Looking forwards to the update then. And I suppose that such "narrow scope" updates are a good way to get in all the detail you want. I'm liking the depth of this TL.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"wasn't she wearing a brand New Jersey?What’s a Delaware?

You know I just remembered one of my favorite ironies of all time. The fact the Confederate Constitution made Secession illegal.

Did it?

There's actually...no express reference to the right (or lack of right) of a state to secede anywhere in the text.

I think the basis for this belief originates in an episode that occurred in the Confederate Senate in 1863, when the Senate heard a proposed amendment to the Confederate Constitution that would allow an aggrieved state to secede from the Confederacy. The fact of such a proposal seemed suggestive to some observers down through the years that there was a lack of such a right that needed to be remedied.

"It was proposed that the new [Confederate] Constitution explicitly recognize the right of secession, but the idea was dropped after others suggested that 'its inclusion would discredit the claim that the right had been inherent under the old government.' [Wilfred B.] Yearns, [The Confederate Congress (1960)], at 29; see also [Charles Robert] Lee [Jr., The Confederate Constitutions (1963)], at 101-02 (citing the relevant portions of the Journal and arguing that the right to secede was 'implied in the specific phraseology of the Preamble,' which in what seems to me a less than conclusive manner declared that the Constitution was the work of 'the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character' . . .)."

David P. Currie, Through the Looking Glass: The Confederate Constitution in Congress, 1861 - 1865, fn. 39.

It sure would be interesting to see what would have happened had some state ever tested it. Of course, you'd need a Confederate Supreme Court to adjudicate it; the CSA never got around to forming one during the war.

In these updates can they not jump around too much time wise like have it been in one year or couple months then frame?

Let me explain. In OTL, a lot happened in 1862. McClellan launched the Peninsula campaign and was driven back, with Lee pursuing and winning at Second Manassas before being turned back at Antietam. At the same time, Bragg invaded Kentucky. At the same time, Grant was getting ready for his Vicksburg campaign and Buell was sluggingly advancing towards Kentucky. At the same time, Lincoln was mulling over the slavery question, with several important social developments regarding slavery that would push him towards the Emancipation Proclamation. Politically, Congress passed many acts dealing with the economy, industry, taxes, and conscription; and the 1862 midterms approached. All this took place in 1862, yet I can't cram it all in a single update. Assuming everything goes the same (it won't), I'd divide 1862 into several updates: one for the Peninsula, one for the invasion of Maryland, one for Kentucky, one for the social issues, one for the political issues. All the 1862 updates would be one after the other, and follow a single "storyline" so to speak. Not jumping around wildly from 1862 to 1865 or anything. Now, side updates will be more general. If I write a side update about technology or medicine, for example, it would probably cover the entire war. That's why they're outside the main updates.

This means that right now that secession is taking place, a lot of stuff is happening at the same time in a short frame, and I will divide it as follows: one update for social issues that pushed the South towards secession and the initial steps; political organization of the Confederate government and the Lincoln administration; opinion of war, preparations, state of the Confederate and Union militaries, and the outbreak of war; the first months of war.

Awesome!

What's Lincoln's cabinet going to look like? I'd like to see Thaddeus Stevens get a cabinet position

That's interesting, but I'd prefer Stevens to remain in the House as a radical leader.

Did it?

There's actually...no express reference to the right (or lack of right) of a state to secede anywhere in the text.

I think the basis for this belief originates in an episode that occurred in the Confederate Senate in 1863, when the Senate heard a proposed amendment to the Confederate Constitution that would allow an aggrieved state to secede from the Confederacy. The fact of such a proposal seemed suggestive to some observers down through the years that there was a lack of such a right that needed to be remedied.

"It was proposed that the new [Confederate] Constitution explicitly recognize the right of secession, but the idea was dropped after others suggested that 'its inclusion would discredit the claim that the right had been inherent under the old government.' [Wilfred B.] Yearns, [The Confederate Congress (1960)], at 29; see also [Charles Robert] Lee [Jr., The Confederate Constitutions (1963)], at 101-02 (citing the relevant portions of the Journal and arguing that the right to secede was 'implied in the specific phraseology of the Preamble,' which in what seems to me a less than conclusive manner declared that the Constitution was the work of 'the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character' . . .)."

David P. Currie, Through the Looking Glass: The Confederate Constitution in Congress, 1861 - 1865, fn. 39.

It sure would be interesting to see what would have happened had some state ever tested it. Of course, you'd need a Confederate Supreme Court to adjudicate it; the CSA never got around to forming one during the war.

Still, this episode reveals an ironic contradiction within the Confederate government, and indeed most revolutions. In order to keep the revolution alive, the revolutionaries often have to take measures that contradict the very principles upon which the revolution was begun. The Confederates fought for slavery and for a Jeffersonian view of the US: a small government that has no power over the citizens and powerful states rights (rights to own slaves, that is). Yet they were forced to adopt Hamiltonian measures several times, such as conscription, martial law, the suspension of Habeas Corpus... Many denounced these steps as tyrannical movements that contradicted all the Confederacy was fighting for.

Many denounced these steps as tyrannical movements that contradicted all the Confederacy was fighting for.

In fact, it sent Davis's own vice president (Alexander Stephens) off to sulk back at his home for most of the war!

But as you say, revolutions often have to traffic in hypocrisies to survive. The CSA ironically imposed conscription before the USA did.

Of course, the shoe was on the other foot, too, a few times: Lincoln the lawyer held the right to habeas corpus in high esteem; but he was quick to suspend it himself when he thought it was vital to the war effort.

The real test for the CSA would have come if a state HAD decided to secede. It would be one of the most spectacular hypocritical acts in human history had Richmond decided to resist it; but if they allowed it, they could see it begin a chain reaction of dissolution that could leave them all open to Yankee reabsorbtion.

Last edited:

The real test for the CSA would have come if a state HAD decided to secede. It would be one of the most spectacular hypocritical acts in human history had Richmond decided to resist it; but if they allowed it, they could see it begin a chain reaction of dissolution that could leave them all open to Yankee reabsorbtion.

It was a lose-lose situation. Either they forbid it and they look like hypocrites and add further credence that it really was about slavery or allow it and they'd eventually dissolve into various states distrusting one another and the Union can pick them off one by one. Hell, maybe even the CSA just dissolves into anarchy or neo-feudalism and the the Union can administer them as territories.

Chapter 11: The Counterrevolution of 1861

Chapter 11: The Counterrevolution of 1861

Thousands would forever remember that balmy Monday of 1860, when the tensions, fear, hostility and ambitions of the past decade were finally left out in a cathartic spectacle of fireworks, parades and fiery rhetoric. Moderates looked on apprehensively while secessionists stood proudly in Columbia, South Carolina, amid immense displays of popular excitement. Palmetto flags waved in the air, and bands poured patriotic music. Cannons and rifles sounded through the air, a martial call that echoed throughout the city. Militia marched, shouting and singing excitedly. Some even were calling themselves “Minutemen”. Dancing women with flowing skirts and flag-waving children completed the celebration of South Carolina’s secession.

Indeed, a state convention, called by the Legislature even before Lincoln’s election supposedly to answer to the threat of a slave uprising, had just voted unanimously to secede from the Union on November 25th, 1860. “Nothing on earth shall ever induce us to submit to any union with the brutal, bigoted blackguards of the New England States!", declared these revolutionaries. Such statements, reflecting defiance or uncertainty, were commonly heard ever since Lincoln was elected. Mary Boykin Chesnut remembered a man who despondently said “Now that the black radical Republicans have the power, I suppose they will Brown us all” immediately after hearing of Lincoln’s triumph. Others were overjoyed by the same news, William L. Yancey among them.

