You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Mexican Century: An Alternate Mexican History

- Thread starter AlexGarcia

- Start date

Until now (1815-1816), yes, it's pretty much the same, in part because the events in New Spain didn't affect fundamentally the other wars. Now, since Mexico is finally (de facto) independent, the balance in the region has shifted to the disadvantage of Spain, which means such wars are going to last less time. My intention is for Mexico to help in a way the efforts of other insurgents, especially the Colombian ones (since they are the closest ones to Mexican territory). Mexico's influence could also change some aspects of the South American nascent politics, but I still need to define how much.How the Wars of Independence are going in South America? Pretty much like OTL?

I already mentioned above some hints about how Northern colonization and who will be the ones who migrate to Texas, for example. Now, for the case of the Californian Gold Rush, I haven't defined if it's possible for Mexico to discover the Californian gold fields earlier or not, especially because the territories where such fields were located OTL are not yet controlled by Mexico.The status of the settlement/colonization of the Northern territories. Maybe earlier California gold rush?

San Martin's campaign to Chile likely is still happening since he has already planned and will end as a success just like OTL. Things will definitely get interesting when the war reaches Peru.Until now (1815-1816), yes, it's pretty much the same, in part because the events in New Spain didn't affect fundamentally the other wars. Now, since Mexico is finally (de facto) independent, the balance in the region has shifted to the disadvantage of Spain, which means such wars are going to last less time. My intention is for Mexico to help in a way the efforts of other insurgents, especially the Colombian ones (since they are the closest ones to Mexican territory). Mexico's influence could also change some aspects of the South American nascent politics, but I still need to define how much.

Yeah feel like Spain is going to triple down on trying to keep Peru as it’s the only place that was fairly royalist and also served as their second biggest crown jewel after MexicoSan Martin's campaign to Chile likely is still happening since he has already planned and will end as a success just like OTL. Things will definitely get interesting when the war reaches Peru.

Based if Mexico would essentially become the hegemon of the western hemisphere!Until now (1815-1816), yes, it's pretty much the same, in part because the events in New Spain didn't affect fundamentally the other wars. Now, since Mexico is finally (de facto) independent, the balance in the region has shifted to the disadvantage of Spain, which means such wars are going to last less time. My intention is for Mexico to help in a way the efforts of other insurgents, especially the Colombian ones (since they are the closest ones to Mexican territory). Mexico's influence could also change some aspects of the South American nascent politics, but I still need to define how much.

Remember when I made a whole Constitution using the OTL Constitution of Apatzingán as a basis (along with the French Constitution of Year I and the Cadiz Constitution)?

Well, I'm at the verge of finishing the "rework" of the Constitution: let's formalize it as the Articles of Incorporation and amendments of 1816-17.

(Agony, please help me)

The new update will include a link to access the reworked Constitution in its totality!

Well, I'm at the verge of finishing the "rework" of the Constitution: let's formalize it as the Articles of Incorporation and amendments of 1816-17.

(Agony, please help me)

The new update will include a link to access the reworked Constitution in its totality!

Two things:

1. The new update is being produced finally: I ended the Constitutional modifications (at least generally, maybe I will change some specific details if necessary);

2. RIP to a real one, farewell Mr. Toriyama. Today is a sad day for people like me, who truly love Dragon Ball.

1. The new update is being produced finally: I ended the Constitutional modifications (at least generally, maybe I will change some specific details if necessary);

2. RIP to a real one, farewell Mr. Toriyama. Today is a sad day for people like me, who truly love Dragon Ball.

The Constitution of 1817

Excerpts from "Historia Mínima Constitucional de México [Minimal Constitutional History of Mexico], 3rd edition", 2016.

The unification of Central America with Mexico only meant the first step in the country's independent history; a history that, by the way, was not exempt from suffering setbacks, as evidenced by the constitutional debates once the Act of Understanding with the Central American representatives was validated. Once the war was over, there was a short period of relative calm known as the honeymoon of Mexican Independence, which ended abruptly once the Mexican Supreme Congress called to translate the agreements with the Central Americans into the Constitution, which led to a whole year of constitutional debates within and outside the Congress, which in some cases almost led to federalist and centralist revolts: the war had been won, but it was necessary to win the peace.

The Constitution of 1813, although quite innovative in terms of individual guarantees (currently human rights) suffered from some problems, the main one being that, after all, it was a provisional constitution, a document that was not meant to last forever. Morelos himself had said before the Plenary of Congress that "this document is unfeasible to adequately manage a country in times of war, much less in times of peace". Other individuals also advocated a structural reform that would not only focus on the federalism-centralism issue, but also on the definition of the national powers and their degree of powers (i.e., the checks and balances of each national power). When the Constituent Congress was installed in Mexico City, all ties of "solidarity" and "fraternity among brothers" were quickly forgotten, and even with the lack of political parties, the Congress quickly became politicized.

Judging by the existing documentation, it seems evident the concern among various politicians of the time to define how they saw the ideal Mexico for themselves and those close to them. People like Carlos María de Bustamante, close to Morelos himself and a fervent Catholic, although in favor of guaranteeing a bill of rights in the Constitution (and expanding it if necessary), opposed both the existence of other faiths in the country and the formation of a federal state in Mexico [1], since "the history of our Nation, from the Anahuac Empire of the Aztecs to the Spanish Viceroyalty, has been the history of a central and united nation. To try to install a foreign model, foreign to our history, would only bring us misfortune and chaos". Other individuals, among whom it is believed both Rayón and Morelos were with them, supported the idea of a central state, although they were not against some autonomy for the Mexican provinces -essentially an administrative decentralization-, if that guaranteed the continuity of the union between Mexico and Central America. Bustamante and individuals close to him were quickly dubbed as the Centralists, as they certainly were.

Among the so-called Federalists, there were divergent positions, since while there were opinions in favor of replicating the model coming from the United States, other people advocated a Mexican-style federalism, which was not a copy of any other federal model, but rather one that was adapted to the certainly centralized conditions of the Mexican State. Thus, radical federalists were usually associated more with confederalism, while moderate federalists were more like central federalists. In the moderate camp their leadership was assumed by people like Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, who after returning from a joint trip to both the United Kingdom and the United States returned to Mexico in mid-1816 and was quickly allowed to be part of the Constituent Congress because of his experience. Teresa de Mier, along with other individuals such as Francisco Javier Mina [2], opposed the idea of granting sovereignty to the provinces, although they were not against granting them autonomy, since "we propose a reasonable and moderate federation, a federation convenient to our little enlightenment and to the circumstances of an imminent war", in other words, the problem was not federalism itself, but the conditions in which Mexico found itself after centuries of central management: a radical federalist model would be counterproductive, so a gradual transition had to be adopted where, at least for a time, the provinces would not have sovereignty until the conditions for it were met. [3]

Father Mier and Francisco Javier Mina, respectively

Among the radical federalists there was no central figure that gave them a certain favoritism, partly because all those who could have been considered radical federalists were not in Mexico at that time, with the exception of the priest Juan Cayetano Gómez de Portugal y Solís, who served as representative of Jalisco and openly advocated a confederation [4]. Other radicals also took positions similar to those of Portugal and Solís, although with different nuances regarding the degree of sovereignty that the provinces should represent, especially because the application of the Constitution of Valencia was only short-lived, so the regionalisms that occurred in the regions of New Spain had less force than in other circumstances would have been the case [5] Teresa de Mier accused the radicals of not knowing the reality of the United States, a country they extolled as a model to follow, arguing that any mention of the "sovereignty of the states" was found only in the Articles of Confederation of 1777, a document that Mier considered "almost led the Northern nation to its collapse because of the deficiency of its design, which left the federal state with its hands tied, and which possessed almost no power". [6] For the moderates, both a federal state and the non-existence of co-sovereignty were compatible, and they saw in the Constitution of Valencia the best example of administrative decentralization without losing the idea of a central state strong enough to guarantee national unity.

It must be understood that, to a certain extent, the conditions in which the nascent republic found itself in 1816 proved the moderates right: although the economy was to a large extent damaged by the war, during the government of the Supreme Junta led by Hidalgo, efforts were made to keep the exchange of goods and the economic control of Mexico City connected to other regions of New Spain, Thus, although the siege of the capital in 1813 and the subsequent general collapse of New Spain may have provoked the "rebirth" of regional trade guilds and the primordial development of local markets in different places, once the republican power was established in a large part of the country, this regional development was not truncated, but halted. This does not detract from the fact that, for example, different individuals and groups sought to diversify trade in order to eliminate the monopolization of part of Mexico City and the ports of Veracruz and Oaxaca, respectively. The disputes between moderates and radicals, understood in this way, were not only political but also economic in nature.

The centralists, at least to some extent aligned with the interests of the "central" provinces of Mexico, quickly colluded with the moderates, and in view of the favorable position of the Directory, it was a fact that Mexico would not adopt a confederal model. However, the demands of the Central American representatives, who threatened to invalidate the Treaty of Union between the two countries, forced a compromise on the part of the moderate federalists, who did not want to lose the support of either the centralists or the Central Americans, a devolution of power: the provinces of what was New Spain proper would be less autonomous than those that were integrated from Central America, which would have the right to local constitutions. However, the moderate federalists were clear: no province could be considered sovereign (at least de iure), nor would it have the right to secede from the rest of the country, but they kept the promise that, gradually, the powers that each province would have would be increased according to population growth, economic development, and in general, if "this was the will of the inhabitants of the provinces". The Central Americans, although hesitant, accepted the compromise. The centralists, although not necessarily in agreement, could not oppose it, largely because it was either that or risk the provinces becoming radicalized and adopting radical federalism. The radicals, although totally opposed to the compromise, had neither the charisma nor the political support necessary to legally reject this -emphasis on legally-, so either in some cases they de facto accepted this, or they sought to provoke uprisings in places like Yucatán or Jalisco, without much success. [7]

In addition to the debates around federalism or centralism, there were others that, to a greater or lesser extent, filled the front pages of the first newspapers of independent Mexico. Among the first, we have the question of citizenship, since, although the Constitution of 1813 recognized Liberty and Equality as values on which the nation was founded, some legislators, protected by the political development of the United States and the instability of the French and Spanish regimes, promoted the limitation of citizenship by means of censitary suffrage: although there was no clear consensus, it was expected that individuals who could vote would know how to read and write, as well as earn a high enough salary to be considered citizens. [8] The idea, although against the values of universal suffrage given by the Constitution, was not necessarily frowned upon, since, in the minds of those legislators who promoted it, they were not attacking or undermining republican institutions, but actually improving them, in that eventually any individual, as long as he made enough effort, could accede to the position of citizen. In other words, it was a reformist position, and not a radical one like universal suffrage, without abandoning the principles of a good part of the liberals of the time; or to put it another way: the problem was not the republic in the strict sense, but the degree of democratic openness: they conceived of the republic as something different from a democracy, two different models of government, a position not so far removed from their American counterparts. [9]

Although many centralists were in favor of imposing some sort of limitation on citizenship requirements, the discussions went nowhere, due in part to the fact that no one really agreed on what limitations to place on citizenship. Some individuals advocated that citizens and politicians should at least be able to read and write, but this resulted in people arguing whether Spanish should be the only language in political affairs, or whether those who knew Mexicano [10] or other native languages were also valid to vote or assume public office. Carlos María de Bustamante, in particular, advocated the use of Mexicano as the language of administration in towns where the majority of the population spoke it, or where other native languages existed, since Mexicano at that time acted as a lingua franca among a good part of those who did not speak Spanish, so that by reducing the number of languages spoken to only two, it could both include the Indians in the nascent national political life, and guarantee their education and civilization to the standards sought from the new Mexican society. Vicente Guerrero agreed, given his experience with the Indian republics in Tecpán, so he proposed making it obligatory for every individual who knew Spanish or Mexicano to be able to vote or be voted for, as well as maintaining and promoting the use of Mexicano in legal matters (sentences, courts, translations of laws and decrees), and bilingual learning where necessary, so that no one would be left behind or be ignorant of their rights and obligations as Mexicans. However, among moderate and radical federalists there was a view that the language of public administration should be Spanish only, arguing that the bureaucracy could not afford to muddle over the use of multiple languages, as well as the fact that Spanish, "unlike the languages of the Indians, was a civilizing language", which should be encouraged among the natives, either out of paternalism, contempt for their cultures, or, on the contrary (ironically), to seek their integration into Mexican society, their emancipation and enlightenment, so to speak. [11]

It must be understood that, to a certain extent, the conditions in which the nascent republic found itself in 1816 proved the moderates right: although the economy was to a large extent damaged by the war, during the government of the Supreme Junta led by Hidalgo, efforts were made to keep the exchange of goods and the economic control of Mexico City connected to other regions of New Spain, Thus, although the siege of the capital in 1813 and the subsequent general collapse of New Spain may have provoked the "rebirth" of regional trade guilds and the primordial development of local markets in different places, once the republican power was established in a large part of the country, this regional development was not truncated, but halted. This does not detract from the fact that, for example, different individuals and groups sought to diversify trade in order to eliminate the monopolization of part of Mexico City and the ports of Veracruz and Oaxaca, respectively. The disputes between moderates and radicals, understood in this way, were not only political but also economic in nature.

The centralists, at least to some extent aligned with the interests of the "central" provinces of Mexico, quickly colluded with the moderates, and in view of the favorable position of the Directory, it was a fact that Mexico would not adopt a confederal model. However, the demands of the Central American representatives, who threatened to invalidate the Treaty of Union between the two countries, forced a compromise on the part of the moderate federalists, who did not want to lose the support of either the centralists or the Central Americans, a devolution of power: the provinces of what was New Spain proper would be less autonomous than those that were integrated from Central America, which would have the right to local constitutions. However, the moderate federalists were clear: no province could be considered sovereign (at least de iure), nor would it have the right to secede from the rest of the country, but they kept the promise that, gradually, the powers that each province would have would be increased according to population growth, economic development, and in general, if "this was the will of the inhabitants of the provinces". The Central Americans, although hesitant, accepted the compromise. The centralists, although not necessarily in agreement, could not oppose it, largely because it was either that or risk the provinces becoming radicalized and adopting radical federalism. The radicals, although totally opposed to the compromise, had neither the charisma nor the political support necessary to legally reject this -emphasis on legally-, so either in some cases they de facto accepted this, or they sought to provoke uprisings in places like Yucatán or Jalisco, without much success. [7]

In addition to the debates around federalism or centralism, there were others that, to a greater or lesser extent, filled the front pages of the first newspapers of independent Mexico. Among the first, we have the question of citizenship, since, although the Constitution of 1813 recognized Liberty and Equality as values on which the nation was founded, some legislators, protected by the political development of the United States and the instability of the French and Spanish regimes, promoted the limitation of citizenship by means of censitary suffrage: although there was no clear consensus, it was expected that individuals who could vote would know how to read and write, as well as earn a high enough salary to be considered citizens. [8] The idea, although against the values of universal suffrage given by the Constitution, was not necessarily frowned upon, since, in the minds of those legislators who promoted it, they were not attacking or undermining republican institutions, but actually improving them, in that eventually any individual, as long as he made enough effort, could accede to the position of citizen. In other words, it was a reformist position, and not a radical one like universal suffrage, without abandoning the principles of a good part of the liberals of the time; or to put it another way: the problem was not the republic in the strict sense, but the degree of democratic openness: they conceived of the republic as something different from a democracy, two different models of government, a position not so far removed from their American counterparts. [9]

Although many centralists were in favor of imposing some sort of limitation on citizenship requirements, the discussions went nowhere, due in part to the fact that no one really agreed on what limitations to place on citizenship. Some individuals advocated that citizens and politicians should at least be able to read and write, but this resulted in people arguing whether Spanish should be the only language in political affairs, or whether those who knew Mexicano [10] or other native languages were also valid to vote or assume public office. Carlos María de Bustamante, in particular, advocated the use of Mexicano as the language of administration in towns where the majority of the population spoke it, or where other native languages existed, since Mexicano at that time acted as a lingua franca among a good part of those who did not speak Spanish, so that by reducing the number of languages spoken to only two, it could both include the Indians in the nascent national political life, and guarantee their education and civilization to the standards sought from the new Mexican society. Vicente Guerrero agreed, given his experience with the Indian republics in Tecpán, so he proposed making it obligatory for every individual who knew Spanish or Mexicano to be able to vote or be voted for, as well as maintaining and promoting the use of Mexicano in legal matters (sentences, courts, translations of laws and decrees), and bilingual learning where necessary, so that no one would be left behind or be ignorant of their rights and obligations as Mexicans. However, among moderate and radical federalists there was a view that the language of public administration should be Spanish only, arguing that the bureaucracy could not afford to muddle over the use of multiple languages, as well as the fact that Spanish, "unlike the languages of the Indians, was a civilizing language", which should be encouraged among the natives, either out of paternalism, contempt for their cultures, or, on the contrary (ironically), to seek their integration into Mexican society, their emancipation and enlightenment, so to speak. [11]

Indian towns (ALL the black dots in the map) in New Spain, 1800

(Author note: Idk why it excludes Northern Mexico and Central America)

Since the debates got nowhere due to the variety of opinions, it ended up leaving universal male suffrage (with nuances) in the constitutional amendments, but it was accepted that at least public servants and members of the Supreme Congress, Government and Tribunal of Justice should know how to read and write as requirements to be elected to such positions, although it was not specified in what language. In this sense, the supporters of individuals as sovereigns (popular sovereignty) triumphed at least partially over those who feared the tyranny of the majority, democratic demagogy, as some said. Likewise, the possibility of using the Mexicano language in legal cases would be maintained (at least for the time being), although another language could be used as long as there were interpreters who could speak Spanish for the registration of the cases. Each Indian republic could use the language that "suited the happiness of its inhabitants" as thanks for their efforts during the War of Independence [12]. The Constitution, at the same time, was to be published in Mexicano once it had been reformed, in an attempt to ensure that as many Indians as possible (whom it was proposed from that point on to call Indigenous peoples, to eliminate racist distinctions) would be loyal to the republican government and aware of their rights and obligations: a primitive form of civic nationalism to form Mexican nationality.

Once these points had been raised, the powers to be assumed by each federate power (the moderate federalists advocated this name, as opposed to federal), especially the Supreme Government, were redefined. While there was a fear (as previously explained, justified) of the possibility of the emergence of tyrants and despots as a result of the vision of the monarch as an absolute Executive, the experience of the war made it clear that, at least in times of war or internal crisis (such as a rebellion), it was necessary to give extraordinary powers to the members of the Supreme Government, the national collective presidency. The Directory advocated in particular (more as a request than a demand) that the number of members of the Supreme Government be reduced to three, since it was assumed that fewer members in the same period would help to make decisions more quickly. Moreover, if two members of the Government could not agree on something, the third could act to break the indecision of the first two by casting the deciding vote. Other individuals went further and called for dissolving the Supreme Government to form an individual presidency, more in keeping with the nascent republics in the Americas, but this was rejected [13]: the joint actions of the Directory demonstrated that a collective presidency was possible, even if the individual who held the rotating post of President of the Republic was the one who de facto had the greater protagonism and leadership, as happened during the war. Of the three individuals who were to make up the next Directory (now more like a Triumvirate), one would be elected by the Central American deputies, since they would thus have a voice in the decisions of the Supreme Government.

As for the powers that the Supreme Government could acquire, beyond new procedures (especially at the diplomatic level, both with other countries and with the Vatican through concordats), it was granted the power both to reject or send to modify bills of the Supreme Congress (at least once, and under justification); and to have the ability to possess emergency powers under circumstances that forced Congress to grant them, but under the guarantee that these powers were temporary, and were codified by law, to avoid arbitrariness on the part of the Executive. In this way, although the Supreme Government continued to be subordinated to Congress, its hands would no longer be totally tied to carry out emergency actions if the country so required. Future figures such as Anastasio Bustamante or Lucas Alamán would praise the measure once settled in Mexico, but would continue to promote a presidential system, since even despite the measures taken by the constitutionalists, a system of checks and balances still did not fully exist, as was the case in the United States. [14]

Less relevant issues for the Mexican constitutionalists were the role of the Tribunal of Residence (which some considered abolishing and transferring its functions to the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, and others promoted keeping it as a fourth constitutional power that would watch over compliance with the Constitution itself through the fight against corruption and heresy), or the issue of women, even though Morelos himself recognized the efforts of the opposite sex in the struggle for Independence [:...].

Once these points had been raised, the powers to be assumed by each federate power (the moderate federalists advocated this name, as opposed to federal), especially the Supreme Government, were redefined. While there was a fear (as previously explained, justified) of the possibility of the emergence of tyrants and despots as a result of the vision of the monarch as an absolute Executive, the experience of the war made it clear that, at least in times of war or internal crisis (such as a rebellion), it was necessary to give extraordinary powers to the members of the Supreme Government, the national collective presidency. The Directory advocated in particular (more as a request than a demand) that the number of members of the Supreme Government be reduced to three, since it was assumed that fewer members in the same period would help to make decisions more quickly. Moreover, if two members of the Government could not agree on something, the third could act to break the indecision of the first two by casting the deciding vote. Other individuals went further and called for dissolving the Supreme Government to form an individual presidency, more in keeping with the nascent republics in the Americas, but this was rejected [13]: the joint actions of the Directory demonstrated that a collective presidency was possible, even if the individual who held the rotating post of President of the Republic was the one who de facto had the greater protagonism and leadership, as happened during the war. Of the three individuals who were to make up the next Directory (now more like a Triumvirate), one would be elected by the Central American deputies, since they would thus have a voice in the decisions of the Supreme Government.

As for the powers that the Supreme Government could acquire, beyond new procedures (especially at the diplomatic level, both with other countries and with the Vatican through concordats), it was granted the power both to reject or send to modify bills of the Supreme Congress (at least once, and under justification); and to have the ability to possess emergency powers under circumstances that forced Congress to grant them, but under the guarantee that these powers were temporary, and were codified by law, to avoid arbitrariness on the part of the Executive. In this way, although the Supreme Government continued to be subordinated to Congress, its hands would no longer be totally tied to carry out emergency actions if the country so required. Future figures such as Anastasio Bustamante or Lucas Alamán would praise the measure once settled in Mexico, but would continue to promote a presidential system, since even despite the measures taken by the constitutionalists, a system of checks and balances still did not fully exist, as was the case in the United States. [14]

Less relevant issues for the Mexican constitutionalists were the role of the Tribunal of Residence (which some considered abolishing and transferring its functions to the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, and others promoted keeping it as a fourth constitutional power that would watch over compliance with the Constitution itself through the fight against corruption and heresy), or the issue of women, even though Morelos himself recognized the efforts of the opposite sex in the struggle for Independence [:...].

Excerpts from "History of Women in Mexico", 2023

After the end of the War of Independence, some individuals began to argue about the actions of insurgent women during the independence conflict. The great majority did not tend to recognize their value, although neither did they dare openly reject their contribution, since it was counterproductive. The Directory during the war was forced to accept any help, be it material or military, that could come from those women who were willing to die for the nascent homeland, or to take revenge for the loss of their husbands, sons or relatives in general. For example, the Plan of Reorganization of the population in mid-1813 after the insurgent victory in Mexico City, gave women both an obligation and a (de facto) right: the first was the "obligation to spin and perform other labor to alleviate the burdens of marriage"; the second was the de facto right to bear arms and even to assist the insurgent troops, or else:

The first three classes, of ecclesiastics, children, old men and women, are of course exempt from taking up arms, but they are not forbidden to bear arms of all kinds, to safeguard their persons; even to assist, joining the troops in case of a difficult action with the invading enemy [...] [15].

Or put another way: women could not be prevented from taking up arms against the Spanish government, either for themselves or to safeguard other insurgents. However, this decree only legalized what had already been a reality since the beginning of the war: the passive and active participation of women in the different moments of the conflict, as is the case of the already known Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, who was one of the participants in the Grito of Queretaro, or Leona Vicario, wife of the constitutionalist Andrés Quintana Roo, and active participant during the siege of Mexico City and the counter-realist campaigns during La Venganza; which earned them both recognition as Mothers of the Homeland, the best distinction a woman could have received at that time. However, there are still women who unfortunately never had their names revealed to history, but who contributed anonymously to take care of the homeless, protect the infants, give food, water and shelter to the insurgents, or even if it was necessary to take any object from them; or even if necessary to take any object at hand and use it as a weapon and help in battles as nurses or auxiliary soldiers, which logically led to the campaigns of royalist terror did not distinguish gender, being these anonymous heroines outraged, murdered, sexually abused, or physically wounded as punishment/torture.

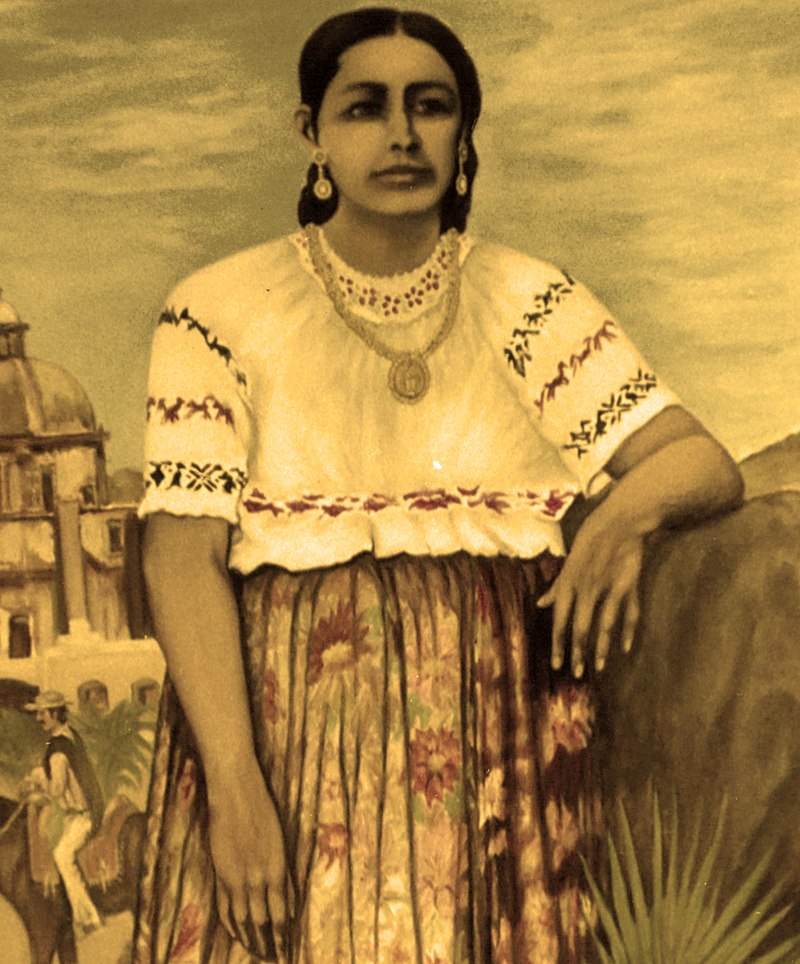

Leona Vicario (as a young girl) and Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, respectively

Other women, less conspicuous in the annals of Mexican history, but who we believe it is necessary to rescue from their forgotten condition, contributed in different ways, with the above examples being applicable to them as well: Manuela Medina, also called La Capitana, one of the few women who were officially part of the insurgent army, leading battalions in the south of the country and participating during the collapse of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. Mariana Rodriguez de Soto, a woman based in Mexico City, openly called for the hanging of the Viceroy after his capture by Hidalgo and the insurgents and was one of the auxiliaries during the siege of Mexico City, acting both as a soldier and as a nurse. Antonia Nava de Catalán was known as La Generala because she always accompanied her husband, General Nicolás Catalán in battle, acting as his right hand and advisor. And so we can go on with many more women.

The portraits of Manuela Medina and Antonia Nava de Catalán, respectively (there's no portrait of Mariana Rodriguez del Soto, unfortunately)

In any case, once the war was over, except for the first two mentioned above, the rest of the women practically disappeared again from Mexican political and military life, although some male individuals recognized them for their efforts, as was the case of José Joaquin Fernandez de Lizardi, popularly known as El Pensador Mexicano. Lizardi, author of political literary works such as El Periquillo Sarmiento, was one of the first to question whether women were really unfit to hold public office or vote, based on the experience he had during the war as well as in the early post-war years, as evidenced in his discussion with Anita la tamalera. While Lizardi was not a feminist in the least, his plea to the Mexican constitutionalists to promote female education at least at the basic level (handicrafts, literature, mathematics, literacy, etc.) and his debates "with himself" and to those who read him about women's suffrage and equality before the law between men and women (whom he considered to have no impediments beyond discipline and educational degree) to be part of the government, were relevant enough to be recorded as the first serious attempt to promote women, free them from the ignorance in which they were encumbered by obsolete institutions, and draw them into the Enlightenment that their male peers in theory already enjoyed. [16]

Although Lizardi's words did not resonate with the vast majority of constitutionalists, it was argued that, if the Constitution mentioned that the inhabitants deserved to be enlightened in the fight against ignorance, women should be educated under these same principles, since while the quality of citizen was only reserved for men, women were also inhabitants and deserved to be happy. Therefore, the concession to provide basic education and "according to their condition" to women indistinctly was approved. A first step which, although insufficient, guaranteed de iure that at least women had the right to read and write like their male counterparts. Likewise, the Mexican State agreed to offer a monthly salary to all women who had participated in the independence conflict as long as they had been part of the nascent Army, but there was no debate as to whether or not women could be part of the Army once the war was over, even though they were de facto rejected, at least initially.

Although Lizardi's words did not resonate with the vast majority of constitutionalists, it was argued that, if the Constitution mentioned that the inhabitants deserved to be enlightened in the fight against ignorance, women should be educated under these same principles, since while the quality of citizen was only reserved for men, women were also inhabitants and deserved to be happy. Therefore, the concession to provide basic education and "according to their condition" to women indistinctly was approved. A first step which, although insufficient, guaranteed de iure that at least women had the right to read and write like their male counterparts. Likewise, the Mexican State agreed to offer a monthly salary to all women who had participated in the independence conflict as long as they had been part of the nascent Army, but there was no debate as to whether or not women could be part of the Army once the war was over, even though they were de facto rejected, at least initially.

Excerpts from "Pax Mexicana: Territorial Ambitions in 19th Century Mexico", 2020.

During the War of Independence, it is well known that the insurgent government sought to unify the so-called America Septentrional, a way of speaking of Spanish North America, which included the Captaincy General of Guatemala. The nascent Mexican state, which assumed itself to be the legitimate heir of the Supreme National Junta, advocated the unification of all the lands of "Mexican America", which also included Cuba, so the Constitution of 1813 made clear Mexican expansionism towards the whole of Central America except for Panama, and the Captaincy General of Cuba, leaving unfinished business as to whether or not the Captaincies of Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico should also be taken, since there was no genuine interest from practically anyone (with the exception of Agustín de Iturbide and those close to him) in recovering those lands.

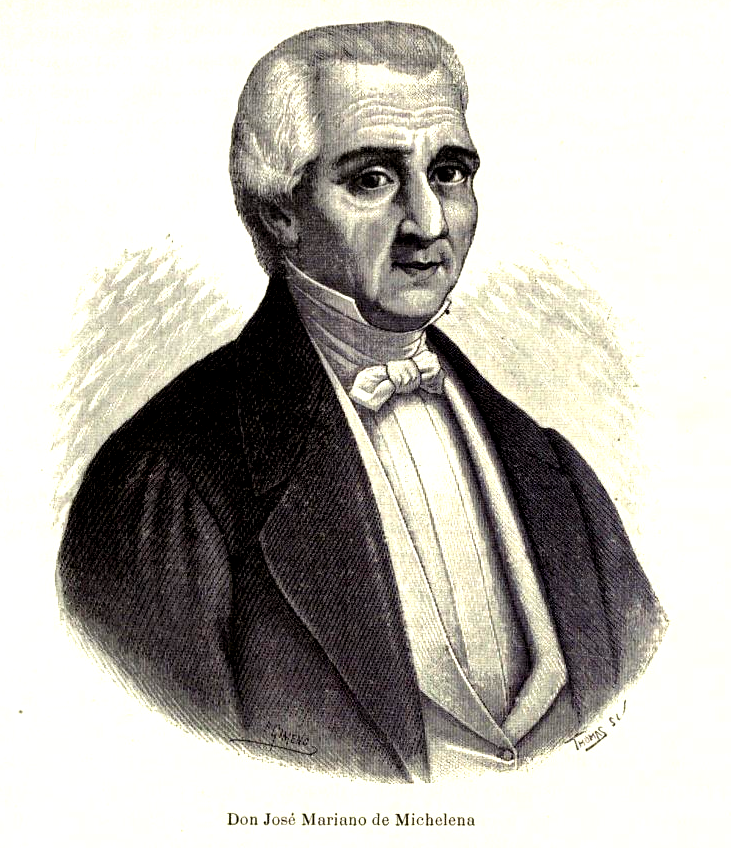

However, recent information brought to light has shown that after the Independentist victory in 1815, there was already talk about the Captaincy General of the Philippines. Although it was already known that there were individuals who were in favor of a Mexican expansion towards Asian Spain, such as Simon Tadeo Ortiz de Ayala [17], who advocated the monetary and mercantile benefits of such a union between Filipinos and Mexicans, what was not known was the influence he had, together with other individuals, such as Juan Francisco de Azcarate [18], Fray Melchor de Talamantes [19], Mariano Michelena, and later on, Lucas Alamán [20]; who had a unanimous position:

Mexico's territories included the Philippine Islands.

Of course, in 1815 such an ambition was materially impossible, given that the country was on the verge of bankruptcy, so it was largely set aside during the debates of 1816. However, the interventions of Ramón Fabié, an engineer and military man from Manila and participant in the War of Independence [21], as well as other Creoles of Filipino origin, influenced by the Mexican victory, led to an unofficial promise, a quasi-secret pact (at least in the eyes of Spain) between different Mexican politicians, which included Morelos, Iturbide and the future Guadalupe Victoria, at that time still called José Miguel Fernandez y Felix: Mexico would aid the Philippines in the event of a rebellion, sending men, arms and food.

Lucas Alamán, Juan Francisco de Azcarate, Mariano Michelena and Guadalupe Victoria, respectively; all influenced by the idea of liberating the Philippines, independently of why/the motives.

To avoid political problems, it was left to chance whether the Philippines, once free, would be united with Mexico or maintain a relationship of fraternity and brotherhood as sister republics. People like Fabié would be sent to Manila in a hidden way to influence other Creoles, at that time still dominant in the political sphere of the Captaincy General, to determine if a "peaceful" change of government was possible, although there was not much hope for it. The port of Acapulco would send contraband little by little, until there were enough men, and the opportunity was given to take power violently. For his part, Fabié personally thought of recruiting people close to his family, such as his brother-in-law, Joaquín María Bayot [22], to influence them to fight against Spain, although it would take time, since the situation of the Creoles in Spain was relatively comfortable in comparison with their American counterparts. Yet.

As for the secret pact, it also recognized the "imperious necessity" of helping the Cubans' efforts to achieve their independence, although in this case it did make clear the Mexican territorial ambitions, an idea that would become known as the Pax Mexicana. The secret pact was maintained even after suggestions by envoys from European countries that Mexico officially abandon its annexationist stance, which although diminished in their rhetoric, were not eliminated, even if it meant not being recognized by Spain. In the opinion of Mexican politicians, the Pax Mexicana was more important than the recognition of a country that had hurt them, that murdered innocents and combatants.

After the events of [...]...

The so-called Reform Act of 1816-17, sometimes called the Constitution of 1817, although the Constitution of 1813 was never formally replaced, modified most of the political aspects of it. Officially, the Provisional Constitutional Decree of the Mexican Republic became the Federated Constitution of the Mexican Republic, a subtle change but one that reflected that the Constitution was official and formalized, and not just a provisional Magna Carta in times of war.

The First Title (Fundamental Principles) delimits:

The First Title (Fundamental Principles) delimits:

- The form of government as a federated, representative and popular republic (Chapter I);

- The State religion as Roman Catholicism, although the entry of non-Catholics is regulated under certain circumstances and always respecting Catholic supremacy (Chapter II);

- Popular sovereignty, largely unchanged from the Constitution of 1813, although senators are included as representatives of the people (Chapter III);

- On citizenship, the requirements to be a citizen for both nationals and naturalized foreigners, the ways to lose citizenship and the ways to be suspended from it, with the right to recover it (Chapter IV);

- On the law and the distinction between federated laws and state laws, which are subordinate to the former, the federated government having the right to annul any state law that contradicts the federated ones (Chapter V);

- On the rights of Mexicans, whether citizens or inhabitants; Although it does not change greatly with respect to the original document, the defense of every freedman who arrives in Mexico is made manifest, as well as basic education for women (Chapter VI);

- On the obligations of Mexicans (Chapter VII);

- On the states, formerly provinces, of their degree of powers (the granting of sovereignty is not explicit), their internal organization and political administration, the states that make up the country, the claim on Cuba, and on the federated territories (Chapter VIII);

- On the rights of the states: ability to elect their own judges, monetary autonomy under federal tutelage, formation of militias, schools and their own laws or decrees as long as there is no contradiction with the federated laws, etc.; local constitutions for the Central American states (Chapter IX);

- On the obligations of the states: formation of governments in accordance with the federated Constitution, publication of all laws or state decrees without censorship, collaborating with other states in criminal cases, delivering copies of all their laws and decrees to the federated authorities, accounting for all monetary and financial expenses, or delegate part or all of its powers to the federated government in extraordinary cases without the possibility of appeal, etc. (Chapter X);

- On the restrictions of the states: declaring war individually, assuming powers not given by the federated government, etc. Chapter XI).

- The Supreme Authorities, that is, the federated government, divided into the legislative (Supreme Mexican Congress), executive (Supreme Mexican Government) and Judicial (Supreme Tribunal of Justice) powers, as well as its location in a Federated District, which would be Mexico City (Chapter I);

- On the Supreme Mexican Congress, its composition into a House of Representatives and a Senate (Chapter II);

- On the House of Representatives, the requirements and restrictions to be a deputy, its duration in two years, and its inviolability of opinion with limitations (Chapter III);

- On the election of deputies, through population representation (one deputy for every fifty thousand people or fraction of thirty thousand), the guarantee that every territory can have a deputy, and the universal masculine nature of suffrage to elect the deputies through indirect suffrage (Chapter IV);

- The degrees of indirect election, divided into three: Parish, Partido and State Electoral Boards, and the procedures in each electoral board for the election of the electors who will eventually elect the representative(s) of each state (Chapters V, VI and VII);

- On the Senate, the requirements and restrictions to be a senator, equal representation between states since every state has the right to elect two senators, on the election of senators by the legislatures of their states, etc. (Chapter VIII);

- The powers/faculties of the Supreme Congress in general, as well as the exclusive powers possessed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate (Chapter IX);

- On the procedure to form, debate and approve or reject laws, the limitation of the Senate of not being able to reject any project coming from the House of Representatives, the capacity of the Supreme Government and local congresses to propose bills or decrees, the veto of the Supreme Government under limitations, the veto of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, etc. (Chapter X);

- On the ordinary sessions of the Supreme Congress and the possibility of holding extraordinary sessions when necessary (Chapter XI);

- On the Supreme Mexican Government, its composition in a Triumvirate and the biannual rotation of the honorary position of President of the Republic, the requirements to be part of the Executive, time in office, etc. (Chapter XII);

- On the election of the members of the Supreme Government in charge exclusively by the House of Representatives, with two of the members of the Supreme Government elected by the generality of the deputies, and one more elected by the deputies of Central American origin, as well as the procedure in both cases (Chapter XIII);

- On the powers of the Supreme Mexican Government, which were increased to a relative extent due to the formalization of the Constitution, as well as the inclusion of the possibility of granting emergency powers to the Executive temporarily and under the guidelines that Congress considers (Chapter XIV);

- On the limitations and obligations of the Supreme Government, including the non-possibility of the Supreme Government to assume extraordinary powers without permission from Congress, or to maintain powers indefinitely (Chapter XV);

- On the General Treasury, which would be named as the Secretariat of the Treasury, as a delimited body to regulate everything related to fiscal matters, especially those related to expenses and income; and with the obligation to form state sections (Chapter XVI);

- On the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, its composition in nine members, of which one assumes the position of President, its time in office, its division into two chambers, its election at the hands of the Supreme Government, etc. (Chapter XVII);

- On the powers of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, which include in the Act of Reforms the ability to force the Catholic Church to be faithful to the principles of "What is from Caesar to Caesar, and what is from God to God" (the non-interference of religious authorities in matters that do not concern them in matters of State) through the use of recourse of force, as well as the authorization to form a Superior Ecclesiastical Court, which would act hand in hand with the Church to reinforce that principle, and prevent abuses towards priests and other members with respect to their prelates, etc. (Chapter XVIII);

- On the circuit and district courts, as well as the legal survival of the republics [of Indians] and their coexistence with constitutional city councils [ayuntamientos], as well as the use of native languages in the same republics on condition of the existence of a translator into Spanish, and full obedience to the republican government, etc. (Chapters XIX and XX);

- On the administration of justice, that is, the rights of those arrested and prisoners, the permanence of ecclesiastical and military jurisdictions, and the prohibition of seizing property except in cases where it is necessary (Chapter XXI);

- On the Tribunal of Residency, a fourth de facto power that resolves everything that has to do with residency lawsuits towards all the members of the federated government, with the candidates being chosen by the State Electoral Boards the day after the election of the deputies. -one for each state- and finally ratified by the House of Representatives, which must elect seven members; as well as his time in office, the existence of a president in the Tribunal, etc., (Chapter XXII);

- On the function of the Tribunal of Residence: organize trials of residence against any official of the federal government who, during his position, committed crimes of a high nature, so that once his post ends, the trial takes place and determines whether he is innocent or guilty, and the actions to be taken in case the second case applies; with citizen of the country having the right to accuse a federal official, etc. (Chapter XXIII);

- On the observance of the Constitution, prohibiting its modification until the year 1820, and that in case of modification, addition or elimination of its articles once that year arrives, ⅔ of the votes of the Supreme Congress are required for any change, as long as it does not seek to modify the country's form of government (Chapter XXIV);

- On the sanction and promulgation of the Constitution, which beyond indicating its promulgation in a formal manner, gives authorization for its printing in Nahuatl if it is considered necessary, although printing in Spanish is privileged.

[1] There is a misconception that believes that C. M. Bustamante was a conservative, which is a lie: Bustamante, despite his fervent Catholicism (and support for centralism, since he saw in a federal state the fragmentation of the unity of the territories that formed the Viceroyalty of N. S.), was in favor of individual guarantees, especially freedom of the press, and was a republican to the death; moreover, while other characters saw the "construction of the Mexican historical identity" in the viceroyalties, Bustamante went further back, towards the Mexica/Aztec Empire.

[2] The repercussions of an early Mexican Independence in Spain remain to be seen, but I am almost certain that the monarchist reaction on the part of Ferdinand VII to the prospect of the Constitution of Valencia and the Spanish and Novo-Hispanic/Mexican liberals will be much worse TTL. Thus, liberals like Mina now have a perfect excuse to flee Spain and join Mexico, given their disdain for the Spanish monarchy.

[3] OTL, Teresa de Mier in the Constituent Congress of 1823-24 voted in favor of Mexico being constituted as a "popular, representative and federal republic", but voted against the formula "free, sovereign and independent states", arguing that the federal model of the United States was not the most adequate for the existing conditions in Mexico, since there was no real federal antecedent in Mexico.

[4] Lorenzo de Zavala, not having been incarcerated OTL, at least for the time being does not know English. Also, since he has not met Ambassador Joel R. Poinsett, he has not yet been influenced to any great extent by U.S. federalism. On the other hand, Miguel Ramos Arizpe, OTL considered the "father of federalism" in Mexico, is currently imprisoned in Spain. Evidently there are more people who were sympathetic to the radical position, but they did not have the importance or "political capital" that Arizpe or Zavala did.

[5] The opposite is true OTL: The constant application of the Cadiz Constitution between 1812 and 1814, and later, 1820-1821 (ignoring the fact that the Constitution was de facto the one used by Mexico between 1821 and 1824) allowed the development of regional interests that although they already existed, were able to begin to express themselves more freely with respect to the interests of the metropolis (in part thanks to the figure of the constitutional town councils), which helped in good measure so that, by the time of the Constituent Assembly of 1823-24, many of the provinces of Mexico were in favor of a federal project, although under different shades of meaning. Here, its shorter application and replacement by the Constitution of 1813, of a more centralist character, although it does not annul such regionalism, it weakens it.

[6] During the Constituent Assembly of 1823-24, Teresa de Mier rejected mentions of the sovereignty of the states alleging that the Constitution of 1787 had no mention of this, which is true, since, although there are reservations of powers to the states, at no time does the word "sovereignty" appear. On the contrary, the Articles of Confederation do make explicit the sovereignty of the states, as well as liberty and independence.

[7] As far as I understand, both places were bastions of federalism in Mexico: Yucatan because of its status as a Captaincy General within the Viceroyalty, which allowed it to develop with autonomy, and Jalisco because of the political-economic effects of the War of Independence, and the opening of political life after the Constitution of Cadiz OTL.

[8] OTL, during the 1830s, there were several attempts to modify the Constitution of 1824 to introduce census suffrage under requirements of knowing how to read and write, as well as earning a certain salary or owning property/capital, since this was expected to strengthen the republican system, with intellectuals and "well-to-do people" having the ability to vote. Contrary to what one might think, the proposals came from both liberals and conservatives, with even people like José María Luis Mora being in favor of the measure. Those who advocated universal (male) suffrage were considered radicals, based on previous experiences in revolutionary France (and the subsequent discrediting due to the instability of that regime).

[9] I understand that there have been debates as to whether the United States is a democracy or not, in that the U.S. government considers itself a constitutional republic, and while there have been varying degrees of democratic openness (such as universal suffrage, first for whites, then for men in general, and finally including women), that does not make the United States "inherently a democracy", a "government of the majorities". The mentality of the Mexican legislators who advocated census suffrage was close to that position, since they agreed with the principle of national sovereignty (the nation is sovereign, but not the individuals that comprise it), as opposed to the idea of popular sovereignty (the government must be representative, and therefore, must represent all individuals, which is why universal suffrage is necessary).

[10] Nahuatl, that's how it was known/called during the Colonial period and the 19th Century in general. Even today it's named like that by some Nahua communities. Other names include Nawatlahtolli or Mexikatlahtolli, for example.

[11] OTL, a consensus was never reached on whether to impose Spanish as the official language of the State de iure, but de facto this was the case. Most liberals, whether federalists or centralists, rooted in the experience of their counterparts in France or the United States, sought to improve administrative efficiency and effectiveness through the imposition of a single language, which should also help in the formation of a sense of national unity, and enforce the notion that all are equal before the law, so there should be no special treatment for the "so-called Indians", or indigenous peoples (i.e. cultural assimilation and a legally liberal, but certainly erroneous, vision). Only some liberals, such as Bustamante, Guerrero or Juan Rodriguez Puebla (who TTL at this date is still very young, unfortunately) proposed the preservation, study or use of indigenous languages, since, the fact that the law granted equality did not mean that this already existed de facto, or in other words: legal equality did not imply real equality, and the indigenous continued (and continue) in a state of discrimination and backwardness. TTL, although the mentality is more or less the same, a greater centralist influence (in general) and in particular, that of people like Bustamante and Guerrero, should help, even if only a little, to fight early on for indigenous languages.

[12] The figure of the Indian republics is not dissolved TTL, at least not in principle: OTL Morelos and the Mexican insurgents had a good base of material and human support in the Indian republics, and although the insurgents were aware that these were part of the viceregal model to separate Spaniards and Indians in different locations (and therefore, it was a discriminatory measure), they assumed that it was possible to use them in a revolutionary way: preserve them to have the support of the caciques or local indigenous chiefs/families, but integrate them into the new republican apparatus and effectively turn them into citizens adept to the Republic, without eliminating their local customs and organization, or what is the same: use a conservative model of organization for a revolutionary purpose. The Constitution of Apatzingán, in fact, respected the juridical figure of the republics, as long as they did not "establish a new system" and under reservations, that is, if that was the will of their inhabitants. This is contrary to what the Spanish politicians in the Cortes de Cadiz sought, as they eliminated the Indian republics as part of the efforts to impose equality before the law.

[13] OTL the opposite happens: the insurgent defeat in 1815 and the end of all revolutionary "effervescence" by 1823 (when the Republic is instituted) ended up being factors for the formation of a unitary Executive, as in most of the world today. TTL, the Supreme Government managed to stay afloat, and the insurgent victory allows this effervescence in favor of a collective Executive to survive for a while longer, even if it is modified to be rather functional.

[14] Alamán was inspired by both the U.S. system of checks and balances and Roman dictatorships to consider that in times of emergency it was necessary for the Mexican president to act without restraint to safeguard the nation, but that these powers should not contravene the republican system. TTL, this part is rather "unrealistic" on my part, at least partially, since Alamán is in Spain by 1816, for example; but OTL Morelos had more or less similar views regarding strengthening the Executive since, in practice, the Constitution of Apatzingán was not realistically, feasible, given the legislative supremacy over the Supreme Mexican Government; Thus, here the failures of the 1813 Constitution become evident, and the members of the Supreme Government with the prestige obtained take advantage of their opportunity to diminish a little this legislative supremacy.

[15] The decree is real and was decreed by Morelos OTL on July 7, 1813. The decree is still the same TTL (aside from the mentions related to Calleja, since he's already dead TTL), and can be seen here (in Spanish).

[16] Lizardi believed that women should be enlightened (educated) so that they would be better mothers, that they would give way to a generation of enlightened and educated men and women, a utopian society in his eyes. In his view, both men and women possessed the original sin, but both were capable of redemption. Although he discouraged women from becoming involved in political and military life (by maintaining male supremacy in these areas and considering women more suited to be mothers and wives), he recognized those who broke such molds, such as the women mentioned in this text, calling them patriots and "deserving" of the high offices of the republic, and being aware that, strictly speaking, there were no impediments beyond education, and their "talent" as mothers (from her perspective) to be part of national political life, as he tells in his response towards Anita la tamalera.

[17] OTL Ortiz de Ayala openly proposed during the First Empire the annexation of the Philippines to Mexico, as the region was considered to be dependent on Mexico. In addition, Ortiz added that the annexation of the Philippines could bring benefits in terms of development (money, goods from China, possibility of opening commercial ports in California, etc.).

[18] OTL member of the Commission on Foreign Relations during the First Empire that advocated for expansion to the Philippines. He advocated convincing the Filipinos that a union with Mexico would be beneficial to them, both politically (adoption of a liberal and just model) and economically. He shared Ortiz de Ayala's reasoning about owning the Philippine Islands to ensure Mexican control over the Pacific Ocean.

[19] Precursor of the Mexican Independence, he died of yellow fever in 1809. He proposed in 1808 a "Plan of Independence" in case Spain came under total French control, in which he mentioned the need (for both economic and military reasons) to control Cuba and the Philippines, both to defend against France and to dissuade the United States from invading New Spain.

[20] When Michelena and Alamán spoke of Spanish territories in the Cortes in Spain, they never mentioned the Philippines in the strict sense, but spoke of New Spain including Cuba and Guatemala. In addition, Alamán alluded to a "Mexican Empire" that would possess extensive land suitable for "sea to sea" trade. It follows that, at least in principle, both saw the Philippines as an integral part of New Spain, even if they did not mention it as such.

[21] Fabié died OTL in 1810 at the hands of troops commanded by Calleja.

[22] OTL was the leader of a Creole revolt in 1822 along with his two brothers, Manuel and Jose, due to the change of administration in the Philippines from being dominated by Creoles to being dominated by peninsulares.

[2] The repercussions of an early Mexican Independence in Spain remain to be seen, but I am almost certain that the monarchist reaction on the part of Ferdinand VII to the prospect of the Constitution of Valencia and the Spanish and Novo-Hispanic/Mexican liberals will be much worse TTL. Thus, liberals like Mina now have a perfect excuse to flee Spain and join Mexico, given their disdain for the Spanish monarchy.

[3] OTL, Teresa de Mier in the Constituent Congress of 1823-24 voted in favor of Mexico being constituted as a "popular, representative and federal republic", but voted against the formula "free, sovereign and independent states", arguing that the federal model of the United States was not the most adequate for the existing conditions in Mexico, since there was no real federal antecedent in Mexico.

[4] Lorenzo de Zavala, not having been incarcerated OTL, at least for the time being does not know English. Also, since he has not met Ambassador Joel R. Poinsett, he has not yet been influenced to any great extent by U.S. federalism. On the other hand, Miguel Ramos Arizpe, OTL considered the "father of federalism" in Mexico, is currently imprisoned in Spain. Evidently there are more people who were sympathetic to the radical position, but they did not have the importance or "political capital" that Arizpe or Zavala did.

[5] The opposite is true OTL: The constant application of the Cadiz Constitution between 1812 and 1814, and later, 1820-1821 (ignoring the fact that the Constitution was de facto the one used by Mexico between 1821 and 1824) allowed the development of regional interests that although they already existed, were able to begin to express themselves more freely with respect to the interests of the metropolis (in part thanks to the figure of the constitutional town councils), which helped in good measure so that, by the time of the Constituent Assembly of 1823-24, many of the provinces of Mexico were in favor of a federal project, although under different shades of meaning. Here, its shorter application and replacement by the Constitution of 1813, of a more centralist character, although it does not annul such regionalism, it weakens it.

[6] During the Constituent Assembly of 1823-24, Teresa de Mier rejected mentions of the sovereignty of the states alleging that the Constitution of 1787 had no mention of this, which is true, since, although there are reservations of powers to the states, at no time does the word "sovereignty" appear. On the contrary, the Articles of Confederation do make explicit the sovereignty of the states, as well as liberty and independence.

[7] As far as I understand, both places were bastions of federalism in Mexico: Yucatan because of its status as a Captaincy General within the Viceroyalty, which allowed it to develop with autonomy, and Jalisco because of the political-economic effects of the War of Independence, and the opening of political life after the Constitution of Cadiz OTL.

[8] OTL, during the 1830s, there were several attempts to modify the Constitution of 1824 to introduce census suffrage under requirements of knowing how to read and write, as well as earning a certain salary or owning property/capital, since this was expected to strengthen the republican system, with intellectuals and "well-to-do people" having the ability to vote. Contrary to what one might think, the proposals came from both liberals and conservatives, with even people like José María Luis Mora being in favor of the measure. Those who advocated universal (male) suffrage were considered radicals, based on previous experiences in revolutionary France (and the subsequent discrediting due to the instability of that regime).

[9] I understand that there have been debates as to whether the United States is a democracy or not, in that the U.S. government considers itself a constitutional republic, and while there have been varying degrees of democratic openness (such as universal suffrage, first for whites, then for men in general, and finally including women), that does not make the United States "inherently a democracy", a "government of the majorities". The mentality of the Mexican legislators who advocated census suffrage was close to that position, since they agreed with the principle of national sovereignty (the nation is sovereign, but not the individuals that comprise it), as opposed to the idea of popular sovereignty (the government must be representative, and therefore, must represent all individuals, which is why universal suffrage is necessary).

[10] Nahuatl, that's how it was known/called during the Colonial period and the 19th Century in general. Even today it's named like that by some Nahua communities. Other names include Nawatlahtolli or Mexikatlahtolli, for example.

[11] OTL, a consensus was never reached on whether to impose Spanish as the official language of the State de iure, but de facto this was the case. Most liberals, whether federalists or centralists, rooted in the experience of their counterparts in France or the United States, sought to improve administrative efficiency and effectiveness through the imposition of a single language, which should also help in the formation of a sense of national unity, and enforce the notion that all are equal before the law, so there should be no special treatment for the "so-called Indians", or indigenous peoples (i.e. cultural assimilation and a legally liberal, but certainly erroneous, vision). Only some liberals, such as Bustamante, Guerrero or Juan Rodriguez Puebla (who TTL at this date is still very young, unfortunately) proposed the preservation, study or use of indigenous languages, since, the fact that the law granted equality did not mean that this already existed de facto, or in other words: legal equality did not imply real equality, and the indigenous continued (and continue) in a state of discrimination and backwardness. TTL, although the mentality is more or less the same, a greater centralist influence (in general) and in particular, that of people like Bustamante and Guerrero, should help, even if only a little, to fight early on for indigenous languages.

[12] The figure of the Indian republics is not dissolved TTL, at least not in principle: OTL Morelos and the Mexican insurgents had a good base of material and human support in the Indian republics, and although the insurgents were aware that these were part of the viceregal model to separate Spaniards and Indians in different locations (and therefore, it was a discriminatory measure), they assumed that it was possible to use them in a revolutionary way: preserve them to have the support of the caciques or local indigenous chiefs/families, but integrate them into the new republican apparatus and effectively turn them into citizens adept to the Republic, without eliminating their local customs and organization, or what is the same: use a conservative model of organization for a revolutionary purpose. The Constitution of Apatzingán, in fact, respected the juridical figure of the republics, as long as they did not "establish a new system" and under reservations, that is, if that was the will of their inhabitants. This is contrary to what the Spanish politicians in the Cortes de Cadiz sought, as they eliminated the Indian republics as part of the efforts to impose equality before the law.

[13] OTL the opposite happens: the insurgent defeat in 1815 and the end of all revolutionary "effervescence" by 1823 (when the Republic is instituted) ended up being factors for the formation of a unitary Executive, as in most of the world today. TTL, the Supreme Government managed to stay afloat, and the insurgent victory allows this effervescence in favor of a collective Executive to survive for a while longer, even if it is modified to be rather functional.

[14] Alamán was inspired by both the U.S. system of checks and balances and Roman dictatorships to consider that in times of emergency it was necessary for the Mexican president to act without restraint to safeguard the nation, but that these powers should not contravene the republican system. TTL, this part is rather "unrealistic" on my part, at least partially, since Alamán is in Spain by 1816, for example; but OTL Morelos had more or less similar views regarding strengthening the Executive since, in practice, the Constitution of Apatzingán was not realistically, feasible, given the legislative supremacy over the Supreme Mexican Government; Thus, here the failures of the 1813 Constitution become evident, and the members of the Supreme Government with the prestige obtained take advantage of their opportunity to diminish a little this legislative supremacy.

[15] The decree is real and was decreed by Morelos OTL on July 7, 1813. The decree is still the same TTL (aside from the mentions related to Calleja, since he's already dead TTL), and can be seen here (in Spanish).

[16] Lizardi believed that women should be enlightened (educated) so that they would be better mothers, that they would give way to a generation of enlightened and educated men and women, a utopian society in his eyes. In his view, both men and women possessed the original sin, but both were capable of redemption. Although he discouraged women from becoming involved in political and military life (by maintaining male supremacy in these areas and considering women more suited to be mothers and wives), he recognized those who broke such molds, such as the women mentioned in this text, calling them patriots and "deserving" of the high offices of the republic, and being aware that, strictly speaking, there were no impediments beyond education, and their "talent" as mothers (from her perspective) to be part of national political life, as he tells in his response towards Anita la tamalera.

[17] OTL Ortiz de Ayala openly proposed during the First Empire the annexation of the Philippines to Mexico, as the region was considered to be dependent on Mexico. In addition, Ortiz added that the annexation of the Philippines could bring benefits in terms of development (money, goods from China, possibility of opening commercial ports in California, etc.).

[18] OTL member of the Commission on Foreign Relations during the First Empire that advocated for expansion to the Philippines. He advocated convincing the Filipinos that a union with Mexico would be beneficial to them, both politically (adoption of a liberal and just model) and economically. He shared Ortiz de Ayala's reasoning about owning the Philippine Islands to ensure Mexican control over the Pacific Ocean.

[19] Precursor of the Mexican Independence, he died of yellow fever in 1809. He proposed in 1808 a "Plan of Independence" in case Spain came under total French control, in which he mentioned the need (for both economic and military reasons) to control Cuba and the Philippines, both to defend against France and to dissuade the United States from invading New Spain.

[20] When Michelena and Alamán spoke of Spanish territories in the Cortes in Spain, they never mentioned the Philippines in the strict sense, but spoke of New Spain including Cuba and Guatemala. In addition, Alamán alluded to a "Mexican Empire" that would possess extensive land suitable for "sea to sea" trade. It follows that, at least in principle, both saw the Philippines as an integral part of New Spain, even if they did not mention it as such.

[21] Fabié died OTL in 1810 at the hands of troops commanded by Calleja.

[22] OTL was the leader of a Creole revolt in 1822 along with his two brothers, Manuel and Jose, due to the change of administration in the Philippines from being dominated by Creoles to being dominated by peninsulares.

THE FULL TEXT OF THE CONSTITUTION OF 1813, AMMENDED (ALSO KNOWN AS THE CONSTITUTION OF 1817), IN ENGLISH: HERE

As the document says, the original parts of the Constitution are in black, meanwhile the added/modified text is in red.

As the document says, the original parts of the Constitution are in black, meanwhile the added/modified text is in red.

The National Symbols, Post-Independence

After the War of Independence ended, there were some proposals to modify the already existent Mexican national symbols: that is, the flag and the Coat of Arms. One of the most known proposals was made by Father Mier, which was essentially a simplified version of the current flag:

While the flag was not necessarily rejected de iure, de facto was dismissed for its extreme simplicity. Iturbide proposed a radical change: the replacement of blue by green. He argued that, while it was true that blue represented (alongside white) the Catholic Religion and the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Mexican flag in its current state was "no different than the French or the American flags". While it was known Iturbide was aligned to a monarchist ideal of nation, and his perception was that the combination Red-White-Blue was a symbol of Republicanism, it was also true that the Mexican flag was too similar to the other countries mentioned, so it was necessary a change to reflect that Mexico was both Republican and, well, Mexican, free.

A "Commission" led by several Mexican politicians, including Carlos María de Bustamante, Father Mier and Iturbide reunited in Mexico City and started to debate alongside with the First Triumvirate (Morelos, Nicolas Bravo and Manuel José Arce) on how to update the National Symbols to reflect the fact Mexico was finally an independent, sovereign nation. Bustamante defended the inclusion of the "Aztec Past", meanwhile Iturbide argued for the elimination of anti-Spanish war trophies, and the adoption of green. Father Mier was supportive of "letting the flag remain as it is" in case nobody was able to reach an agreement. Morelos finally argued for the addition of a symbol that represented the struggle and dedication of Father Hidalgo, meanwhile José Arce disagreed with the idea of replacing the blue, since Central America was de facto represented with such color.

In the end, since nobody could affirm, it was preferible for them to try and adopt all suggestions simultaneously, aside from Father Mier's simplicity, of course. The result was the 1818 Decree on the National Symbols of the Mexican Republic: