Chapter 12: The Southern Rebellion

President Abraham Lincoln found himself at the crossroads of destiny. The fate of the United States was now in his hands. In his eyes, the very fate of democracy and the free world depended on whether he could rise up to the situation. The fall of the US would embolden the enemies of freedom. Already there were Britons gloating about the failure of democracy, and New Yorkers whispering about joining the rebels. He had to make a decision, and save the Nation.

Lincoln’s first task was organizing his cabinet, the team which would help him fulfill his duties as president and manage the executive. To build a competent cabinet Lincoln would have to satisfy several powerful interests, ranging from Republican leaders in the east to up-and-coming western politicians, and even moderates from the nascent Southern Republican Party. Lincoln appointed Seward as Secretary of State, a magnanimous gesture for Seward had been his main rival in the National Convention. As a gesture towards Kentucky and the Border South, Lincoln appointed James Speed, the brother of his intimate friend Joshua, as Attorney General. Chase got the Treasury, leaving the War Department as the only one left of the top four departments. After much deliberation and inter-party tensions, Lincoln settled of Simon Cameron, as a way of paying back a debt towards Pennsylvania Republicans.

Caleb Smith received the Interior Department as a payment of another debt, this time towards Indiana, while Gideon Welles was appointed as Navy Secretary and Montgomery Blair as Postmaster General, but only after Blair had showed his credentials as an “Iron-Back” a Republican who refused to surrender to the South. Another Iron-Back was Chase, who strongly contrasted with Seward who went from being the champion of the “irrepressible conflict” to the hero of reconciliation.

This change astounded many Republicans, who had before seen Seward as the radical and Lincoln as the moderate. Old Whigs had rejoiced when Lincoln won the nominations instead of Seward, reportedly saying that Lincoln was a “sound moderate man” who shared nothing with the “irrepressible, higher-law, abolitionist men”. Lincoln’s moderation was such that radicals like Wendell Philipps called him “the slave-hound of Illinois”, remembering when Lincoln introduced a measure for gradual abolition in the District of Columbia that also required strict enforcement of the Constitution’s Fugitive Slave Act.

Now Lincoln was the one calling people to stand firm in the face of Southern aggression, while Seward was trying every trick to, first, prevent secession, and later keep the Border South in the Union. Some dismayed Republicans declared that Seward had now “bowed down to the slave power”. “How the mighty have fallen!”, exclaimed Chase upon hearing about this. Not helping matters was that Seward still had strong ambitions and a hearty desire for power. If he couldn’t be President, he would be the Premier of the administration and assume control of the Party as its self-appointed leader.

“Lincoln lacks will and purpose, and I greatly fear he has no power to command”, wrote Edward Bates to Seward, perhaps still bitter after being denied the position of Attorney General. Seward secretly shared this belief, and due to that he endeavored to take matters upon his own hands, and snuffing Lincoln’s instructions, he proposed several solutions, including the disastrous Committee of Thirteen that only increased suspicion and fear within the Border South and was unable to prevent Virginia’s secession.

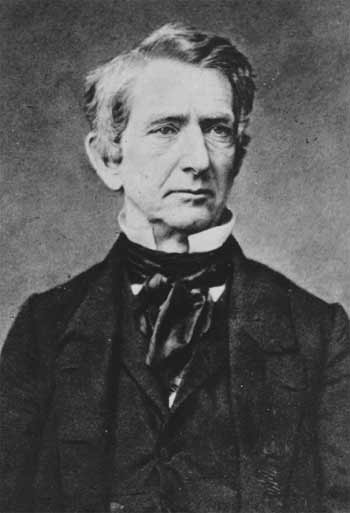

Secretary of State, William H. Seward

This later event so alarmed Seward that he went behind Lincoln’s back and promised to Virginia delegated that there would be no attempts to hold by force of arms Federal property, which they willfully interpreted as a pledge to evacuate the two forts still under Federal control: Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens. When Lincoln learned of this, he was backed into a corner for he could not publicly declare his intention of possessing and retaking Federal property without being seen as an aggressor.

Pressure from multiple fronts build up as many men looked up to Lincoln for guidance in that trying hour. “We elected Lincoln, and we are ready to fight for him if necessary”, declared an Illinoisan. From Ohio, a man said that “Lincoln must enforce the laws of the United States against rebellion, no matter the consequences”. Lincoln needed to appear as a firm leader. Despite his 6 successful years as a Senator, many still distrusted him and doubted the prairie lawyer who liked to tell funny stories would be the man of the hour.

This necessity to appear firm and in command made Lincoln more resistant than ever to Seward’s attempts at taking command. After an embarrassing incident when a threat of assassination forced Lincoln to sneak into Washington “like a thief of the night”, Lincoln wrote a polite but stern letter to Seward. Whatever the course the administration was to take, “I must decide it”, said the President. It’s undoubtable that the whole incident steered Lincoln towards not heeding Seward’s advice regarding his inaugural address. When Lincoln made clear his intent of defending Federal property, including the Forts, many Southerners felt betrayed, and that probably played a role in Virginia’s secession.

Later, when Lincoln actually assumed the Presidency, Seward still tried to take command by forcing Lincoln to not appoint Chase. “I can’t let Seward make the first move”, said Lincoln to his private secretary. Lincoln this time was firmer, arranging a private meeting with Seward and getting him to back down from this attempt to force Lincoln’s hand and also other projects such as declaring war on both Spain and France to supposedly unite the country. After that, Seward served as one of Lincoln’s most able and useful allies.

While Lincoln busied himself building a Cabinet, Confederate lawmakers close by at Richmond were trying to build a nation. A first convention had been scheduled to meet at Montgomery, Alabama, but switched places to Richmond, Virginia, soon after the secession of the Old Dominion. This was convenient for several Senators, who now despairing of the Union, were giving teary, solemn, or contemptuous goodbyes to their colleagues.

One of them was John Breckinridge of Kentucky, who fulfilling his promise of taking up a soldier’s musket if his country demanded it, resigned and went South. Breckinridge’s difficult decision had been taken when the Republicans almost unanimously rejected the Compromise he had so carefully crafted. If he couldn’t take the mantle of Clay, he would take the mantle of the Founders and fight for liberty, as he envisioned it. In Breckinridge’s mind, whether Lincoln would coerce or not the South was no longer a question. He had to decide, and he chose the South. Predicting a Civil War which would probably involve his state, he and several Democrats started working towards making Kentucky secede. Meanwhile, Breckinridge himself attended the Constitutional Convention.

Howell Cobb, President of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate Constitution Convention worked quickly and efficiently. Using the US constitution as a frame-work, they quickly drafted a Provisional Constitution. Most changes were related to state rights and the power of the Central government. Removing the “general welfare clause” and “a more perfect Union”, and adding "each State acting in its sovereign and independent character" after “We the People”, served as a way of claiming the true legacy of 1776. The Slave Trade was still forbidden despite some noise from the Lower South, this to calm the economic and social sensibilities of Virginia, North Carolina, and the not-yet seceded states, which were more moderate and depended on selling their slave surplus down South for extra revenue. The Constitution empowered states to impeach Confederate officials whose duties lay only in the state, and forbade a tariff to protect domestic industries or aid to internal improvements.

The powers of the executive were a matter of more interest. The President was weakened by being given just a single 6-year term, without re-election. Then he was strengthened with an item-line veto on appropriations. Members of the Cabinet would also have a non-voting seat in Congress. The matter of most interest, however, was who would be the President.

Several candidates were floated. Yancey and Rhett, some of the more prominent and famous original secessionists were seen as natural choices at first. But North Carolina and Virginia especially carried an enormous weight, and these two Upper South states plus Deep South moderates united to stop the Fire-Eaters. In their view, they shared the guilt of the painful separation with the blackest of Republicans.

Three Georgians seemed the next best option: Howell Cobb, Alexander Stephens, and Robert Toombs. The Georgia delegation could not unite behind one of them, and both Stephens and Toombs suffered handicaps that disqualified them. Stephens had resisted secession until the last minute, being a conditional unionist. Toombs was a former Whig and his temperament, including drunkenness, made him suspect. Moreover, the Upper South preferred one of their own, which they believed would help establish a moderate image before the world and the other Slave States. For this reason, and mindful that Jefferson Davis preferred a military command, the Convention turned to John Breckinridge.

A moderate Democrat, an experienced Senator, Buchanan’s Vice-president and an able statesman, Breckinridge was the chosen candidate of the Democratic Party in 1860, sweeping the South. Electing Breckinridge as President would help give legitimacy to the new government, and he was already popular in the South. Furthermore, he was from Kentucky, a state the new Confederacy had to secure. Protected by the Ohio, and with abundant horses and industry, Kentucky would be a valuable asset that would help push Tennessee, Missouri, and Arkansas into the Confederacy. Breckinridge would probably convince many that compromise was impossible, for if even he had joined the Confederacy there was no salvation for the Union. This last point caused some contention from people who suspected Breckinridge’s loyalties, but his prestige and experience pushed many to support him.

Though Breckinridge was only a reluctant secessionist, a sense of duty and destiny compelled him to accept the Convention’s call. To balance his administration, the Deep South Alexander Stephens was selected as Vice-president. A former Whig with more legislative experience, Stephens contrasted with the Democratic and Executive-oriented Breckinridge, while also complementing him as a fellow moderate. The Convention thus intended to emphasize that they were being forced to start a revolution, instead of rebelling by caprice as Lincoln had said. Besides, it constituted a gesture towards Georgia, which allowed Breckinridge to pass over the still bitter Toombs.

Breckinridge had recognized in Toombs a powerful ambition, which had driven him to not accept the vice-presidency. At first, he had considered appointing him as Secretary of State, but Breckinridge firmly believed that Confederate foreign policy would be one of the most important policies of the new nation. Thus, he appointed him instead to a position in the new Army of Virginia, which was being organized under the command of Robert E. Lee. This was enough for Toombs, who saw a military position as a better way of fulfilling his hunger for glory. For Secretary of State, Breckinridge instead chose Robert M. T. Hunter.

The position of Secretary of War was given to Jefferson Davis, who was an experienced soldier, a West Point graduate who had served with distinction in the Mexican War and later was chosen as Buchanan’s Secretary of War. He would have to work with General-in-chief Joseph E. Johnston. Johnston, another West Point graduate, had served for many years in the US Army, serving in the staff of Winfield Scott at Veracruz, and attaining the rank of Brigadier General. In 1860 he had been appointed US Quartermaster General. For his experience and seniority, Breckinridge decided to appoint him as General-in-chief of the new Confederacy, after having to fight with the Convention to even create such a position.

John C. Breckinridge, President of the Confederate States of America

Breckinridge and his new administration adopted mostly a position of inaction for the first weeks. As a Kentuckian, he recognized that the Border South had conflicting loyalties. If the Confederacy acted as the aggressor, moderates and the people still on the face would be pushed towards Unionism. The need to appear firm pushed him towards some bellicose first speeches, declaring that the South was ready to defend themselves from Yankee aggression with cannon, powder, and shot; but most of his speeches and declarations were more peaceful, emphasizing that the South only wanted to be left alone, to go on peace.

This “go on peace” approach was favored by some Yankees. Coercion would inevitably start a Civil War, so they didn’t saw it as an option. If the South was allowed to secede, either secession fever would run its course and they would return to the Union, or the catastrophe of war would be averted. But this position commanded little support, since many, Lincoln included, saw that as the start of the unraveling of the United States: if the rebel states were allowed to secede without consequences, they would be repudiating the supremacy of democracy and of the National government, and soon many more would join them in rebellion.

Others demanded blood. “Have we got a government!?”, exclaimed exasperated newspapers that wanted action, and wanted it now. The Lincoln administration, they said, was comatose and useless. A point of special worry was how the National capital was now wedged between a seceded state (Virginia) and a slave state (Maryland). Lincoln could not give up Washington, but calling for the necessary troops to defend it would be seen as coercion.

Breckinridge faced similar problems. “The ardor of the people is cooling off”, warned a Louisianan. “If we want this revolution to triumph”, added a Virginian, “we must demonstrate our intent to stand firm before the Washington tyrant.” These demands had pushed Breckinridge towards allowing the organization of an army, approving the enlistments of one-year volunteers, and the creation of two armies: The Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Robert E. Lee, and the First Confederate Army, under the command of P. T. G. Beauregard.

Beauregard’s volunteers had become Southern heroes by forcing the surrender of Forts Moultrie and Sumter, in the final days of the Buchanan administration and the first days of Lincoln’s. Major Robert Anderson, the commander of Fort Moultrie, had moved his troops from this outdated fort to the powerful and modern, if undermanned, Fort Sumter. The South interpreted this as a betrayal in Buchanan’s part, who had promised to not change the military situation around the Forts for the time being. Succumbing to Southern pressure and desperate to avoid a Civil War before Lincoln took over, Buchanan ordered Anderson back to Fort Moultrie. There, Confederate cannons obtained thanks to former Secretary of War John Floyd allowed Beauregard to threaten Anderson, and prevent him from moving back to Sumter. Lincoln tried to organize a rescue mission, but he lacked the resources. General in-chief Winfield Scott was advising against such an attempt, for it would be seen as an act of aggression, and the Army’s resources had to be concentrated around Washington.

When a single, unarmed ship approached, Beauregard drove it away and bombarded Fort Moultrie, thus obtaining Anderson’s surrender. The Confederate flag rose above both Forts, Lincoln unable to do anything. This was a fatal blow against his new administration.

But Lincoln’s focus and that of the nation turned to Richmond, where an attack was being supposedly organized by the rebels. Breckinridge had no intention to start a war, but the widespread opinion through Washington and the entire Union was that the rebels were coming. To evacuate Washington without a fight would completely destroy Lincoln’s government before it had even started, especially after the humiliation of Fort Moultrie. Considering this, Lincoln decided that he had no option, and ordered Scott to prepare to defend the capital no matter what. The President made it clear that he had no intention to attack Richmond or start a war, but that in the face of Confederate aggression he had no option.

The Union cheered the decision. “The President has shown that he has the power and the intention to govern”, said a Massachusetts man. “As long as the sacred capital of the greatest government on earth stands, I shall not despair of our glorious Union”, added a Pennsylvanian. Horace Greeley congratulated Lincoln for “showing firmness before the aggression of the Slavocracy.” Indeed, for many this was the first sign that the Lincoln administration, hitherto comatose, intended to do something. “The Federal government has been assailed”, a supporter wrote to Lincoln, “it’s your duty to defend it, and me and millions more expect you to fulfill it.”

But the South didn’t see this as a defensive act, but an aggressive one. Rumors started to circulate widely that the North intended to build up an Army and march South. The Panic was greatest in Baltimore, where some regiments of the regular army were finally arriving from the west to protect the Capital. Anti-Union riots started and culminated with Washington isolated, the railways that connected it with other cities destroyed, and its telegraph lines cut. And from the South, an Army was reportedly coming.

A desolate and forlorn Lincoln stared out the windows of the White House while General Scott desperately organized clerks and shop owners into militia for a desperate last stand. For all he knew, Lincoln would be the last President of the United States. But from every corner of the North echoed a call, as thousands vowed to fight their way to Washington and save the nation