he went up," observed an Indiana Republican, and indeed, people who had once supported McClellan now vilified him. A bitter press started to assail him more harshly as well. Perhaps the most damaging fact was that McClellan’s relationship with the Administration was now strained.

In special, Secretary of War Stanton and McClellan quickly grew to detest each other. Stanton was growing closer to the Radical Republicans, and he shared their vision of McClellan as a coward and wanted the war to be pursued with more vigor. “We have had no war. We have not even been playing war . . . this army has got to fight or run away . . . the champagne and oysters on Havre de Grace must be stopped”, he declared. Whereas McClellan had at first been delighted with Stanton’s appointment, saying it was “a most unexpected piece of good fortune”, now he denounced Stanton as “without exception the vilest man I ever knew”, a traitor “willing to sacrifice the country & its army for personal spite, allied with abolitionist hell hounds.”

Zachariah Chandler

McClellan’s relationship with the President was also deteriorating. At first Lincoln was willing to give McClellan an opportunity. When the General asked that the President protect him from public pressure that would “push me and this noble army into hasty and disastrous action,” Lincoln assured him that McClellan would have his support, though he added that the demands of Republican politicians were "a reality, and must be taken into account”. But soon enough, Lincoln was convinced that he needed to “take these army matters in his own hands”. The main factors behind this were the fact that Lincoln’s confidence on professional military men had been eroded, thus he was more willing to assert himself, and also that he did not believe McClellan’s reports of Confederate numbers anymore, which was mostly due to the Annapolis disaster.

The opinion of the Committee of War, which declared that the Commander in chief “must, by law, command” and not continue “this injurious deference to subordinates”, spurned Lincoln into action. Saying that he “would like to borrow the Army of the Susquehanna, if General McClellan would not use it”, Lincoln drafted Special Orders No1 and No2 on April 2nd. These orders called on the “Land and Naval forces” to move against the “insurgent armies” before or on June 14th – the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Lincoln then summoned McClellan to an informal council of war, and inquired for his plans of action against the rebel army. Sullen and almost insubordinate because he felt attacked, McClellan simply declared that “the case was so clear a blind man could see it”, and, he whispered to Meigs, he feared Lincoln would leak his plans to the press if they were revealed.

By then, McClellan had formed a thoroughly negative opinion of the President and the entire Administration. "I can't tell you how disgusted I am becoming with these wretched politicians,” he wrote to his wife, adding several denunciations of the Cabinet members that culminated with an attack on Lincoln himself as “nothing more than a well meaning baboon . . . 'the original gorilla.'” Nonetheless, and as a response to Lincoln’s special orders, McClellan finally submitted a memorandum detailing his plans for the campaign for Washington. McClellan advocated for loading the Army of the Susquehanna into ships and then going up the Potomac to Washington, thus bypassing Johnston’s supposed impenetrable defenses and many small streams. This would, he argued, break the ineffective and costly pattern McDowell had established of advancing a few miles, fighting a bloody battle, and then setting to rest for months until the Army was ready to do it again.

More than anything, the plan revealed McClellan’s aversion to a decisive battle and the fact that he still considered the war to be one of maneuver, where the capture of enemy cities mattered more than beating enemy armies. Indeed, McClellan believed that the Union could not destroy the Confederate Army outright, and even if it did, taking Washington would take many months of “difficult and tedious” marches, and then going to Richmond would take many more. Capturing Washington, and ostensibly then Richmond, through McClellan’s plan would save thousands of lives and protect Virginia and Maryland from destruction, thus leaving open the possibility for peaceful settlement and the restauration of the Union as it was. In a climate where Radical Republicanism seemed ascendant, these goals were dear to McClellan’s heart. The plan also had the added benefit of providing a “perfectly safe retreat” should the Army of the Susquehanna be bested by the rebels.

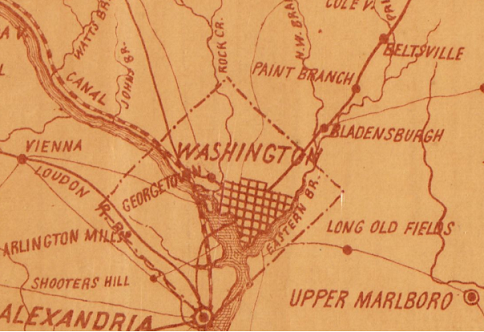

But political and military realities were against McClellan. Lincoln favored an advance along the railroad to Washington. It was true that it was perpendicular to several small rivieres, but Beltsville, the headquarters of the Army of the Susquehanna, was only 12 miles away from Washington, and the railroad provided an easy path for invasion, supply, and, if absolutely necessary, retreat. Halleck and Stanton both favored Lincoln’s plan, the greatest benefit being that a successful battle would end with the Confederates with their backs to the Potomac, thus assuring their destruction. Moreover, McClellan plan would leave nothing but a few regiments between the Confederates and Baltimore, thus presumably they would be able to strike against the North. This quick, aggressive campaign against Washington would cripple the rebels, retake Washington, and force what remained of the Confederate Army to Richmond, thus completely liberating Maryland.

This plan was also more practicable because the railroad provided easy transportation. Daniel McCallum, superintendent of the U.S. Military Rail Roads, is to thank for this. This organization had been established by Stanton in order to execute the Congressional provisions that allowed the President to take over any railroad “when in his judgment the public safety may require it.” In the North, Stanton mostly used this as a way to coerce Northern railroads into providing fair rates and priority for the military. But in the occupied South, “the government went into the railroad business on a large scale”, starting on January 1862, when Congress approved the Act. The U.S.M.R.R. took over many railroads, built miles more, and maintained them against rebel raids. In Maryland, the maintenance of the Washington Railroad was tasked to Herman Haupt, the “war’s wizard of railroading.”

Herman Haupt

Similar to Stanton in his brusque but extremely capable personality, Haupt brought order out of the chaos of Virginia’s and Maryland’s railroads, but his greatest achievement was his capacity to rebuild destroyed rails in record time. His corps of engineers was able to “build bridges quicker than the Rebs can burn them down”, and even when he lacked material and human resources, Haupt was able to create wonders, such as building a rail with green logs with inexperienced soldiers in less than two weeks. Lincoln was so awed that he pronounced it “the most remarkable structure that human eyes ever rested upon. That man, Haupt, has built a bridge . . . over which loaded trains are running every hour, and upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks." As in other areas of the war, the logistical power and human talent of the Union overwhelmed the poor capacity of the rebels. Soon enough, Haupt had rebuilt all the railroads and bridges the rebels had burned in their retreat, and the Washington railroad became a solid route for the next campaign.

With that in mind, Lincoln then pointed out that McClellan’s plan would “involve a greatly larger expenditure of time, and money, than mine”, and under the political circumstances of the time, the Union could afford neither. The sinews of war must be considered separately; suffice it to say that the Union was in a bad economic shape because the war seemed to have no end in sight and this eroded the confidence of investors in bonds and the finances of the Treasury. Time was a more pressing matter. After more than a year, the capital and Harpers Ferry both remained in the hands of the enemy, and that constituted a constant humiliation for the nation in general and the Administration in special. If the rebels in Washington were driven away, the ones in Harpers Ferry could hardly make a stand, and both groups would be forced to retreat. But although both places had a high value, strategic, significative and political, for Lincoln the most important objective was destroying the enemy forces.

Refusing to defer to the supposed professionals any longer, Lincoln overrode McClellan and ordered that his plan for a direct attack on Washington be carried out. However, Lincoln wished to still cooperate with McClellan, and thus, to both soother the General’s ego and provide a blueprint for future operations, they settled on a direct attack against Washington first, and then an amphibious operation against Richmond. The Richmond Plan was markedly similar. It entailed loading up the Army into boats and steaming up the York River to the town of West Point, Virginia, under 40 miles away from the Confederate capital. In truth, Lincoln was also skeptical about the York Plan, but he recognized that if he refused to go along, McClellan would resign, thus resulting in “fatal demoralization within our ranks and, perhaps more fatally, further delay.” It seems that Lincoln also acquiesced because he had no one with whom he could replace McClellan.

The Committee on the Conduct of War recommended their new darling, Frémont, but his military failure and political blunders had tarnished his reputation. At one point, Lincoln summoned the 63-year-old Ethan Allen Hitchcock, grandson of the Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, to Philadelphia, to inquire if he wanted to replace McClellan as commander of the Army of the Susquehanna. Hitchcock had served with distinction for many years until a spat with Jefferson Davis, who served as Secretary of War then of US and now of the Confederacy, made him resign. Though Hitchcock said he “felt positively sick” about McClellan’s actions, he declined the command on the grounds of his age and health. No other options presented themselves – Grant, the only general who had achieved actual victories, was busy in Corinth; Burnside was working with Farragut to take New Orleans; and though Lincoln considered bringing John Pope to Maryland as a way to export Western puck, he ultimately decided against it because Pope hadn’t distinguished himself yet.

Lincoln, however, did heed the Committee’s recommendation to reorganize the Army of the Susquehanna into four corps. Previously, there were 9 divisions that had reported directly to McDowell, and the Annapolis Corps, under McClellan. Now, all 12 divisions answered directly to McClellan, and most of them were now staffed with his supporters. Lincoln and many others were offended by “McClellan’s purge”, which aside from disrespecting McDowell’s memory, had filled the ranks with former Democrats and Chesnuts. Perhaps this was inevitable – since the Democrats had dominated Congress, the great majority of West Point recruits were Democratic in allegiance. But amidst rumors that McClellan actually didn’t intend to crush the rebellion and whispers of traitors within the Army, reorganization was urgently needed. Most of the generals who would become corps commanders under the new scheme would be Republicans as well, though this was because of their seniority, rather than their partisan inclinations.

John Pope

Consequently, Lincoln issued an order reorganizing the Army of the Susquehanna into four corps. To protect his “left political flank”, he also brought Frémont to command a new Army in Kanawha. Though McClellan fumed about these decisions, the important fact was that the York Plan had been approved, and thus he suddenly changed his tune and now declared that “The President is all right—he is my strongest friend.” The plan, in McClellan’s mind, would result in a crushing victory over the rebels, by forcing them to abandon their defenses and fight in the terrain McClellan had chosen. Its success was “as certain by all the chances of war”, and it would result in the evacuation of Virginia, Tennessee and North Carolina. Then a Union juggernaut would be able to advance into the Deep South. But first, Washington had to be liberated.

The task of preventing this fell on the shoulders of Joseph E. Johnston. Now that Beauregard had been removed, Johnston was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Confederate success at repealing Union attacks at Corinth and New Orleans had imbued sullen Southerners with renewed hope, however, as in the North, the Virginia theater obtained the lion’s share of public attention. The Confederate prospects still seemed bleak, and Johnston, who like McClellan feared a failure that would destroy his reputation, seemed ready to give up Washington and retreat to Richmond. The decision, Breckinridge conceded, was militarily sound, but coming after many reverses it would be politically disastrous. Robert E. Lee, who Breckinridge had brought as a military adviser, and Secretary of War Davis concurred, and the President ordered Johnston to defend Washington with all the means at his disposal.

Yet, all the Confederate leaders recognized their present weakness. “Events have cast on our arms and our hopes the gloomiest shadows,” wrote Davis, and Breckenridge tended to agree. Decided to prevent the destruction of his army and his Confederacy, Breckenridge made careful preparations to allow Johnston to safely retreat should the situation turn for the worse – thus, preventing the army from being driven with their backs to the Potomac as Lincoln wanted. But, as already detailed, Breckinridge’s confidence of Johnston had suffered. That’s why Lee had been brought to Richmond. Deploring the “politicians, newspapers, and uneducated officers” who had denigrated Lee for “failing at a task that no man could have succeeded at”, Breckenridge expressed his faith in Lee. Davis’ opinion mattered a lot as well, since, unlike Beauregard or Johnston, Davis trusted Lee.

In March, 1862, Breckinridge relieved Johnston of his position as General in-chief, writing the General that this decision “does not reflect any lack of confidence in you, or express any waning of the warm sentiments with which the country and I regard you,” but was rather a measure designed to allow Johnston to “concentrate on the defense of our territory, and carry our arms to further victories.” For the moment, Johnston, who had always wanted to take field command of the main Confederate army, was gratified enough that he did not raise any protest. Lee was not promoted to the position, partly because Breckinridge wanted to test him first, and also due to political problems within the Confederate Congress.

Indeed, in 1862 Congress had submitted a bill to define more clearly the office of General in-chief. The title was borrowed from its US equivalent, and Breckinridge had created it because he believed he needed someone to oversee Confederate mobilization, but it was not defined by law. In order to grant the position more power, Breckinridge had pushed for a bill, but his enemies in Congress amended it and also combined it with the bill that would grant Beauregard the rank of Confederate Marshal. The resulting bill would not only allow the General in-chief to take command of any army without the President’s authorization, but it would also estipulate that Beauregard would be superior to the General in-chief by virtue of his new rank. Breckenridge could not accept such a bill, and when the Congress passed it, he vetoed it.

Joseph E. Brown

The debacle contributed to the polarization of the Confederate Congress, and indeed the Confederacy as a whole, into two distinct political parties: a pro-administration one, that came to be known as Nationalists, and an anti-administration one, who called themselves the Constitutionalists but quickly came to be denigrated as Reconstructionists or Tories. At first, Confederates had gloried on their lack of formal political parties. This was because by 1860 the South had effectively become a one-party region under the complete control of the Democrats, and also the need to create a united front for secession. Thus, the members of the First Congress were congratulated because "the spirit of party has never shown itself for an instant in your deliberations." But Breckenridge recognized that political parties were a way to channel support from the public for his policies and invoke the whip of Party discipline in order to make politicians fall in line.

Coming from one of the few states where other parties retained strength, mainly the Constitutional Union as a form of revived Whiggery, Breckinridge believed that in order to lend vitality to his administration and defeat enemies who opposed him due to factional or personal reasons, he needed to create an effective political party. Many months more would pass before Breckinridge formally created the National Party, but signs of change abounded, as he started to exercise his patronage powers to fill the ranks of the Army and the Bureaucracy with his supporters. The fact that he had been the 1860 Presidential candidate helped, for the die-hard supporters who had campaigned for him were eager to return to the fray. “Those who, merely for spite or for the callous expectation of political advantage, attack our beloved President shall receive no mercy or charity from us,” declared one of these loyalists.

Breckinridge was careful not to antagonize those that opposed his policies, and the fact that he could not run for reelection once his six-year term expired probably prevented the full realization of a partisan system, but Breckinridge had by then started to rally supporters around himself in a pro-war, pro-administration, pro-centralized power Party. The Nationalists attracted mostly those who felt strong patriotism for the Confederate cause, such as Robert E. Lee, and those who realized the need of “centralized, decisive action . . . in the face of armies vastly superior in numbers”, like Davis or Senator Louis Wigfall. The Nationalists were, for the most part, stalwart Democrats, and though they ranged from moderates like Breckinridge to fire-eaters, most shared a common commitment to achieving Confederate independence by all means necessary, even if it was necessary to violate States Rights or civil liberties.

The first test of this new Party was a second vote for the General in-chief bill. This time, Breckinridge brought patronage and the expectation of future favors to bear. The President’s methods were denounced as “profoundly corrupt . . . a bad faith effort to compel politicians to betray their constituents and their country, yielding our rights for some loaves and fishes”. But they bore results, and the final bill created a General in-chief position that was completely subordinate to the President, ascended Beauregard to Marshal but made the rank completely symbolical, and included a highly suggestive passage regarding the war powers of the President: “the Chief Executive shall have the exclusive power to command the armies of the Confederate States, and shall be able to take any action he may regard as necessary for the public good, the welfare of the people, and the successful prosecution of the war.”

This outraged the President’s opponents. Former Whigs formed the greatest basis of opposition. After the Whig Party had died in 1854, most Whigs had turned towards the Democrats in order to protect slavery and States Rights, but many of them found it hard to completely relinquish their former allegiance, and wanted compromise and moderation. The myth of the moderate Southern Whig would plague the Republican Party and its efforts at Reconstruction, since they were as committed to Confederate independence, white supremacy and slavery as their opponents. Their main division was over methods, not goals, and they consistently opposed the Administration and its efforts to centralize power for the effective prosecution of the war. The most bitter opposition was aroused over the Conscription Act.

The Confederate States Congress

The Confederate Armies were running out of men due to the rigors of war, and the simple fact that it did not seem to be such a glorious enterprise anymore. After Lincoln’s first volunteer call had been for three years of service, Breckinridge had pushed for a law extending the service of the first Confederate volunteers, who had only enlisted for a year. At first, the Congress rejected this solution and instead tried to entice men to reenlist by granting then bounties, a 60-day furlough, and the right to form new regiments and choose new officers. Breckinridge quickly realized just how terrible the law could be, declaring that “any Yankee law would be hardly worse for the morale of our armies and the welfare of our country”. Indeed, furloughs would weaken the army just as much, and allowing for the creation of new regiments would result in fatal disorganization. Lee, too, declared it “highly disastrous”, and proposed a draft instead. Davis at first considered that extending the service would be a breach of contract, but he came around as well. Thus, in September 1861, in the immediate aftermath of Baltimore, the Confederate Congress extended the service of the one-year volunteers.

But by April 1862, Breckinridge had become convinced that a stronger measure was needed. On April 11th, 1862, Breckinridge sent a message to Congress asking for the conscription of all able white men, between 18 and 35, for three-years of service. More than two thirds of the Congressmen voted in favor of the first Conscription law in American history, though many advocates of States Rights cried out against the measure. For example, Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia denounced it as a “dangerous usurpation by Congress of the reserved rights of the States” that was “at war with all the principles for which Georgia entered into the revolution.” A soldier called it “so gross a usurpation of authority . . . [that it] would go far to make me renounce my allegiance", and a comrade agree that "when we hear men comparing the despotism of the Confederacy with that of the Lincoln government—something must be wrong”. Yet, Breckinridge considered it essential for Confederate survival, especially when McClellan finally moved forward on June 22nd, 1862.

As proposed by Lincoln, the plan called for an advance from Beltsville to Washington. Johnston decided to make a stand in the Anacostia River, in a part where this tributary of the Potomac forked into two branches. The river ran towards Washington, thus providing an easy venue for invasion. Entrenchment behind the West Branch of the Anacostia seemed the Confederates’ only hope. As it in other battles of the war, the Federals and the Rebels know the ensuing battle with different names – Anacostia for the Union, Bladensburg for the Confederacy. As he often did, McClellan issued a Napoleonic declaration, hoping to boast the morale of the soldiers who idolized him. “For a long time I have kept you inactive,” he said, “but not without purpose; you were to be disciplined, armed and instructed . . . A manly fight on the decisive battlefield is ahead of us, but I shall watch over you, as a parent over his children . . . I know I can trust you to save our country, and, if necessary, follow me to our graves, for our righteous cause.”

Against McClellan’s 120,000 Federals, Johnston was able to field near 70,000 men. Unbeknownst to the Yankees, Harpers Ferry had only a small skeleton force. Instead of attacking immediately, McClellan stopped in Bladensburg and gathered his forces for a well-calculated assault the next day. Since the battlefield was an area of woods with several small lagoons, the main assault would have to go through the bridge of the Washington Railroad – a structure that would be immortalized as the Bloody Bridge. Rebels had, of course, destroyed the original bridge, but Union engineers had built a replacement in record time, without being harassed by Johnston, who thought an attack imminent. Two of the corps were to cross the bridge, while a corps in the Union left was going to try to ford the river in a less woody area. Even if it failed, it would be able to create a distraction, thus sowing doubt and disorganization within the rebel ranks. A corps was held back in reserve, to exploit any breakthrough. Though McClellan was still under the delusion that Confederate numbers matched his at the very least, he expected that General Fitz John Porter, his protégé and the one tasked with spearheading the attack, would be able to roll up the Confederate defenses. After some preparation, the attack started early on the morning of June 25th.

The theater of operations

But instead of all corps going forward on a massive attack, McClellan launched the attacks on three stages, one corps after the other. Fortunately for the Federals, the battles were “phenomenally mismanaged” by Johnston. For one, he was unable to see the talents of Stonewall Jackson, who, despite the fame he had acquired for his highly mobile campaign during Second Maryland, was once again relegated to defense, a role that ill-suited the Virginian. Second, he also launched his attacks in piecemeal style. Johnston did achieve a small success by sending troops to ford the river on the Confederate right, a feat they could achieve because they were guided by scouts who knew the territory well. But Yankees under the command of Edwin “Bull” Sumner were able to drive them back, though McClellan, cautious as ever, kept Sumner from fording the river as well to follow up his attack.

The fighting around the Anacostia was some of the harshest in the war. Most of the men were forced to fight “in small clusters amid thick woods and flooded clearings”. If they fell wounded, they had to be propped up against fences or stumps, because otherwise they would sink deep into the mud. Soldiers, both Confederate and Union, fought desperately. Despite how editors and generals proclaimed that the army was “eager to be led against the enemy”, most soldiers admitted that they were actually terrified, and what kept them in their lines was the “moral fear of turning back”, and the painful awareness that they would be betraying their comrades. Thus, and despite their fears, regiments did not falter and went forward as ordered, and suddenly “the whole landscape for an instant turned slightly red”. This kind of “fighting madness” allowed the soldiers to fight on despite their fears. "The men are loading and firing with demonaical fury and shouting and laughing hysterically," wrote a Union officers many years later, undoubtedly remembering the images of Anacostia vividly.

The following day, the most brutal scenes of battle took place in the Bloody Bridge, where the corps of Porter and Joseph Hooker, an egotistical and aggressive man who would earn the sobriquet of Fighting Joe that day, attacked the forces of Stonewall Jackson and A. P. Hill. Convinced that no attack would take place in Harpers Ferry, the few divisions there were ordered to Anacostia, while Jeb Stuart, who had dazzled McDowell at Second Maryland, started another daring action in McClellan’s rear. For many difficult and horrifying hours, the Blue and the Gray contested the bridge. “At the end of the day,” said the young captain of the 20th Massachusetts, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., “the river was running red with our blood.” With neither commander willing to try to ford the river elsewhere, conquering the bridge became indispensable.

Finally, after the bloodiest day in American history, broken Confederate brigades fell back to Washington. Superior Union numbers and the relentless assault of the Yankee commanders resulted in heavy casualties for the Confederates, who, one observed said, “had gone down as the grass falls before the scythe”. But McClellan was shaken by the carnage, and he decided against sending General William B. Franklin’s corps to finish the job. McClellan apparently believed that Johnston held infinite reserves back for some reason, and that if he crossed the Anacostia and attacked, those hidden rebel legions would surge and finish him instead. Thus, he decided to prepare for another attack.

The final day of the battle, June 27th, Hooker attacked and managed to drive back the greybacks and establish a bridgehead on the other side. Now the Union troops were well position to launch a final, massive thrust that would drive the Confederates to the Potomac, where their destruction could be assured. A well-executed maneuver could even cut the only fords over the Potomac, thus trapping the rebels. But after two days of heavy fighting, Hooker’s divisions were unable to continue. McClellan was about to send in Porter’s corps, which had had time to rest, but then Porter shook his head. "Remember, General," Porter said, "I command the last reserve of the last army of the Republic.” McClellan did not renew the assault, and despite the arrival of new reinforcements, he did nothing to help Hooker when a sudden Confederate counterattack started and saved the Confederate center from disintegration.

Joseph Hooker

Finally, night fell. The casualties were actually less than those of Second Maryland: 15,000 in the Confederate side, and 14,000 in the Union side. The combined total of fatalities from both armies was around 8,000. Losses of more than 50% were reported on several Southern regiments, and there was little hope of being able to counterattack. Realizing that any concentrated Union assault could probably destroy them, the rebels yielded to the inevitable, and during the night they evacuated their positions and retreated several miles to the Manassas Junction, near another small stream named Bull Run. Breckenridge’s magnificient organization allowed them to retreat without losing any of the supplies that the Confederacy could ill-afford. McClellan feebly tried to pursuit, but Jeb Stuart was able to easily hold him at bay. The rebel army had, once again, escaped to fight another day. But the facts were clear – Washington was now in Union hands.

“Maryland is entirely freed from the presence of the enemy, who has been driven across the Potomac,” McClellan wired to Philadelphia. “The National Capital has been retaken by our arms.” This was the victory the Northern people had waited for, and, after a year, Washington was finally liberated from the “odious presence of the slaveholder crew.” Declaring that “Waterloo is eclipsed”, the people celebrated jubilantly. A crowd of serenaders approached Lincoln in Philadelphia, and the President declared with just pride that the “gigantic Rebellion”, made to overthrow the principle that “all men are created equal” was dealt a hard blow.

In hindsight, the Battle of Anacostia doesn’t seem like a giant success, mainly because McClellan failed to pursue Johnston across the Potomac and actually dealt the final blow to the Rebellion as he had promised. He had only intended to “drive the enemy from our soil”, which made Lincoln exclaim that “the whole country is our soil”. Indeed, the strategic effect of Anacostia seems to be low, since the Confederate army was still intact and able, and there were still many miles and many rivers between the Army of the Susquehanna and Richmond. McClellan wanted to execute the York Plan, which promised to capture Richmond quickly, but the preparations for the plan definitely would not be quick. Furthermore, Anacostia only reinforced McClellan’s arrogance, and this meant that when he launched his next campaign he was completely assured of his own success, a hubris that would lead the Union to disaster.

Battle of Anacostia

Still, the liberation of Washington was of extremely symbolic and sentimental importance, and it had far reaching effects for the entire war. On the Confederate side, Breckinridge finally had had enough. The President dismissed Johnston and appointed Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, and he also brought James Longstreet from North Carolina to Richmond. The most important development, however, is that Lincoln finally issued the Emancipation Proclamation. After he “fixed it up a little”, Lincoln called for the cabinet to hear it on July 1st. Once again, he read from a comedy book, before turning to business. “I think the time has come now,” he told them, “the recent successes of our arms must be followed up with this strike against the South’s pillar of strength. This is the weapon through which we will end the rebellion.”

In the Fourth of July, 1862, Lincoln entered Washington for the first time since April 19th, 1861, when he had been forced to flee the city. Only charred ruins remained, but hundreds of contrabands and many cheering Maryland Unionists gathered to receive the President. In front of the fallen White House, Lincoln announced that, in order to “end this great Civil War” and “bring back the insurgent states under the authority of the National government”, he declared that “all persons held as slaves” within any state or part of a state still in rebellion would be “then, thenceforward, and forever free,” effective July 4th, 1862. Thus, by this ”act of justice”, described as a “fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion”, Lincoln transformed the war into one for Union and Liberty.

McClellan promptly launched into a winded speech about the art of war and the necessity of supply lines and evacuation routes. After he finished, Wade simply told him that what the people wanted and needed was “a short and decisive campaign”. McClellan then left, and although he told a friend that Wade had been courteous and that the Committee was “anxious to sustain him, and to cooperate”, the reality was other. Indeed, after Wade asked him what he thought of the “science of generalship”, Chandler frankly admitted that he did not know much, “but it seems to me that this is infernal, unmitigated cowardice”.

Lincoln probably agreed. The months between March and June, 1862 represented his low point as commander in chief. During these months, the only major Union actions ended in defeat: Grant failed to take Corinth, Farragut to take New Orleans, and both Buell and McClellan refused to act. The Emancipation Proclamation remained in a drawer. His messages to his generals reflect Lincoln’s profound discouragement. He practically begged Buell to move into East Tennessee, where “our friends . . . are being hanged and driven to despair, and even now, I fear, are thinking of taking rebel arms for personal protection. In this we lose the most valuable stake we have in the South.” Buell’s failure to do so “disappoints and distresses me”. Grant also had to deal with a barrage of criticism following the Battle of Corinth, and a weary Lincoln seemed less eager to defend him.

Nonetheless, the greatest sign of Lincoln’s despairing mood is his comment to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. “General, what shall I do?”, the President said, “The people are impatient; Chase has no money… No general will act. The bottom is out of the tub. What shall I do?” Indeed, what should he do? McClellan, again showing his timid behavior, perhaps afraid of tarnishing his reputation by defeat, refused to move until meticulous preparations were set in place. This earned the ire of Congressional Republicans, who had hoped that McClellan could live up to his vainglorious promises and, as a Radical newspaper had once predicted, “infuse vigor, system, honesty, and fight into the service.” But the image of McClellan as God’s instrument to save the Union, which partially appeared as a reaction to McDowell’s supposed slowness, was crumbling away.

Republicans had once expressed similar impatience with McDowell, but the fallen general’s delay was often well-founded, and though neither of his campaigns were spectacular successes per se, he had achieved something, retaking Baltimore and setting the stage for a campaign for Washington. But McClellan seemed to simply differ, always asking for more troops and expressing fears of secret rebel legions. " 'Young Napoleon' is going down as fast as he went up," observed an Indiana Republican, and indeed, people who had once supported McClellan now vilified him. A bitter press started to assail him more harshly as well. Perhaps the most damaging fact was that McClellan’s relationship with the Administration was now strained.

In special, Secretary of War Stanton and McClellan quickly grew to detest each other. Stanton was growing closer to the Radical Republicans, and he shared their vision of McClellan as a coward and wanted the war to be pursued with more vigor. “We have had no war. We have not even been playing war . . . this army has got to fight or run away . . . the champagne and oysters on Havre de Grace must be stopped”, he declared. Whereas McClellan had at first been delighted with Stanton’s appointment, saying it was “a most unexpected piece of good fortune”, now he denounced Stanton as “without exception the vilest man I ever knew”, a traitor “willing to sacrifice the country & its army for personal spite, allied with abolitionist hell hounds.”

Zachariah Chandler

McClellan’s relationship with the President was also deteriorating. At first Lincoln was willing to give McClellan an opportunity. When the General asked that the President protect him from public pressure that would “push me and this noble army into hasty and disastrous action,” Lincoln assured him that McClellan would have his support, though he added that the demands of Republican politicians were "a reality, and must be taken into account”. But soon enough, Lincoln was convinced that he needed to “take these army matters in his own hands”. The main factors behind this were the fact that Lincoln’s confidence on professional military men had been eroded, thus he was more willing to assert himself, and also that he did not believe McClellan’s reports of Confederate numbers anymore, which was mostly due to the Annapolis disaster.

The opinion of the Committee of War, which declared that the Commander in chief “must, by law, command” and not continue “this injurious deference to subordinates”, spurned Lincoln into action. Saying that he “would like to borrow the Army of the Susquehanna, if General McClellan would not use it”, Lincoln drafted Special Orders No1 and No2 on April 2nd. These orders called on the “Land and Naval forces” to move against the “insurgent armies” before or on June 14th – the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Lincoln then summoned McClellan to an informal council of war, and inquired for his plans of action against the rebel army. Sullen and almost insubordinate because he felt attacked, McClellan simply declared that “the case was so clear a blind man could see it”, and, he whispered to Meigs, he feared Lincoln would leak his plans to the press if they were revealed.

By then, McClellan had formed a thoroughly negative opinion of the President and the entire Administration. "I can't tell you how disgusted I am becoming with these wretched politicians,” he wrote to his wife, adding several denunciations of the Cabinet members that culminated with an attack on Lincoln himself as “nothing more than a well meaning baboon . . . 'the original gorilla.'” Nonetheless, and as a response to Lincoln’s special orders, McClellan finally submitted a memorandum detailing his plans for the campaign for Washington. McClellan advocated for loading the Army of the Susquehanna into ships and then going up the Potomac to Washington, thus bypassing Johnston’s supposed impenetrable defenses and many small streams. This would, he argued, break the ineffective and costly pattern McDowell had established of advancing a few miles, fighting a bloody battle, and then setting to rest for months until the Army was ready to do it again.

More than anything, the plan revealed McClellan’s aversion to a decisive battle and the fact that he still considered the war to be one of maneuver, where the capture of enemy cities mattered more than beating enemy armies. Indeed, McClellan believed that the Union could not destroy the Confederate Army outright, and even if it did, taking Washington would take many months of “difficult and tedious” marches, and then going to Richmond would take many more. Capturing Washington, and ostensibly then Richmond, through McClellan’s plan would save thousands of lives and protect Virginia and Maryland from destruction, thus leaving open the possibility for peaceful settlement and the restauration of the Union as it was. In a climate where Radical Republicanism seemed ascendant, these goals were dear to McClellan’s heart. The plan also had the added benefit of providing a “perfectly safe retreat” should the Army of the Susquehanna be bested by the rebels.

But political and military realities were against McClellan. Lincoln favored an advance along the railroad to Washington. It was true that it was perpendicular to several small rivieres, but Beltsville, the headquarters of the Army of the Susquehanna, was only 12 miles away from Washington, and the railroad provided an easy path for invasion, supply, and, if absolutely necessary, retreat. Halleck and Stanton both favored Lincoln’s plan, the greatest benefit being that a successful battle would end with the Confederates with their backs to the Potomac, thus assuring their destruction. Moreover, McClellan plan would leave nothing but a few regiments between the Confederates and Baltimore, thus presumably they would be able to strike against the North. This quick, aggressive campaign against Washington would cripple the rebels, retake Washington, and force what remained of the Confederate Army to Richmond, thus completely liberating Maryland.

This plan was also more practicable because the railroad provided easy transportation. Daniel McCallum, superintendent of the U.S. Military Rail Roads, is to thank for this. This organization had been established by Stanton in order to execute the Congressional provisions that allowed the President to take over any railroad “when in his judgment the public safety may require it.” In the North, Stanton mostly used this as a way to coerce Northern railroads into providing fair rates and priority for the military. But in the occupied South, “the government went into the railroad business on a large scale”, starting on January 1862, when Congress approved the Act. The U.S.M.R.R. took over many railroads, built miles more, and maintained them against rebel raids. In Maryland, the maintenance of the Washington Railroad was tasked to Herman Haupt, the “war’s wizard of railroading.”

Herman Haupt

Similar to Stanton in his brusque but extremely capable personality, Haupt brought order out of the chaos of Virginia’s and Maryland’s railroads, but his greatest achievement was his capacity to rebuild destroyed rails in record time. His corps of engineers was able to “build bridges quicker than the Rebs can burn them down”, and even when he lacked material and human resources, Haupt was able to create wonders, such as building a rail with green logs with inexperienced soldiers in less than two weeks. Lincoln was so awed that he pronounced it “the most remarkable structure that human eyes ever rested upon. That man, Haupt, has built a bridge . . . over which loaded trains are running every hour, and upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks." As in other areas of the war, the logistical power and human talent of the Union overwhelmed the poor capacity of the rebels. Soon enough, Haupt had rebuilt all the railroads and bridges the rebels had burned in their retreat, and the Washington railroad became a solid route for the next campaign.

With that in mind, Lincoln then pointed out that McClellan’s plan would “involve a greatly larger expenditure of time, and money, than mine”, and under the political circumstances of the time, the Union could afford neither. The sinews of war must be considered separately; suffice it to say that the Union was in a bad economic shape because the war seemed to have no end in sight and this eroded the confidence of investors in bonds and the finances of the Treasury. Time was a more pressing matter. After more than a year, the capital and Harpers Ferry both remained in the hands of the enemy, and that constituted a constant humiliation for the nation in general and the Administration in special. If the rebels in Washington were driven away, the ones in Harpers Ferry could hardly make a stand, and both groups would be forced to retreat. But although both places had a high value, strategic, significative and political, for Lincoln the most important objective was destroying the enemy forces.

Refusing to defer to the supposed professionals any longer, Lincoln overrode McClellan and ordered that his plan for a direct attack on Washington be carried out. However, Lincoln wished to still cooperate with McClellan, and thus, to both soother the General’s ego and provide a blueprint for future operations, they settled on a direct attack against Washington first, and then an amphibious operation against Richmond. The Richmond Plan was markedly similar. It entailed loading up the Army into boats and steaming up the York River to the town of West Point, Virginia, under 40 miles away from the Confederate capital. In truth, Lincoln was also skeptical about the York Plan, but he recognized that if he refused to go along, McClellan would resign, thus resulting in “fatal demoralization within our ranks and, perhaps more fatally, further delay.” It seems that Lincoln also acquiesced because he had no one with whom he could replace McClellan.

The Committee on the Conduct of War recommended their new darling, Frémont, but his military failure and political blunders had tarnished his reputation. At one point, Lincoln summoned the 63-year-old Ethan Allen Hitchcock, grandson of the Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, to Philadelphia, to inquire if he wanted to replace McClellan as commander of the Army of the Susquehanna. Hitchcock had served with distinction for many years until a spat with Jefferson Davis, who served as Secretary of War then of US and now of the Confederacy, made him resign. Though Hitchcock said he “felt positively sick” about McClellan’s actions, he declined the command on the grounds of his age and health. No other options presented themselves – Grant, the only general who had achieved actual victories, was busy in Corinth; Burnside was working with Farragut to take New Orleans; and though Lincoln considered bringing John Pope to Maryland as a way to export Western puck, he ultimately decided against it because Pope hadn’t distinguished himself yet.

Lincoln, however, did heed the Committee’s recommendation to reorganize the Army of the Susquehanna into four corps. Previously, there were 9 divisions that had reported directly to McDowell, and the Annapolis Corps, under McClellan. Now, all 12 divisions answered directly to McClellan, and most of them were now staffed with his supporters. Lincoln and many others were offended by “McClellan’s purge”, which aside from disrespecting McDowell’s memory, had filled the ranks with former Democrats and Chesnuts. Perhaps this was inevitable – since the Democrats had dominated Congress, the great majority of West Point recruits were Democratic in allegiance. But amidst rumors that McClellan actually didn’t intend to crush the rebellion and whispers of traitors within the Army, reorganization was urgently needed. Most of the generals who would become corps commanders under the new scheme would be Republicans as well, though this was because of their seniority, rather than their partisan inclinations.

John Pope

Consequently, Lincoln issued an order reorganizing the Army of the Susquehanna into four corps. To protect his “left political flank”, he also brought Frémont to command a new Army in Kanawha. Though McClellan fumed about these decisions, the important fact was that the York Plan had been approved, and thus he suddenly changed his tune and now declared that “The President is all right—he is my strongest friend.” The plan, in McClellan’s mind, would result in a crushing victory over the rebels, by forcing them to abandon their defenses and fight in the terrain McClellan had chosen. Its success was “as certain by all the chances of war”, and it would result in the evacuation of Virginia, Tennessee and North Carolina. Then a Union juggernaut would be able to advance into the Deep South. But first, Washington had to be liberated.