A known fire-eater, Yancey had worked tirelessly for Southern secession for years. He wrote the famous Alabama platform at the 1848 Democratic National Convention, which demanded support for slavery from any National Candidate. When his platform was rejected, Yancey walked out, joined only by a single delegate. The Alabamian would remain out of the party for 7 years, returning in 1855. Declaring that he would “endeavor to be entirely conciliatory” because that “gains the ears of the opposition and opens the way to their hearts”, Yancey set out to work, acting as a moderate so that he could slowly push real moderates towards the edge. From there only a small tremor was needed to plunge the South into secession, and Lincoln’s election had been more than that – it had been an earthquake.

The North had overwhelmingly thrown its support behind a Black Republican, rejecting Bell and Breckinridge, two moderate, conservative men. Yancey had supported Breckinridge during the nomination process, and most of the Deep South followed him. By the time of the Democratic National Convention, the Democratic Party had become a thoroughly Southern Party, and thus the contest was at first between Deep South men who supported Senator Hunter of Virginia, and Upper South delegates who preferred Breckinridge. Ultimately, the convention settled on moderation, choosing Breckinridge and demanding only Federal protection for slavery on the territories, not other outrageous demands such as conquering Cuba or repealing Personal Liberty Laws. But this moderate ploy played right into the hands of radicals and fire-eaters. If the North rejected even the most moderate man of the South, then many would come to their side and accept secession as necessary. The dominoes were set.

Then when Lincoln was elected by a landslide, the dominos were set in motion by South Carolina’s actions. Before Christmas, similar resolutions were adopted by Mississippi and Alabama. After the New Year, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana and Texas had seceded as well, Texas being the last to secede in January 23rd. The average vote in favor of secession was 90%.

South Carolina secedes from the Union

South Carolina had acted so promptly because they feared that previous cooperation would dissolve into inaction. Previous attempts at secession and cooperation between the Cotton states had ended in fiascos. A state legislator expressed that South Carolina “must make the move & force them to follow. This is the way of all revolutions & all great achievements.” Another faction known as cooperationists asked them to wait. Though they were accused of disloyalty, they were ardent supporters of Southern Rights – what they were against was reckless action. They wanted to first have a convention of southern states, then a united South could go out of the Union in a stronger position. But by daring to go out first, South Carolina provoked an avalanche as an emergency mentality set off over the Deep South.

This mentality demanded swift action. We must “cut loose” from the Union “through fire and blood if necessary, less our foes get access to our negroes to advise poison and the torch”, said an Alabamian. Cooperation between Southern states could come later after secession was a fait accompli. And thus, the fire-eaters swept the cooperationists along with them. A Georgia cooperationist admitted that three states “have already seceded... In order to act with them, we must secede with them." Louisiana’s Judah P. Benjamin, who considered himself a prudent man and opposed immediate secession, still joined this Southern revolution when his state went out. He ruefully regretted that the “conservative men of the South” were not "able to stem the wild torrent of passion which is carrying everything before it… It is a revolution… of the most intense character… and it can no more be checked by human effort, for the time, than a prairie fire by a gardener's watering pot.”

Other faction was the conditional unionists, who wanted to draw a list of demands for the Lincoln administration, or wait until he committed some sort of “overt act” against Southern rights before seceding. This position was ridiculed by many. The Charleston Mercury thundered that “although you see your enemy load his rifle with the direct purpose of taking your life, you are to wait... until he shoots you.” Congressman James L. Orr declared that the protection of the South’s “honor and safety… will require prompt secession.” “After the Lincoln party is elected… you will be called to show your love by preparing your rifles”, added Yancey. "We will go for revolution, and if you… oppose us… we will brand you as traitors, and chop off your heads", warned a Georgia secessionist.

They were exposing a common-held view throughout the South: the election of Lincoln could already be considered an overt act. They must not give Lincoln any chance to prove his moderate tendencies, for even if Lincoln himself didn’t act, the influence of his victory would plunge the South into ruin. South Carolina’s J. Foster Marshall declared that “the poisoning and murdering of [South Carolina’s] men, women, and children will be contemplated after Lincoln takes the helm… If the Abolitionists can thus destroy our property and excite our people by merely sending their agents and money in our midst, what can they not do when they take control of the legislative and executive branches?” “What mischief may you... expect when Lincoln gets into power, even if they do not legislate at all?”, asked a North Carolina fire-eater.

Hate against Lincoln and his party was extremely strong. Previous to the election, newspapers declared that every vote cast for a Republican was a cold-blooded insult against the South. A Mississippi man denounced Lincoln as a “wretched backwoodsman,” with “cleverness indeed but no cultivation.” Lawrence Keitt’s wife called the Black Republicans “a motley throng of Sans culottes and Dame des Halles, Infidels, and freelovers, interspersed by Bloomer women, fugitive slaves, and [racial] amalgamationists.”

Similar statements can easily be found. The South could not submit to Republican rule, because that would create a dangerous precedent that would allow the Black Republicans to destroy them eventually. “The South must either secede,” said the British consul in Charleston, “or expose herself to the ridicule of the world.” Moreover, many more feared that Lincoln was nothing but the first step to something worse. As President, he could appoint thousands of Federal officers, thus building a Southern Republican Party. This strategy had been championed by the Blairs of Missouri, who, through German Protestant support, had managed to elected a Republican congressman from that slave state. Hinton Rowan Helper, in his book “The Impeding Crisis of the South” had said that non-slaveholding whites could be swayed by anti-slavery rhetoric. The Governor of Georgia concurred that the allurement of office could draw many to “treachery against their section”. Yancey shared his fear: “There is no denying that there is a large emancipating interest in Virginia and Kentucky and Maryland and Missouri.” If the South didn’t act soon, a Southern Republican Party would be born and eventually these Yankee brigands would be able to set the Negroes free.

South Carolina’s secession ignited a fire that spread throughout the entire Deep South very quickly. But the Upper South proved more resistant to this wildfire. Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas and North Carolina organized referendums on whether there should be a convention at all. All states approved conventions, some only barely such as North Carolina and Tennessee, where the secessionists only triumphed by 4% and 1% respectively. In almost all these states Unionists had a 2/3 majority. But unlike what Lincoln and many Northerners hoped, these Unionists were conditional ones. For some of them, the North had already destroyed the Union by electing Lincoln. For others, any “overt act” would be enough to push them into secession. Kentucky, Missouri and Maryland all declined conventions; Delaware hadn’t even considered one. The other states voted against secession, but their conventions remained open to watch all future developments. All seemed to be firmly in the Union camp for the time being, except for one.

The exception was Virginia. The South’s most populated and richest state had been driven into a frenzy due to John Brown. The ghost of the abolitionist still plagued them when Lincoln was elected. Before that, many measures were taken. For one, the Legislature amended the Constitution, allowing Governors to serve two consecutive terms, which gave way for the re-election of the secessionist Henry Wise. Furthermore, they proceeded to gerrymander mountainous West Virginia, an area usually hostile to slavery. When a convention was called, the gerrymander remained in place, allowing secessionists to take almost half of the convention. The convention still voted against secession, but only barely. Instead, the conditional unionist majority called for a Congressional Committee to be organized and solve the crisis.

This Committee of 13 was composed of powerful men such as Seward, Toombs, Davis, Crittenden, Vice-president Breckinridge, and President-elect Lincoln. Breckinridge and Crittenden, both from Kentucky, tried to take the mantle of Henry Clay and craft a compromise. But the final compromise amounted to little more than an unconditional surrender from the North: slavery was to be allowed and protected in all territories held or acquired after the compromise, slavery could never be abolished in the District of Columbia or Federal properties, and the Federal government was stripped of all power to interfere with slavery in the states.

Lincoln and Seward decried these measures immediately. They wanted to save the Union, but such a dishonorable surrender would be a repudiation of the majority that had just voted for them. It would motivate filibusters, who would “invade every nation holding a foot of land in the Americas”, and destroy all the hard-earned fruits of the 1860 election. Lincoln declared that this compromise "acknowledges that slavery has equal rights with liberty, and surrenders all we have contended for… We have just carried an election on principles fairly stated to the people. Now we are told in advance, the government shall be broken up, unless we surrender to those we have beaten… If we surrender, it is the end of us. They will repeat the experiment upon us ad libitum. A year will not pass, till we shall have to take Cuba as a condition upon which they will stay in the Union."

Southern Senators despaired. Crittenden attempted to put the compromise to a vote in the Senate, which failed due to united Republican opposition. The House also rejected it, adding some fiery and vengeful speeches for good measure. The Republicans "swore by everything in the Heavens above and the Earth beneath that they would convert the rebel States into a wilderness”, reported a National Union Representative. From the Midwest, many threatened to “blot Louisiana out of the map” if the rebels dared to prevent them from accessing the Mississippi. The stakes rose higher when a report came from Kansas: free-soil militia and border ruffians had clashed again, and the Topeka legislature had just declared itself the legitimate government, anticipating treason from the Lecompton legislature. From Ohio and Illinois came reports of Wide-Awake militias, marching and drilling. Lincoln also announced that he would do his duty and “put down treason” by force of arms if necessary, also ordering General in-chief Winfield Scott to stand ready to defend or reclaim Federal property.

The Virginia Convention

This pushed nerves in Virginia to the breaking point. Lincoln and his army of John Browns intended to coerce the South. Would Virginia stand with her sister states or aid in their destruction? Passions flamed in the Old Dominion as the Conditional Unionists changed opinion and endorsed secession. Directed by Wise, militia began to seize armories and shipyards, capturing Norfolk and Harpers Ferry. Virginia had not seceded officially yet, but mobs in Richmond and other cities threatened armed revolution if a political one was not effectuated soon. Pushed by popular fears and pressure, and galvanized by an attempt to impeach President Buchanan, Virginia seceded in February 15th.

Buchanan and Lincoln could not see eye to eye on many issues, but they agreed that secession was unconstitutional. The President took a stump to deliver a passionate speech against treason. “The Union is not a mere voluntary association of States, to be dissolved at pleasure by any one of the contracting parties," he declared, warning that the Constitution was the supreme law of the land, and that National sovereignty trumped the state sovereignty the South professed to defend. But he also declared that he had no power to coerce the states back into the Union.

The Republicans denounced this position. “The President has the obligation to enforce the law until someone opposes him”, said Seward in a sardonic reply. Lincoln, on the other hand, considered that the President has “the power, the right, and the obligation to enforce the supremacy of the National government”. Outraged Congressional Republicans demanded explanations, especially after Secretary of War John Floyd was allowed to resign despite his acts of corruption and his order to send cannons and arms down South. Congress, now under complete Republican control due to the resignations of several Southern Senators and Representatives, asked Buchanan to send troops to Virginia to capture Floyd, who had declared himself a secessionist. Buchanan refused.

“The President has approved of treason”, declared Salmon P. Chase. Charles Sumner agreed. “This old hireling of tyrants and slavers has now again sided with the Slave Power over his country”. In the House, a furious Thaddeus Stevens asserted that Buchanan “had failed every man of this great Republic” with his refusal to “commit to his constitutional obligations and protect our government”. If Buchanan refused to enforce the law and allow the South to go out of the Union, the government would be destroyed. One of the principles of democracy was that the minority has to accept the electoral victory of the majority. With almost 50% of the nationwide popular vote, Lincoln had a clear mandate. If the South didn’t recognize it, and their treason wasn’t stopped, the US would soon descend into “many petty republics” fighting between themselves, for every state would secede as soon as they lost an election. The power of the Federal government had to be enforced, and to do that Buchanan had to be taken out of the way. Thus, the House decided to impeach him.

The resignation of the representatives of these Deep South states had given House Republicans a thin supermajority. The motion to impeach Buchanan and Breckinridge was introduced in late January, and it came to a vote in early February. There wasn't enough time to actually remove both officials; rather the main idea was exercising pressure on the President and force him to act against treason. Conservative Republicans managed to prevent it from passing, but this attempt was seen as the “overt act” many Conditional Unionists were waiting for. “A coup against the government has taken place”, Wise asserted, “can you not see the dangers of remaining in the Union?”. The convention saw these dangers, and voted for secession.

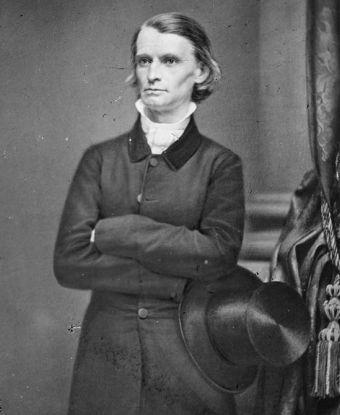

Henry A. Wise

North Carolina was next. They had also organized regiments of militia, and allowed the troops of other states to enter. Their convention had remained open, and now the 2/3rds majority of conditional unionists were ready to risk disunion. The status and prestige of Virginia convinced many that waiting or adopting neutrality was no longer possible in light of Lincoln’s approaching inauguration and the fact that North Carolina was in the middle of two seceded states. Her governor, John Ellis, said in a speech that he “could not be part of the violation of the country’s laws, and the repudiation of its principles by a radical faction”. In March 15th, 11 days after Lincoln’s inauguration, North Carolina seceded from the Union.

Lincoln’s inaugural speech probably played a part, for the President pledged to “use all the powers” under his disposal to "reclaim the public property and places which have fallen; to hold, occupy, and possess these, and all other property and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties on imports." The South interpreted this pledge as deadly coercion, and vowed to never submit to his rule.

The whole debacle also propelled Kentucky, Missouri and Maryland into calling for conventions, which remained open alongside Tennessee’s and Arkansas'. Tennessee, Arkansas and Kentucky passed resolutions declaring their neutrality, unless the incoming government attempted to force them into war. Similar resolutions were barely defeated in Maryland, Kansas and Missouri. The tide of revolution continued, as thousands of Southerners rallied to their flag to defend their homes, their families, and white supremacy.

Much secessionist rhetoric played variations on this theme. The election of Lincoln, declared an Alabama newspaper, "shows that the North [intends] to free the negroes and force amalgamation between them and the children of the poor men of the South." “Do you love your mother, your wife, your sister, your daughter?" a Georgia secessionist asked non-slaveholders. If Georgia remained in a Union "ruled by Lincoln and his crew… in ten years or less our children will be the slaves of negroes." "If you are tame enough to submit," declaimed South Carolina's Baptist clergyman James Furman, "Abolition preachers will be at hand to consummate the marriage of your daughters to black husbands." No! No! came an answering shout from Alabama. "Submit to have our wives and daughters choose between death and gratifying the hellish lust of the negro!! . . . Better ten thousand deaths than submission to Black Republicanism.”

These revolutionaries could be better characterized as counterrevolutionaries. Pre-emptive ones to be exact. Counterrevolutionaries seek to restore the ancien regime, or to prevent its fall in the first place by acting before a revolution could take place, or before it could be consolidated. Jefferson Davis insisted that they were not revolutionaries, but conservatives, while Southern newspapers claimed that they had been forced to act against a radical revolution. Southerners fought for the principles of ‘76, as they understood them: freedom from a coercive national government, and freedom to own slaves.

Northerners disagreed. To assert that the South fought for the same cause as the Founding Fathers was libel. Washington, Jefferson, Franklin and Adams had fought for liberty, for self-determination and the rights of man. The South was fighting for despotism and slavery. This last point perplexed many who simply didn’t understand why poor whites would join the slavers in rebellion. Some rationalized that there was a silent Unionist majority, but the answer is that white supremacy also benefitted poor whites, who felt secure because there would always be someone under them. "Among us the poor white laborer . . . does not belong to the menial class. The negro is in no sense his equal… He belongs to the only true aristocracy, the race of white men”, said Governor Brown of Georgia.

For these principles, and under these circumstances, secession took place in the winter of 1860-1861. Lincoln assumed office in March 4th, 1861. The new president had an enormous weight thrown on his shoulders. The country seemed to be disintegrating around him, and rebellion threatened to overwhelm the government. Lincoln had reached a pivotal point, and now he needed to choose what to do. With conventions still open in several states, and many of them ready to join the new Confederate States of America, action was needed. But what could Lincoln do to save the country?

The situation in March, 1861

__________________________________________________________________________________

AN: The title "The Counterrevolution of 1861", is taken from the title to one of the chapters of McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom. All credit goes to McPherson.

Last edited:

Five bucks it would be Texas that seceded from the Confederacy.The real test for the CSA would have come if a state HAD decided to secede. It would be one of the most spectacular hypocritical acts in human history had Richmond decided to resist it; but if they allowed it, they could see it begin a chain reaction of dissolution that could leave them all open to Yankee reabsorbtion.

After what's going on, I doubt the Democrat party survives if the Union wins. The Republicans should be the only party on the scene until Horace Greeley forms a "Liberal Party" as he almost did in 1872 OTL

Five bucks it would be Texas that seceded from the Confederacy.

I won't take that bet, Tex.

Didn't Arkansas secede from the union? Also, will we see a West Virginia secession from the confredncy becasue if not they have a base to attack Ohio

It did, but only after Sumter.

In OTL, Arkansas, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina were all in the second wave of secessions, after Sumter was over.

Yes but in this timeline akranas sececed after north caronlina but on the map it shows it in fluxIt did, but only after Sumter.

In OTL, Arkansas, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina were all in the second wave of secessions, after Sumter was over.

After what's going on, I doubt the Democrat party survives if the Union wins. The Republicans should be the only party on the scene until Horace Greeley forms a "Liberal Party" as he almost did in 1872 OTL

It's already all but dead. The war and cooperheadism msy give them a boost but they will probably dissapear after the war as you say.

Yes but in this timeline akranas sececed after north caronlina but on the map it shows it in flux

Yeah. I originally wrote that Arkansas had seceded but then corrected it before I saw your comment.

Yes but in this timeline akranas sececed after north caronlina but on the map it shows it in flux

Well, obviously Red has these two states being affected differently by his butterflies...

There was, in fact, a good deal of resistance to the idea of secession in both Arkansas and North Carolina before Fort Sumter (and more to the point, Lincoln's call for volunteers). Arkansas convened a secession convention in February, but most of the delegates were Unionist in sympathy. Even after militia had seized the Little Rock arsenal, the delegates were still unwilling to vote to secede. Only Lincoln's call moved them off the ball.

North Carolina is in a different situation, as Red points out, because once Virginia secedes, it's sandwiched between two Confederate states (states it has a good deal of sympathy and affinity for), basically cut off from the Union. I don't think this is an implausible development. If you can get Virginia to go, it's a lot easier to get North Carolina to go, too.

As he @Red_Galiray said it originally said that Arkansas seceded after North Carolina but he edited that and have just north Carolina seceded so...Well, obviously Red has these two states being affected differently by his butterflies...

There was, in fact, a good deal of resistance to the idea of secession in both Arkansas and North Carolina before Fort Sumter (and more to the point, Lincoln's call for volunteers). Arkansas convened a secession convention in February, but most of the delegates were Unionist in sympathy. Even after militia had seized the Little Rock arsenal, the delegates were still unwilling to vote to secede. Only Lincoln's call moved them off the ball.

North Carolina is in a different situation, as Red points out, because once Virginia secedes, it's sandwiched between two Confederate states (states it has a good deal of sympathy and affinity for), basically cut off from the Union. I don't think this is an implausible development. If you can get Virginia to go, it's a lot easier to get North Carolina to go, too.

Fascinating update. You did some homework on that.

1) Re: Virginia:

This is a slick move, and it definitely gets Virginia closer to secession. Wise was much more "secesh" than Fletcher, and that's a big difference right there. A lot of folks out in Western Virginia are gonna be unhappy with the rest, though...

2) Re: Lincoln:

Firstly, the order to Scott is almost certainly an error here, isn't it? Lincoln will have no authority over Winfield Scott until March 4. He can't order him to do anything - and it is hard to imagine Lincoln trying to seize that authority, even as a moral exhortation.

Secondly: It is hard to understate what an enormous step it is for Lincoln to publicly talk about "put[ing] down treason" by force of arms at this point in time. You're damned right Virginia would secede within hours. Hell, even Kentucky might go over the dam.

This would be a volcanic act in the Border States. It was Lincoln's call for volunteers in OTL to "suppress" the secessionists that cost him four border states (and effective neutrality by the Missouri and Kentucky governments).

The thing is, Lincoln would know it - he knew Kentucky and Missouri well enough, at any rate - and that is why he went into stealth mode in OTL until his inauguration, refusing to say much of anything at all.

I suppose what I am saying is that I am a little reluctant to readily accept even a more radicalized Lincoln taking such a momentous step before the outbreak of hostilities. He still has the same temperament, still has much the same fund of knowledge. He might be more keen for a confrontation now, but he would still be eager to keep as much of the Border state population onside (or at least, neutral) as possible.

Seward, by the way, would almost certainly have a stroke.

1) Re: Virginia:

Before that, many measures were taken. For one, the Legislature amended the Constitution, allowing Governors to serve two consecutive terms, which gave way for the re-election of the secessionist Henry Wise. Furthermore, they proceeded to gerrymander mountainous West Virginia, an area usually hostile to slavery. When a convention was called, the gerrymander remained in place, allowing secessionists to take almost half of the convention.

This is a slick move, and it definitely gets Virginia closer to secession. Wise was much more "secesh" than Fletcher, and that's a big difference right there. A lot of folks out in Western Virginia are gonna be unhappy with the rest, though...

2) Re: Lincoln:

Lincoln also announced that he would do his duty and “put down treason” by force of arms if necessary, also ordering General in-chief Winfield Scott to stand ready to defend or reclaim Federal property.

Firstly, the order to Scott is almost certainly an error here, isn't it? Lincoln will have no authority over Winfield Scott until March 4. He can't order him to do anything - and it is hard to imagine Lincoln trying to seize that authority, even as a moral exhortation.

Secondly: It is hard to understate what an enormous step it is for Lincoln to publicly talk about "put[ing] down treason" by force of arms at this point in time. You're damned right Virginia would secede within hours. Hell, even Kentucky might go over the dam.

This would be a volcanic act in the Border States. It was Lincoln's call for volunteers in OTL to "suppress" the secessionists that cost him four border states (and effective neutrality by the Missouri and Kentucky governments).

The thing is, Lincoln would know it - he knew Kentucky and Missouri well enough, at any rate - and that is why he went into stealth mode in OTL until his inauguration, refusing to say much of anything at all.

I suppose what I am saying is that I am a little reluctant to readily accept even a more radicalized Lincoln taking such a momentous step before the outbreak of hostilities. He still has the same temperament, still has much the same fund of knowledge. He might be more keen for a confrontation now, but he would still be eager to keep as much of the Border state population onside (or at least, neutral) as possible.

Seward, by the way, would almost certainly have a stroke.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: