Chapter IV, Things go Wrong

Franklin Pierce would be sworn in for his second term as president in March 1857. Democrats had also made slight gains in both houses of Congress. His second inaugural address was about the need for unity as well as Manifest Destiny. He declared that New Orleans and San Fransisco would be connected by rail would be completed by the end of his term. He talked a little bit about Nicaragua, about how that nation would be a natural friend and ally in the region. Once again, slavery was not mentioned. The House of Representatives would have 129 Democrats, 97 Whigs, and 8 Free-Soil men. There would be 34 Democrats, 26 Whigs, and 2 Free Soil Senators. Things were looking bright for the president in 1857, but his second term would soon become embroiled in controversy. In this year, everything seemed to go wrong. America would be confronted with economic and social problems, and to the majority of Americans it seemed as if Pierce was incapable of solving them.

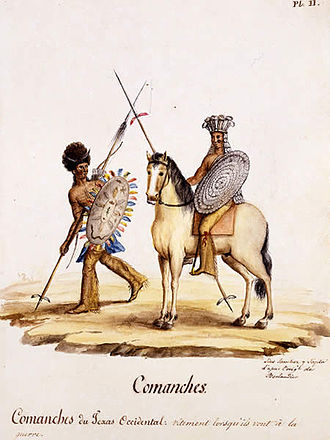

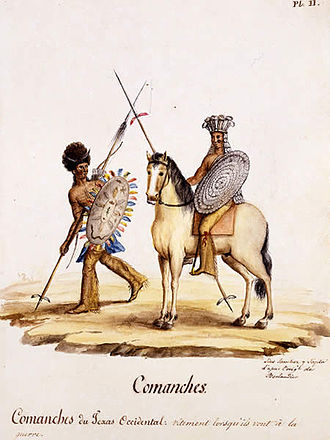

The first issue would be the railroad. The working conditions were very poor. And as the rails went further and further into Texas, the workers soon found themselves in Comanche territory. There had been intermittent conflict between settlers and Comanche for decades. In recent years, the Comanche population had been dwindling due to disease. In May, two drunken migrant laborers attempted to rape a Comanche woman, and were killed by Comanche warriors. This led to escalating tensions, and the army was deployed to the railway. Normally, this would have led to a war between the US government and the Comanche. However, the tribe had a friend in the new Vice President Sam Houston. Houston had been friendly to the Comanche during his time as President of Texas, and the Comanche remembered that. He personally traveled to Texas and helped defuse tensions. This possibly saved hundreds of lives.

(Comanche warriors)

Secretary of State William L. Marcy died in July. While Pierce was weighing the pros and cons of possible candidates, his Secretary of War began to press him. Jefferson Davis wanted the position, and Pierce was sympathetic. The president felt that he should give Davis something, considering that party delegates had passed over him for Sam Houston when they were selecting a candidate for vice president. His nomination was not without controversy. Several Senators voted against his nomination, claiming that he was a pro-slavery imperialist. Davis’ replacement would be Joseph Lane, a general in the Mexican War and a territorial delegate from Oregon. Pierce then decided to do something unprecedented: he left the country. He would travel to Nicaragua [1]. While it would have been more logical to send Davis, the new Secretary of State’s pro-annexation views meant that Pierce was not eager to send him. Pierce was motivated by diplomatic reasons but also because he wanted to see the country. He left in August and returned the next year. Sam Houston was left as acting president while Pierce was gone.

(Joseph Lane)

The president was heavily criticized for his trip to Nicaragua. And things would start to get worse for both himself and the country. Shortly after Pierce left, America entered into a recession. Opponents of the administration immediately exploited the situation. The Indianapolis Journal and the Knoxville Whig unceasingly attacked Pierce as neglecting his duties as president. The Boston Atlas blamed the recession on free trade and called for an increase in tariffs. Back at the Executive Mansion, Houston clashed with Davis. Davis had tried to galvanize members in the government to support the acquisition of Cuba, even if it meant war. Houston argued that major foreign policy decisions would need to wait until the president returned. Davis said that Pierce would support his efforts at expansion. But Davis’ plans included funding filibuster expeditions like the one in Nicaragua. A previous attempt had taken place in Cuba, and infamously failed. Houston would not budge.

When Pierce returned to Washington in early 1858, he announced that he would oppose any raises to tariffs. He invoked George Washington in defense of his free trade position. This was disappointing to many Northern Democrats, who were willing to work with Whigs on this issue. He also called for budget cuts in order to pay for the railroad (which people were beginning to realize would be more expensive then previously thought). Various small internal improvement projects were temporarily halted or turned over to the individual states. Funding for the apprehension of fugitive slaves was significantly cut, and Pierce supported this. This is seen as the first anti-slavery action of the Pierce administration. Pierce reportedly told Jane around this time that “Slavery will certainly die before Benjamin [their son] is an old man.” This is of questionable authenticity, as the first reference to this quote came from Benjamin Pierce in 1884, after both of his parents were dead.

One thing that was accomplished in 1858 was the admittance of two new states into the union. Though both the Whig and Democrat platforms had called for Minnesota and New Mexico to be admitted as states, Congress had delayed their admittance. Some pro-slavery politicians had attempted to split the New Mexico Territory into two states, in order to increase representation for slave states in the Senate. These people had held up Minnesotan statehood in the Senate. Finally, they realized their idea would not be implemented, and they gave it up. Minnesota was admitted as the 32nd state, a free state, in March 1858. New Mexico was admitted as the 33rd state, a slave state, in April 1858. New Mexico’s admission as a slave state did not bother many Northerners as it was below the Missouri Compromise line and many believed that slavery wouldn’t last long there.

(Minnesota pioneers)

New Mexico would soon see bloodshed. By the time of statehood, the railroad had just barely made it into the state. Poor working conditions mixed with the oppressive summer heat led to strikes. Pierce told Captain John Wynn Davidson, who commanded the troops at the nearest fort, that he had permission to use force to break up the strike. Fortunately, it never came to that. Between Mesilla and Tucson, the railroad workers were attacked by Apache Indians. The Apache were determined to stop the railroad from being built, and several bands of Apaches united under Cochise to resist federal encroachment. But Manuelito, a Navajo leader, was soon convinced to fight Cochise’s forces. The Navajo were facing drought and the US promised to give his people access to better land. This conflict began to spread throughout New Mexico and into Western Texas and the Utah Territory. On one side there was the United States, the Navajo, some Comanches, and some Pueblo people. On the other side there was the Apache, the Ute, and some Pueblo people. The war would last until 1860 and would result in over one thousand deaths.

(Left: Cochise, Right: Manuelito)

Pierce called for more soldiers to be deployed to New Mexico. The railway workers would continue to build the railroad, guarded by soldiers the entire way. Pierce wrote to the railroad company owners, urging them to increase the pay for their workers, and the railroad workers would eventually receive a pay raise. Theodore Frelinghuysen, Henry Clay’s 1844 running mate and opponent of Indian removal, remarked that “Pierce’s railroad is drenched in blood.” When November came, voters came to the polls with a negative view of the current administration. This was mostly due to the economy, as Whigs successfully convinced the public that protectionism could fix the economy. The incoming 35th congress would have a Whig House majority and a Whig Senate plurality. There would be 127 Whig, 101 Democrat, and 5 Free Soil Representatives. There would be 33 Whig, 31 Democrat, and 2 Free Soil Senators.

1: His visit to Nicaragua will be covered in the next chapter.

The first issue would be the railroad. The working conditions were very poor. And as the rails went further and further into Texas, the workers soon found themselves in Comanche territory. There had been intermittent conflict between settlers and Comanche for decades. In recent years, the Comanche population had been dwindling due to disease. In May, two drunken migrant laborers attempted to rape a Comanche woman, and were killed by Comanche warriors. This led to escalating tensions, and the army was deployed to the railway. Normally, this would have led to a war between the US government and the Comanche. However, the tribe had a friend in the new Vice President Sam Houston. Houston had been friendly to the Comanche during his time as President of Texas, and the Comanche remembered that. He personally traveled to Texas and helped defuse tensions. This possibly saved hundreds of lives.

(Comanche warriors)

Secretary of State William L. Marcy died in July. While Pierce was weighing the pros and cons of possible candidates, his Secretary of War began to press him. Jefferson Davis wanted the position, and Pierce was sympathetic. The president felt that he should give Davis something, considering that party delegates had passed over him for Sam Houston when they were selecting a candidate for vice president. His nomination was not without controversy. Several Senators voted against his nomination, claiming that he was a pro-slavery imperialist. Davis’ replacement would be Joseph Lane, a general in the Mexican War and a territorial delegate from Oregon. Pierce then decided to do something unprecedented: he left the country. He would travel to Nicaragua [1]. While it would have been more logical to send Davis, the new Secretary of State’s pro-annexation views meant that Pierce was not eager to send him. Pierce was motivated by diplomatic reasons but also because he wanted to see the country. He left in August and returned the next year. Sam Houston was left as acting president while Pierce was gone.

(Joseph Lane)

The president was heavily criticized for his trip to Nicaragua. And things would start to get worse for both himself and the country. Shortly after Pierce left, America entered into a recession. Opponents of the administration immediately exploited the situation. The Indianapolis Journal and the Knoxville Whig unceasingly attacked Pierce as neglecting his duties as president. The Boston Atlas blamed the recession on free trade and called for an increase in tariffs. Back at the Executive Mansion, Houston clashed with Davis. Davis had tried to galvanize members in the government to support the acquisition of Cuba, even if it meant war. Houston argued that major foreign policy decisions would need to wait until the president returned. Davis said that Pierce would support his efforts at expansion. But Davis’ plans included funding filibuster expeditions like the one in Nicaragua. A previous attempt had taken place in Cuba, and infamously failed. Houston would not budge.

When Pierce returned to Washington in early 1858, he announced that he would oppose any raises to tariffs. He invoked George Washington in defense of his free trade position. This was disappointing to many Northern Democrats, who were willing to work with Whigs on this issue. He also called for budget cuts in order to pay for the railroad (which people were beginning to realize would be more expensive then previously thought). Various small internal improvement projects were temporarily halted or turned over to the individual states. Funding for the apprehension of fugitive slaves was significantly cut, and Pierce supported this. This is seen as the first anti-slavery action of the Pierce administration. Pierce reportedly told Jane around this time that “Slavery will certainly die before Benjamin [their son] is an old man.” This is of questionable authenticity, as the first reference to this quote came from Benjamin Pierce in 1884, after both of his parents were dead.

One thing that was accomplished in 1858 was the admittance of two new states into the union. Though both the Whig and Democrat platforms had called for Minnesota and New Mexico to be admitted as states, Congress had delayed their admittance. Some pro-slavery politicians had attempted to split the New Mexico Territory into two states, in order to increase representation for slave states in the Senate. These people had held up Minnesotan statehood in the Senate. Finally, they realized their idea would not be implemented, and they gave it up. Minnesota was admitted as the 32nd state, a free state, in March 1858. New Mexico was admitted as the 33rd state, a slave state, in April 1858. New Mexico’s admission as a slave state did not bother many Northerners as it was below the Missouri Compromise line and many believed that slavery wouldn’t last long there.

(Minnesota pioneers)

New Mexico would soon see bloodshed. By the time of statehood, the railroad had just barely made it into the state. Poor working conditions mixed with the oppressive summer heat led to strikes. Pierce told Captain John Wynn Davidson, who commanded the troops at the nearest fort, that he had permission to use force to break up the strike. Fortunately, it never came to that. Between Mesilla and Tucson, the railroad workers were attacked by Apache Indians. The Apache were determined to stop the railroad from being built, and several bands of Apaches united under Cochise to resist federal encroachment. But Manuelito, a Navajo leader, was soon convinced to fight Cochise’s forces. The Navajo were facing drought and the US promised to give his people access to better land. This conflict began to spread throughout New Mexico and into Western Texas and the Utah Territory. On one side there was the United States, the Navajo, some Comanches, and some Pueblo people. On the other side there was the Apache, the Ute, and some Pueblo people. The war would last until 1860 and would result in over one thousand deaths.

(Left: Cochise, Right: Manuelito)

Pierce called for more soldiers to be deployed to New Mexico. The railway workers would continue to build the railroad, guarded by soldiers the entire way. Pierce wrote to the railroad company owners, urging them to increase the pay for their workers, and the railroad workers would eventually receive a pay raise. Theodore Frelinghuysen, Henry Clay’s 1844 running mate and opponent of Indian removal, remarked that “Pierce’s railroad is drenched in blood.” When November came, voters came to the polls with a negative view of the current administration. This was mostly due to the economy, as Whigs successfully convinced the public that protectionism could fix the economy. The incoming 35th congress would have a Whig House majority and a Whig Senate plurality. There would be 127 Whig, 101 Democrat, and 5 Free Soil Representatives. There would be 33 Whig, 31 Democrat, and 2 Free Soil Senators.

1: His visit to Nicaragua will be covered in the next chapter.

Last edited: