Absolutely nothing went wrong the last time a French general was exiled to Elba. I mean, what could have gone wrong? Him coming back to lead the French army?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Popular Will: Reformism, Radicalism, Republicanism & Unionism in Britain 1815-1960

- Thread starter President Conor

- Start date

This one might come back for a little longer than 100 days... 😆Absolutely nothing went wrong the last time a French general was exiled to Elba. I mean, what could have gone wrong? Him coming back to lead the French army?

Hi guys, just a quick update on this. I realised while completing the next two updates (which will drop today) that I had uploaded an old version of the 1892 US Election update. I have replaced this with the new version. The only changes to the timeline are the existence of the National Portrait Gallery straw poll of the contingent election to give guidance to the financial markets on the next US President, meaning that by the time the next update takes place, it is known that the incoming administration is President-elect Cleveland, alleviating any financial uncertainty. All will become clear - apologies for this oversight, obviously I have a lot of updates versions flying around and this is obviously a sign I need to organize them a bit better!

Part 5, Chapter XL

V, XL: All to the French!

The annals of history turned a significant leaf when on the clandestine night of October 12th, 1892, under the veil of darkness, a band of fervent Algerian French Arabs, self-styled the “Insurrectionary Communal Militia of Algiers,” dared the impossible.The mission was perilous, the Royalist dragnet was tightening yet, under the shroud of secrecy, the group rescued Boulanger from the jaws of despair. In a daring mission, the group collected a wax print of the key, swiped from a priest in the jail he was interned in, buried outside the prison by sympathetic local Actionists. Boulanger didn’t run, but walked through the front door of the prison. The group even had time to telegram the leadership in Toulouse with a simple message “Augustus is free.”

As whispers of Boulanger's escape coursed through the veins of France, the nation's pulse quickened. Finally, the Toulon Committee announced to euphoria across the South that the vessel Boulanger boarded had contacted the commune to “prepare the city for the return of the Généralissime to France.” The saga of his escape was recounted in hushed tones, and then in bold declarations across the nation, spurring imaginations, igniting the spirit of resistance.

The mood was summed up in a newspaper article speculating on the escape, saying, "The tales of Généralissime's escape are the bards' songs of our time. His name resounds through the factories and fields, a beacon of courage in the looming darkness. We see in Boulanger not merely a man, but a symbol of our indomitable spirit. His narrative is now etched in the annals of our struggle, a tale of defiance against tyranny, a promise of a dawn awaiting beyond the night's tyranny. His sacrifice and the sacrifice of the Frenchmen from Algeria motivates us to keep going, keep pushing for the victory over the politicians and the so-called King."

During his rescue, the Généralissime was extremely grateful to his rescuers, further developed, and deepened his understanding of the symbiotic bond between the metropole and the colonial territories. As he set foot on friendly soil, welcomed by both continental and colonial compatriots, the vision of a Francophone realm united by commonality and unity of belief crystallized before him.

The collective endeavour that fuelled his liberation became emblematic of the potential synergy that could flourish under a shared flag and common cause. Through numerous dialogues with his diverse cadre of rescuers and supporters, who represented a microcosm of the broader Francophone spectrum, Boulanger’s convictions matured. The mosaic of cultures, backgrounds, and shared fervour for a unified Francophone identity resonated deeply with Boulanger, he wrote in a letter upon his return.

The City of Toulon, 1890, site of the return of Boulanger

The revelation that the strength of the French ethos was not confined to the borders of the mainland, but vibrantly echoed across continents in the hearts of all French speakers, birthed a renewed vigour within him. His ideologies evolved to embody a more inclusive, global vision of French identity, transcending geographical and racial divides. This epiphany further galvanized Boulanger's resolve to champion a cause that aspired to unify all corners of the Francophone realm, nurturing a cohesive bond between the colonialists and the metropoles, under the virtuous and indomitable banner of La France. With this fresh in his mind, he spoke to a crowd as far as the eye could see in Toulon after his arrival on October 15th.

"My esteemed countrymen and compatriots of the greater Francophone realm,

Today, as I stand upon this embattled soil, I am reminded not just of the passion of 1789 and 1792 but the scars of betrayal and the sting of our losses. Our forefathers fought and bled, challenging both tyrants at home and enemies abroad, expelling the poisonous influences that dared threaten our sacred land. The revolutions that lit the fires of liberty in 1889 and 1892 also kindled the embers of revenge against those who would betray us.

The indomitable French spirit, birthed from our hallowed revolutions, wasn’t content remaining within our borders. It surged forth on a noble mission, planting seeds of enlightened society across continents. From the Saharan sands of Africa to the dense forests of Indochina, the tricolour flag was more than cloth and dye – it was a battle cry, a testament to French valour, justice, and progress.

To my brethren in arms and heart across the globe, never forget this: Our ancestors did not brave oceans and deserts for mere plots of land. They sought to spread our birth right, to forge a Francophone empire united in purpose and resolve. Wherever the French tongue is spoken, wherever liberty and justice reign, wherever the elite and oppressors are cast down, there is the spirit of France, alive and fierce.

The machinations of the old regime, the Royalists, and their treacherous ilk sought to shatter our unity. They are the very leeches that have sucked our land dry and conspired with outsiders to keep France on her knees. There are no distinctions among us - no Royalists, no Communards, no Bonapartists - only true Frenchmen and those who betray her. We are bound by a shared destiny, unyielding against those who seek to divide and conquer us.

The world now witnesses the Royalist menace, who in their blind ambition, trample upon our legacy. In cahoots with the Germans and the perfidious British, who once stole from us our rightful dominion in Suez and now conspire to isolate us, they aim to throttle our grand civilization. But we will choke their ambitions with our resolve. Every Francophone, from metropolitan streets to distant colonies, must rise! Repel the Royalist oppressors, denounce their foreign allies, and roar your allegiance to the unified might of the Francophone world.

Here, in the beating heart of France, the trinity of workers, farmers, and soldiers stands ready, ever-vigilant against betrayal. Under my guidance, with the force of our reinvigorated Popular Army, we will strike down those who dare tarnish the French legacy. Our mission spans not only our homeland but every land where French culture and spirit thrive. Every village, every city echoing with our language and culture is hallowed ground.

France isn't mere borders and maps; she is a burning ideal, a living testament to unity, sacrifice, and revenge against her foes. From the iconic landmarks of Paris to the farthest colonial outposts, we rally under our sacred tricolour. We will raise an army, a force of vengeance and justice, to wrest control from traitors and foreign meddlers.

I dream of a France that is once again the jewel of the world, where industries prosper, and our lands flourish under our vigilant watch. Every Frenchman, at home or abroad, will bask in the glory of a nation reborn, fierce and uncompromising. In our shared vision runs a single, potent truth – we are one, indivisible and unyielding against all who threaten us.

To achieve this, we must unite, organise, and roster a Popular Army of the people of France and all those who yearn for its ideals beyond. This army will fight the Royalists and drive them to the sea. In the name of our storied past and a future yet to be written, I summon every Francophone to arms. Together, we'll defend our way of life, ensure our rightful place in the world, and vow that every inch of French land, every drop of its waters, shall be reclaimed and defended.

For the glory of France and the indomitable spirit of the Francophone realm - All to the French!"

The eloquent proclamation by Généralissime Boulanger sent ripples through the hearts and minds of the Fédérés and further afield, into the territories of the Francophone world. This potent rhetoric, laden with historical references and unifying sentiments, rekindled the revolutionary flames reminiscent of the bygone eras of 1789 and 1792.

The stirring oratory struck a chord with the Fédérés, evoking a palpable sense of nationalism intertwined with the unyielding ethos of Francophonie that transcended beyond mere geographical bounds. His audacious call for the restoration of a society led by the workers, farmers, and soldiers mirrored the core ideology of nationalistic syndicalism, resonating profoundly with the Fédérés who envisioned a realm free of royalist and aristocratic yoke.

Across the expansive colonies, the speech was received with a blend of hope, fervour, and discernment. The colonies, each with its unique socio-political landscape, interpreted Boulanger's address through lenses tinted with their distinct experiences under the French aegis. In French Africa, where the yoke of colonialism had been perceived with varying degrees of acceptance and resentment, Boulanger's words spurred discussions, debates, and in some quarters, ignited the spark for a shared Francophone identity irrespective of racial or territorial delineations.

In other areas, like French Indochina, the Monarchy’s client patronage network held firm and the Crown would retain sway. The notion of a united Francophone society found a foothold among many who yearned for an equitable representation and shared prosperity under the tricolour. For many, the speech called to those who felt they were progressing and advancing to become French - an upper class of sorts in native populations, known as the Évolué.

The neighbouring European realms with French-speaking populace, such as Belgium and Switzerland, found themselves in a difficult position. Boulanger’s rhetoric, while evoking a sense of shared cultural heritage, also incited debates on the extent of allegiance to the broader Francophone narrative - something that would increase in the near future. The dichotomy of preserving national sovereignty while aligning with the grander Francophone ethos presented a complex tableau of diplomatic and ideological deliberation. Angst across France’s neighbours grew as they knew, deep down, that Boulanger would reunite France.

Last edited:

Part 5, Chapter XLI

V, XLI: The Panic of 1892

The growing descent of France into Civil War, while not a surprise given the instability that plagued the country leading up to it, still shocked many worldwide. However, its effects, distant upon the eruption of hostilities, came closer to home in the following weeks. Financial markets had remained stable initially, but after the return of Boulanger to France and its expected effect on the outcome of the conflict, countries faced a world with a significantly handicapped France, the world’s fifth largest economy as the Winter of 1892 set in.Finance and Trade witnessed a financial cataclysm on November 18th, 1892, that would be etched in the annals of economic history as a stark reminder of the delicate interdependence of global trade and finance. At the heart of this maelstrom was the return of Boulanger to mainland France and the subsequent worsening of the French conflict into a civil war that tore through the tapestry of European commerce and sent shockwaves across the Atlantic, precipitating the so-called "Panic of 1892."

Part 1 - Dislocated Trade, Dislocated Opportunities

As France descended into chaos, with the strife between the Royalists and the Boulanger-led Actionists intensifying, trade routes that crisscrossed the continent began to wither. The Actionist capture of key ports like Marseille and Bordeaux led to acute shortages, sending staples soaring prices. The famed wine harvests of Bordeaux, a commodity once poured liberally at the tables of the affluent from London to St. Petersburg, became a scarce luxury, with prices doubling, then tripling by the end of October.The repercussions were not confined to France. The rebellion disrupted the colonial resource flow, especially from Algeria, where the insurrection against Governor-General Jules-Martin Cambon's administration culminated in his tragic demise and the expulsion of French authority. This cessation of resources from North Africa sent ripples through the economies of nations dependent on these raw materials, causing manufacturing slowdowns in Germany and textile shortages in Britain as the Autumn hit.

Dakar Port, 1892

Maritime trade routes underwent an involuntary renaissance as British and German navies, seeking to protect the French Royalists informally, patrolled the waters with a vigilant eye, compelling shipping to circumnavigate conflict zones. Chamberlain and the War Secretary, Senator Arthur Balfour, announced to the commons on October 3rd that the Navy would patrol shipping routes and protect ships from attack as they travelled the French coast and in the vicinity of French colonies. This serendipitously benefited the United States and the British dominions, which experienced an uptick in maritime traffic, offering a brief economic boon amidst the burgeoning crisis.

Careful international traders avoided major French-held colonial ports for fear of the supposed anarchy that awaited them. The Royalist Government’s Colonial Minister, Émile Chautemps, urged the other Great Powers to both lift the blockade on French shipping from these ports and encourage their governments to inform traders and merchants that French colonial ports remained both safe and open on October 6th, as ports like Dakar, one of the biggest refuelling stations in the world, were turned to ghost towns.

Part 2 - The Crédit Lyonnais Affair

The most pernicious effect of the French conflict was the pervasive climate of uncertainty that settled over European markets. Skittish at the prospect of their capital being ensnared in the continental tumult, investors began withdrawing from European ventures. The investor panic was spurred by Crédit Lyonnais, a major European financial institution, when it was forced to declare on November 15th that its assets had been seized by the rebel administration of the city, leading to a loss of around 10,000,000 francs. This collapsed the value of the Franc, destabilised currency markets, and led to massive inflation in the French mainland.The developments sent shockwaves through the international financial community beyond the immediate borders of France. This economic upheaval rippled outward, affecting the stock exchanges of London, Frankfurt, and New York as investors scrambled to assess the potential impact on their own economies and financial systems. European companies, already cautious in the face of France's internal strife, tightened their purse strings further, and a credit squeeze ensued, putting additional pressure on trade and industry. This economic contagion threatened to spiral into a broader financial crisis, with the possibility of a banking collapse that could engulf Europe and even across the Atlantic.

In response to the crisis at Crédit Lyonnais, foreign branches in Alexandria, Cairo, New York, Smyrna, and Brussels found themselves in precarious positions. Local financial authorities placed these branches under heightened scrutiny, ensuring that operations complied with local laws and safeguarded the interests of domestic investors.

A series of negotiations ensued, led by diplomats and international finance experts, to determine the fate of these branches and the accounts therein. The talks aimed to balance the need to protect investors and the complex legalities of international finance. The outcomes of these discussions varied by location, with some branches agreeing to enhanced oversight by local financial authorities. In contrast, others negotiated joint administration agreements, sharing oversight responsibilities between bank officials and international representatives.

Crédit Lyonnais Headquarters, Lyon

Breaking with recent foreign policy, Britain and Germany led negotiations with the Royalist Government to prevent a greater financial contagion. Restrictions on French assets in Egypt and other British colonies were relaxed; Chancellor Randolph Churchill and President-Regent Stanley spearheaded a negotiation with the Royalist Government to secure the Bank of France using loans from an international consortium of British, American, and German banks. While the deal was humiliating and debilitating for the French Government, it was necessary for survival. Britain and Germany, in particular, used the loans to increase influence over the Royalist Government.

The response to the plight of Crédit Lyonnais' foreign branches was marked by a concerted effort to avert a legal quagmire. Recapitalized, the Bank of France took a leading role in brokering arrangements, allowing for shared oversight and ensuring that the bank's operations could continue under a cooperative framework. These delicate negotiations resulted in a patchwork of agreements, reflecting the countries' diverse legal systems and economic interests. The resulting arrangements were complex and often provisional, but they staved off the immediate threat of a more extensive financial collapse.

In the wider melee, the Royalist Government closed the Paris Bourse for a week after November 18th, leading over the next year to a rush to delist and head to Britain and the United States for major European companies. Equally, Frankfurt positioned itself to take over a percentage of stock trading. As a financial and economic hub for Western Europe, Paris was taken by a terminal illness in November 1892 that would not recover for some time. Fears about France’s status post-war took a significant turn for the worse after

This investor trepidation hastened the Panic of 1892. European capital, which had flowed generously into American railroads and industries, retreated abruptly. The American economy, already reeling from speculative excesses and overinvestment, was ill-prepared for the European withdrawal. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, a titan of American industry, became an early casualty, declaring bankruptcy and igniting the panic that engulfed the nation's banking system. The Harrison administration, focusing on the transition to the incoming Cleveland administration, was blindsided by the development and would be blamed for the dithering that led to the Railroad’s collapse.

As commodity prices fluctuated wildly due to the conflict, global trade balances shifted. France's inability to export its luxury goods and agricultural produce created a vacuum quickly filled by competitors. A worldwide market for Spanish wine, British-produced silk, and Italian agricultural products grew. Nevertheless, the sudden shifts led to economic instability transcending borders, exacerbating the financial crisis.

The search for safe-haven assets saw a global rush for gold, exacerbating the strains on U.S. gold reserves. The United States, steadfast in its commitment to the gold standard, watched its reserves dwindle as investors sought the security of the precious metal, fearing currency devaluations amidst the growing crisis. The gold crisis emboldened the Free Silver movement, whose two wings, the moderate Anti-Administration Democrats and Republicans and the Farmer-Labor Party, allied with one another to call for immediate action. This crisis precipitated the decision by lawmakers to bring forward the Portrait Gallery straw poll of the contingent election to alleviate fears of an unstable transfer of power following the Presidential Election a few weeks earlier.

Part 3 - A House Divided

The shockwaves of Credit Lyonnais' collapse rippled across the Atlantic, igniting fierce debates within the United States' political arena. The Farmer-Labor Party seized upon the crisis, viewing it as vindication of their long-held stance on monetary reform. At rallies and in the halls of Congress, FLP leaders called for immediate implementation of free silver policies, arguing that a more inflationary stance would shield American workers from the international financial storm. They advocated for the nationalization of railways and telegraphs, pointing to the successful state-run models established by S. B. Erwin in Kentucky as a model for national policy. Some called on the electors to overturn their expected election of Grover Cleveland as President and instead elect a unity candidate committed to Free Silver.In the Republican camp, the Credit Lyonnais debacle exacerbated the existing schism between the Progressive and Conservative wings. Progressive Republicans, while not fully aligning with the FLP, called for robust regulatory frameworks to protect American industries. Conservative Republicans, led by outgoing President Harrison, held firm on the gold standard, advocating for austerity measures as a bulwark against the encroaching economic turmoil. The Conservatives urged lawmakers to stay the course and, through gritted teeth, confirm Cleveland’s appointment as President.

Within the Democratic Party, the Silver Democrats found new ammunition against the Gold Democrats' platform. They pushed for bimetallism with renewed vigour after the Panic of 1892, aligning with the FLP's criticism of the gold standard. Despite his victory in the contingent election, Grover Cleveland found his position on free trade and smaller government increasingly at odds with the shifting mood of his country as a whole.

The expected ascension of Grover Cleveland to the presidency in a contingent election marked a pivotal moment in American politics. Though seething at Gresham's defection, the Farmer-Labor Party looked forward to leveraging the crisis to further their populist agenda in the upcoming congressional session. Meanwhile, the debate over monetary policy intensified, with anti-French sentiment stoked by those who viewed the French Civil War as the catalyst for America's financial woes. Xenophobic rhetoric grew in intensity, particularly in regions with significant French immigrant populations, as politicians capitalized on nationalistic fervour to rally support for protectionist and isolationist policies. All over the country, there was a wave of anti-French rage directed at businesses and individuals linked to France.

As the United States grappled with the economic fallout, the Panic of 1892 and the French Civil War catalysed a profound realignment in American politics. The Farmer-Labor Party's growth in both houses of Congress heralded a new era of populist influence. At the same time, the internal divisions within the Republican and Democratic parties suggested a redefinition of their core philosophies. The United States, like many nations observing the tumult in France, turned introspective, questioning the tenets of its economic and political identity on an increasingly interconnected yet unstable global stage.

Part 4 - The French against the World

Another regrettable facet of the financial turmoil was a collective belief that Boulanger’s return was a plot of all French speakers, not just the Actionists in France, that led to a virulent anti-French sentiment sweeping through nations, particularly those with significant French minorities. In Switzerland, home to a peaceful French-speaking populace, tensions mounted as refugees from the conflict sought asylum, straining local resources and stoking fears of the conflict spilling over the border. Belgium, with its deep cultural and linguistic ties to France, saw a rise in xenophobia as French nationals were increasingly viewed with suspicion, accused of harbouring sympathies for the Actionist cause. Flemish northerners, ever weary of French influence on their daily lives, began to question the nature of the Belgian state itself.The influx of French capital in the preceding years now appeared a poisoned chalice as calls for financial purges and the repatriation of German wealth grew louder in Germany. German financiers, once keen on French investments, now faced public scorn, and the French communities in cities like Berlin and Frankfurt found themselves marginalized, their contributions to the local economies forgotten amidst the rising tide of nationalism.

The broader military and economic concerns led to more significant calls from the Prussian elite for Kaiser Wilhelm II to exert control over the Government and use the military-industrial elite to guide policy rather than the Reichstag. This tug-of-war between parliamentary politics and real economic and military power would become a defining feature of German politics in the years to come.

In Milan, Italian Nationalists even attempted to raid a French-majority neighbourhood and expel the populous, but found local Fasci supporting the French-speakers. Two days of rioting ensued as Fasci build barricades around the city.

Milanese Police attempt to break down Barricades during the 1892 anti-French riots in the City.

Each of these attacks on the French-speaking populace across Europe tightened the unity of the community across national borders. Calls from French populations outside France to rebel and join the French crusade against European hegemons grew. Wherever there were significant French-speaking populations within Europe, Actionism grew. Actionists seized upon the growth in anti-French sentiment within France, mainly in Belgium and France. In a letter to his paper, Maurras declared, “The global crisis has unveiled the true nature of world diplomacy - it is the French against the World.”

The Panic of 1892, thus, was not merely an economic event but a catalyst for a social and political upheaval that reshaped the contours of international relations. Nations turned inward, protective of their interests, and the vision of a collective European identity, already fragmented, crumbled further. The French conflict, through the intricate interplay of economics, politics, and society, had redrawn the map of France and the lines of global cooperation, trust, and unity.

Last edited:

Oh boy, this could be interesting.

Is this turmoil in France going to affect the Francophones in Canada at all?

Is this turmoil in France going to affect the Francophones in Canada at all?

There will be some effects, indeed. Canada is already a fragile entity as it is, and there will be significant external factors on the body politic which will impact its future viability.Oh boy, this could be interesting.

Is this turmoil in France going to affect the Francophones in Canada at all?

Can’t say anymore, it will give too much away!

Part 5, Chapter XLII

V, XLII: Paris Falls, The Actionist Triumph

The period between November 1892 and January 1893 was a crucible of intense military planning and societal transformation. The meticulous organization of the Popular Army by Boulanger and his associates was a monumental task aimed at integrating an overwhelmingly civilian force into a cohesive military entity. Much of this was left to a Boulanger ally and the former Chief of Staff of the French Military, Eugène Galland, who defected to aid Boulanger and became the General of the Popular Army’s pivotal and influential Southern Division. Among the key moves General Galland made was to promote Ferdinand Foch to Divisional General, giving the leadership vigour and energetic leadership.

The period between November 1892 and January 1893 was a crucible of intense military planning and societal transformation. The meticulous organization of the Popular Army by Boulanger and his associates was a monumental task aimed at integrating an overwhelmingly civilian force into a cohesive military entity. Much of this was left to a Boulanger ally and the former Chief of Staff of the French Military, Eugène Galland, who defected to aid Boulanger and became the General of the Popular Army’s pivotal and influential Southern Division. Among the key moves General Galland made was to promote Ferdinand Foch to Divisional General, giving the leadership vigour and energetic leadership.

Backed by a ransacked Navy from Toulon, the Fédérés began to arm Actionists in Algeria to overthrow the rule of Jules-Martin Cambon, the Governor-General. Earlier in his career, Boulanger had been expelled from Tunisia on the insistence of Cambon, so the Généralissme took great pleasure in his downfall. Boulanger promised the formation of some form of home rule for Algeria within the reunited France. Algerians rose in support of Boulanger on December 18th, 1892, murdered Cambon, and expelled the French Army from Algiers. At Home, tentative attacks by the emerging Popular Army and successful defences of strongholds meant that the ultimate aim of the Civil War - to liberate Paris and occupy Versailles - became paramount to the Popular Army High Command.

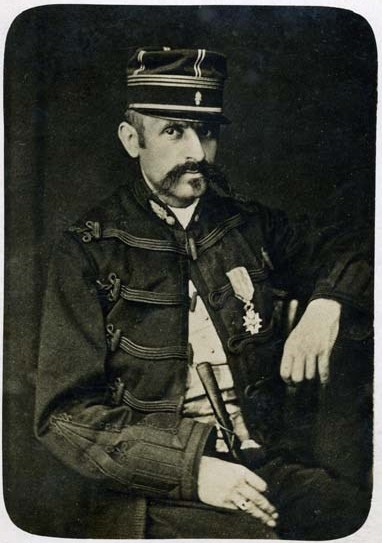

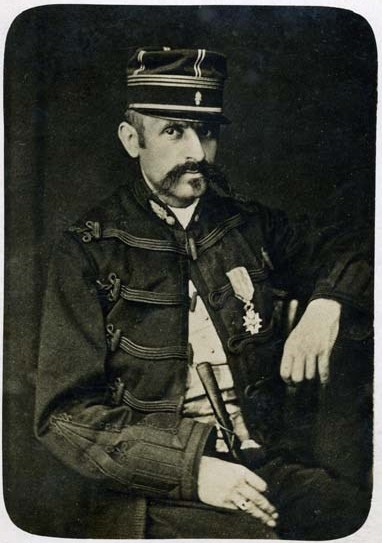

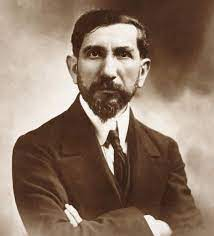

Jules-Martin Cambon, Governor of Algeria

January 1893 was a tipping point, wherein the consolidation of the Popular Army was at a stage that posed a substantial threat to the Royalist forces. The hinterlands of France were rapidly aligning with the Actionist cause, leaving the Royalists clinging to a precarious hold over Paris and parts of Central and East France. The Royalists began to lose control of the rear and home front, with disturbances pot marking France throughout January, stalled only by bitterly cold temperatures throughout the month, falling to -11.6c at the peak of the cold snap in Paris.

Once the weather improved in February, and seeing the situation as critical, Britain and Germany convened representatives in London to devise a method of protecting and containing the revolution exploding in France. The powers, including Britain, Germany, Iberia, and Italy, reached out to the Kingdom and offered increased weapons deliveries to the port of St Malo. The city had been targeted by guerrilla campaigns by pro-Boulanger forces. To ensure the deliveries were safe, the French Crown allowed the British Navy to dock and the Union Army to patrol the port.

In the East, Germany stepped up its troop numbers in Alsace and Lorraine, fearing an intervention by the Popular Army. It informally agreed with France to deploy its soldiers on the Franco-German border to protect German and French territory from Actionist attacks and to assist the Royal Army several miles inland. Five thousand troops were stationed on the Italian border in preparation for an invasion.

With foreign soldiers on French soil, the pro-Boulanger coalition, hastily organised up to now, looked to build key institutions to legitimise their rule and present themselves as an alternate government. The decision to call in foreign soldiers also ended any hopes of a peaceful compromise that could have restored a reformed status quo: after the decision to call the English in, the Kingdom and all of its supporters had to be destroyed. Foch, stressing the need for a “lightning army” to continue the rapid liberation of Royalist cities, announced a new general offensive on January 23rd.

The Popular Army’s Eastern Division pushed out from their western enclave, captured key towns like Saint-Louis, and overtook the Swiss border crossing on 31st January 1893. The Swiss Government announced that 15,000 troops would be deployed to the French border to ensure security and prevent a spillover. Adding the Swiss presence to the German, Iberian, Italian, and British presence around France’s border meant the country suddenly had the most fortified frontier on the planet.

Simultaneously, more and more Army units defected to the Popular Army. The group had better rations and pay and looked to be on the winning side. The drain of resources from the Royalist Army was palpable: the force lost around 1/3rd of its men between September and January 1893, according to Emile Zola’s The Breaking Point. Further humiliation for the Royalists occurred on February 2nd when forces from the Popular Army’s Northern and Eastern Divisions met at Troyes, creating the first land bridge between two rebel-held areas.

A victory for the combined Popular Army on February 7th in Nancy, overrunning the town as stranded Royalists defected, showed the Germans that intervening further into French territory would be fruitless, the Popular Army was an effective fighting force, and the primary objective for Germany should be to protect Alscace-Lorraine. Fearing a battle between the Imperial Army and Popular Army imminently, on February 8th, the order came to retreat from all lands not currently within the German Empire.

The February 16th capture of St Etienne after three days of fierce fighting confirmed the momentum of the Actionists, as they joined up the three divisions of the Popular Army and created a contiguous land mass under the Généralissme’s control, split the Royalist-held territory in two, and prevented the creation of successful supply lines, disrupting the government critically. The victory at St Etienne, which had passed between Royalist and Rebel control several times over the last few months, was symptomatic of the demoralised Royalist Army viewing the conflict as fruitless. Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was placed in charge of a new lightning force to ensure the expulsion of all foreign troops from French soil.

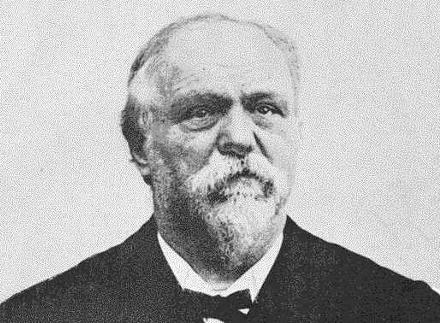

Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

After St Etienne, Boulanger declared a general amnesty to any non-commanding soldier in the Royalist Army. The command and supply structure was utterly broken, and the victories of Troyes and St. Etienne also disrupted rail transport for Royalist police and soldiers around France, as both were crucial interchanges. Essentially, after St Etienne, the situation was dire for the Kingdom of France. The British, German, and American Governments advised all citizens to leave Paris on the same day as the general amnesty, as each power realised that the Kingdom couldn’t survive. In an extraordinary step, the countries closed their embassies in Paris, and diplomats were hurried out of the rapidly emptying capital.

The capture of a section of the Paris-St Etienne Railway allowed the Popular Army to push up the line, securing cities along it. The capture of Vierzon placed the Actionists just over 200km from Paris, with one major city between them and the liberation of the capital: Orléans. General de Boisdeffre quickly assembled a group of what remained of his effective fighting force, around 5,000 Royalist soldiers, to defend the city and the road to Paris on February 21st.

De Boisdeffre spoke openly about the importance of the upcoming battle, describing it as “the defence of liberty in France from a militaristic band of rebels.” The Kingdom of France’s European allies accepted that the war was probably coming to an end. Despite a stubborn defence led by de Boisdeffre, Orléans fell on February 24th, and de Boisdeffre was killed in the battle, extinguishing the best General available to the Kingdom. General François Claude du Barail was appointed to replace de Boisdeffre, but his impact would be negligible.

In Paris, after the death of de Boisdeffre, morale among the Royalists plummeted. The refugees used the defended corridor from Paris to the North West and into the British-held port of Saint-Malo to escape to Britain. Of a heavily depleted population of just over 95,000 in the city on the day of the fall of Orléans, only 55,000 remained by the beginning of March. The road from Paris to Saint-Malo, a four-day journey, was referred to as “The Trail of Tears” by the Royalist community.

While the Actionists thought that the Royalists would defend the capital with a ferocity unseen in much of the conflict, the leaders of the rebellion, chiefly Généralissme Boulanger, decided the time had come to send the top leadership north to build morale. Boulanger used the opportunity presented to him.

On the 26th of February, Boulanger, in the smouldering streets of Orléans, declared that his army represented the General Will of the French People, Grand Chancellery was an illegal government, and, given the situation and the apparent investiture of the power of the French people in him, he had the right to appoint a temporary Provisional Government comprised of leading Fédérés to assume control. The Généralissme also declared the adoption of the French Republican Calendar (making the date 8 Ventôse, 101) as the state's official calendar.

As the proclamation was held on the day marked ‘Violette’ in the Republican Calendar, the government was colloquially called le Directoire Violette. Auguste Keufer, Fernand Pelloutier, Charles Maurras, Maurice Barrés, René Boylesve, and Frédéric Amouretti were appointed as members of the Government, along with General Galland and General Foch.

This was, significantly, the first time a rival government to the Grand Chancellery had been appointed: the Actionists didn’t believe that they would have the right to declare a government without Boulanger, so they insisted that while the King and Government were illegal, a provisional government wouldn’t have a mandate without Boulanger, and they would have to simply await the return of the Head of State to appoint a new government, and therefore spent most of the early parts of the war with completely decentralised leadership.

With a new government in place, the Actionists and Boulanger assumed power by assuming they were in control. Contact with embassies and colonies was established but not completely reciprocated - many refused to listen to the Fédérés. The rebels only really had a foothold in Algeria, parts of Tunisia, Senegal, French Guinea, Upper Volta, and French Sudan, where sympathetic (and power-hungry) colonialists had quickly seized upon the contents of Boulanger’s October speech and decided to turn local native populations against the colonial officials. Still, control was patchy in French Africa and nonexistent in French Indochina and the Pacific territories. In Senegal, only the ‘Four Communes,’ a group of the four oldest French settlements - Gorée, Dakar, Rufisque, and Saint-Louis - continued to recognise the King’s authority after the fall of Paris in Senegal.

To support and foster support for the rival government in Asia, Actionists sent future Foreign Affairs Director Louis de Geofroy to China to court favour with the Qing Government, which would soon bring benefits. Boulanger also sent plenipotentiaries to Moscow and Vienna to curry favour with France’s erstwhile allies. Lukewarm in their support for the restored Kingdom, seeing it as weak and a lackey of the Accord Powers, Russia recognised the new government. Not wishing to support the renewed abolition of the French monarchy but keen to protect its financial health and, hopefully, restore financial support, Austria followed a few days later.

Louis de Geofroy

Still, the small matter of recapturing the capital, plus a swath of territory in the North West and East, remained the new government's primary task. Now able to move freely around the country, General Galland rostered a force of around 22,000 from surrounding regiments, completing the troop movements on March 5th. From there, they marched to the Palace of Fontainebleau, southwest of Paris, where they overran a Royalist patrol, killing 150 and opening the road to the capital. The next day, the Popular Army marched to Melun, liberating the town with next to no fighting: those who escaped Fontainebleau warned the Melun Garrison that the Actionists were approaching, so their commander, Henri de Gaulle, negotiated a surrender of his men, most of whom subsequently defected to the Actionist side to join the assault on Paris.

In Versailles, the seat of the French Royalist Government, senior military figures urged King Louis-Phillippe to evacuate. General du Barail declared that “every man and boy must be used in the defence of the capital from the rebels,” but few took his call seriously. The King insisted he must be alongside the soldiers defending Paris, but summing up the chaos engulfing the centre of the Kingdom, his escort and the military company attached to him never arrived. The Popular Army, by 9 p.m., had reached the edge of the city and La Santé Prison, where many surviving Actionists had been interned. They freed all the prisoners, and many joined the growing caravan of men rushing towards the city centre.

General Foch, commanding the first battalion that arrived at the Triangle de Choisy, entered buildings and dispersed literature that said the Popular Army would not take Paris by force, reiterated the call for amnesty to all non-commanding officers in the Royalist Army. Finally, the Grand Chancellery travelled to Versailles at 10 p.m. to evacuate the King to Rouen in Normandy. While he protested fiercely, he was ultimately convinced to pack up and go, not without a significant portion of the estate’s remaining valuables and the King’s personal treasures. The Palace at Versailles was abandoned by roughly 1 a.m. on March 7th.

There was a sense of foreboding everywhere in Paris on March 7th. Few slept, and most awaited some kind of action patiently. After news of the King's flight spread during the night, the sympathetic working-class neighbourhoods gathered to support Boulanger around 4 a.m., as the remaining, beleaguered Royalists battled 20km away against the rapidly advancing Popular Army. It would take until around 7 a.m. for the last Royalist units to be captured. Boulanger was whisked to the Hôtel de Ville at 9 a.m., in front of thousands of soldiers and residents of Paris, and declared the monarchy had been overthrown and the Provisional Government had assumed power. All police, army units, and other government workers were to report for duty as usual, but first, they would need to swear allegiance to Boulanger.

The Généralissme reiterated the desires expressed in his Toulon Address and the call for “learned Frenchman, those wronged by the previous regime, and those who felt afraid: return to a country opening its arms.” The next day, the rostered French Army units gathered in the centre of Paris and declared their allegiance to Boulanger. While the Kingdom would struggle for a few weeks, the glorious return of Boulanger to Paris is the defining image of the Second French Revolution. Royalism was practically defeated there and then.

After the fall of Paris, refugees fled in two directions. Some went to Normandy and Britanny, where the remaining French Army had set up its defensive lines, and the King had declared the seat of power. However, Royalist officers fighting in the north of the country were said to be fleeing with their men across the thin border between the Kingdom of France and the Kingdom of Belgium. Poperinge on the border saw nearly 28,000 refugees, fleeing police - targetted viciously by the National Guard and Fédérés - and deserting soldiers squeezed through a strip of about 60 km controlled by the Royalists from Dunkirk to Tourcoing.

Most travelled by trains, constantly running out of Paris between March 5th and 8th. Others walked or hitched rides or rode carriages. Still, all attempting to escape Actionist France finally encountered a thin, hotly contested 15km wide strip of road and land, complete with the constant gunfire of the Popular Army's Northern Division, the only safety route. Still, many of the refugees successfully spilled out over the border in the days leading to and after the fall of Paris, as the Socialists, Anarchists, and Republicans had in 1889. The humanitarian and diplomatic crisis caused by the actions of just a few days would continue to reverberate as the events completely changed our world's travel direction. Against the odds, the Actionists looked set for victory.

The period between November 1892 and January 1893 was a crucible of intense military planning and societal transformation. The meticulous organization of the Popular Army by Boulanger and his associates was a monumental task aimed at integrating an overwhelmingly civilian force into a cohesive military entity. Much of this was left to a Boulanger ally and the former Chief of Staff of the French Military, Eugène Galland, who defected to aid Boulanger and became the General of the Popular Army’s pivotal and influential Southern Division. Among the key moves General Galland made was to promote Ferdinand Foch to Divisional General, giving the leadership vigour and energetic leadership.

The period between November 1892 and January 1893 was a crucible of intense military planning and societal transformation. The meticulous organization of the Popular Army by Boulanger and his associates was a monumental task aimed at integrating an overwhelmingly civilian force into a cohesive military entity. Much of this was left to a Boulanger ally and the former Chief of Staff of the French Military, Eugène Galland, who defected to aid Boulanger and became the General of the Popular Army’s pivotal and influential Southern Division. Among the key moves General Galland made was to promote Ferdinand Foch to Divisional General, giving the leadership vigour and energetic leadership.

Backed by a ransacked Navy from Toulon, the Fédérés began to arm Actionists in Algeria to overthrow the rule of Jules-Martin Cambon, the Governor-General. Earlier in his career, Boulanger had been expelled from Tunisia on the insistence of Cambon, so the Généralissme took great pleasure in his downfall. Boulanger promised the formation of some form of home rule for Algeria within the reunited France. Algerians rose in support of Boulanger on December 18th, 1892, murdered Cambon, and expelled the French Army from Algiers. At Home, tentative attacks by the emerging Popular Army and successful defences of strongholds meant that the ultimate aim of the Civil War - to liberate Paris and occupy Versailles - became paramount to the Popular Army High Command.

Jules-Martin Cambon, Governor of Algeria

January 1893 was a tipping point, wherein the consolidation of the Popular Army was at a stage that posed a substantial threat to the Royalist forces. The hinterlands of France were rapidly aligning with the Actionist cause, leaving the Royalists clinging to a precarious hold over Paris and parts of Central and East France. The Royalists began to lose control of the rear and home front, with disturbances pot marking France throughout January, stalled only by bitterly cold temperatures throughout the month, falling to -11.6c at the peak of the cold snap in Paris.

Once the weather improved in February, and seeing the situation as critical, Britain and Germany convened representatives in London to devise a method of protecting and containing the revolution exploding in France. The powers, including Britain, Germany, Iberia, and Italy, reached out to the Kingdom and offered increased weapons deliveries to the port of St Malo. The city had been targeted by guerrilla campaigns by pro-Boulanger forces. To ensure the deliveries were safe, the French Crown allowed the British Navy to dock and the Union Army to patrol the port.

In the East, Germany stepped up its troop numbers in Alsace and Lorraine, fearing an intervention by the Popular Army. It informally agreed with France to deploy its soldiers on the Franco-German border to protect German and French territory from Actionist attacks and to assist the Royal Army several miles inland. Five thousand troops were stationed on the Italian border in preparation for an invasion.

With foreign soldiers on French soil, the pro-Boulanger coalition, hastily organised up to now, looked to build key institutions to legitimise their rule and present themselves as an alternate government. The decision to call in foreign soldiers also ended any hopes of a peaceful compromise that could have restored a reformed status quo: after the decision to call the English in, the Kingdom and all of its supporters had to be destroyed. Foch, stressing the need for a “lightning army” to continue the rapid liberation of Royalist cities, announced a new general offensive on January 23rd.

The Popular Army’s Eastern Division pushed out from their western enclave, captured key towns like Saint-Louis, and overtook the Swiss border crossing on 31st January 1893. The Swiss Government announced that 15,000 troops would be deployed to the French border to ensure security and prevent a spillover. Adding the Swiss presence to the German, Iberian, Italian, and British presence around France’s border meant the country suddenly had the most fortified frontier on the planet.

Simultaneously, more and more Army units defected to the Popular Army. The group had better rations and pay and looked to be on the winning side. The drain of resources from the Royalist Army was palpable: the force lost around 1/3rd of its men between September and January 1893, according to Emile Zola’s The Breaking Point. Further humiliation for the Royalists occurred on February 2nd when forces from the Popular Army’s Northern and Eastern Divisions met at Troyes, creating the first land bridge between two rebel-held areas.

A victory for the combined Popular Army on February 7th in Nancy, overrunning the town as stranded Royalists defected, showed the Germans that intervening further into French territory would be fruitless, the Popular Army was an effective fighting force, and the primary objective for Germany should be to protect Alscace-Lorraine. Fearing a battle between the Imperial Army and Popular Army imminently, on February 8th, the order came to retreat from all lands not currently within the German Empire.

The February 16th capture of St Etienne after three days of fierce fighting confirmed the momentum of the Actionists, as they joined up the three divisions of the Popular Army and created a contiguous land mass under the Généralissme’s control, split the Royalist-held territory in two, and prevented the creation of successful supply lines, disrupting the government critically. The victory at St Etienne, which had passed between Royalist and Rebel control several times over the last few months, was symptomatic of the demoralised Royalist Army viewing the conflict as fruitless. Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was placed in charge of a new lightning force to ensure the expulsion of all foreign troops from French soil.

Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

After St Etienne, Boulanger declared a general amnesty to any non-commanding soldier in the Royalist Army. The command and supply structure was utterly broken, and the victories of Troyes and St. Etienne also disrupted rail transport for Royalist police and soldiers around France, as both were crucial interchanges. Essentially, after St Etienne, the situation was dire for the Kingdom of France. The British, German, and American Governments advised all citizens to leave Paris on the same day as the general amnesty, as each power realised that the Kingdom couldn’t survive. In an extraordinary step, the countries closed their embassies in Paris, and diplomats were hurried out of the rapidly emptying capital.

The capture of a section of the Paris-St Etienne Railway allowed the Popular Army to push up the line, securing cities along it. The capture of Vierzon placed the Actionists just over 200km from Paris, with one major city between them and the liberation of the capital: Orléans. General de Boisdeffre quickly assembled a group of what remained of his effective fighting force, around 5,000 Royalist soldiers, to defend the city and the road to Paris on February 21st.

De Boisdeffre spoke openly about the importance of the upcoming battle, describing it as “the defence of liberty in France from a militaristic band of rebels.” The Kingdom of France’s European allies accepted that the war was probably coming to an end. Despite a stubborn defence led by de Boisdeffre, Orléans fell on February 24th, and de Boisdeffre was killed in the battle, extinguishing the best General available to the Kingdom. General François Claude du Barail was appointed to replace de Boisdeffre, but his impact would be negligible.

In Paris, after the death of de Boisdeffre, morale among the Royalists plummeted. The refugees used the defended corridor from Paris to the North West and into the British-held port of Saint-Malo to escape to Britain. Of a heavily depleted population of just over 95,000 in the city on the day of the fall of Orléans, only 55,000 remained by the beginning of March. The road from Paris to Saint-Malo, a four-day journey, was referred to as “The Trail of Tears” by the Royalist community.

While the Actionists thought that the Royalists would defend the capital with a ferocity unseen in much of the conflict, the leaders of the rebellion, chiefly Généralissme Boulanger, decided the time had come to send the top leadership north to build morale. Boulanger used the opportunity presented to him.

On the 26th of February, Boulanger, in the smouldering streets of Orléans, declared that his army represented the General Will of the French People, Grand Chancellery was an illegal government, and, given the situation and the apparent investiture of the power of the French people in him, he had the right to appoint a temporary Provisional Government comprised of leading Fédérés to assume control. The Généralissme also declared the adoption of the French Republican Calendar (making the date 8 Ventôse, 101) as the state's official calendar.

As the proclamation was held on the day marked ‘Violette’ in the Republican Calendar, the government was colloquially called le Directoire Violette. Auguste Keufer, Fernand Pelloutier, Charles Maurras, Maurice Barrés, René Boylesve, and Frédéric Amouretti were appointed as members of the Government, along with General Galland and General Foch.

This was, significantly, the first time a rival government to the Grand Chancellery had been appointed: the Actionists didn’t believe that they would have the right to declare a government without Boulanger, so they insisted that while the King and Government were illegal, a provisional government wouldn’t have a mandate without Boulanger, and they would have to simply await the return of the Head of State to appoint a new government, and therefore spent most of the early parts of the war with completely decentralised leadership.

With a new government in place, the Actionists and Boulanger assumed power by assuming they were in control. Contact with embassies and colonies was established but not completely reciprocated - many refused to listen to the Fédérés. The rebels only really had a foothold in Algeria, parts of Tunisia, Senegal, French Guinea, Upper Volta, and French Sudan, where sympathetic (and power-hungry) colonialists had quickly seized upon the contents of Boulanger’s October speech and decided to turn local native populations against the colonial officials. Still, control was patchy in French Africa and nonexistent in French Indochina and the Pacific territories. In Senegal, only the ‘Four Communes,’ a group of the four oldest French settlements - Gorée, Dakar, Rufisque, and Saint-Louis - continued to recognise the King’s authority after the fall of Paris in Senegal.

To support and foster support for the rival government in Asia, Actionists sent future Foreign Affairs Director Louis de Geofroy to China to court favour with the Qing Government, which would soon bring benefits. Boulanger also sent plenipotentiaries to Moscow and Vienna to curry favour with France’s erstwhile allies. Lukewarm in their support for the restored Kingdom, seeing it as weak and a lackey of the Accord Powers, Russia recognised the new government. Not wishing to support the renewed abolition of the French monarchy but keen to protect its financial health and, hopefully, restore financial support, Austria followed a few days later.

Louis de Geofroy

Still, the small matter of recapturing the capital, plus a swath of territory in the North West and East, remained the new government's primary task. Now able to move freely around the country, General Galland rostered a force of around 22,000 from surrounding regiments, completing the troop movements on March 5th. From there, they marched to the Palace of Fontainebleau, southwest of Paris, where they overran a Royalist patrol, killing 150 and opening the road to the capital. The next day, the Popular Army marched to Melun, liberating the town with next to no fighting: those who escaped Fontainebleau warned the Melun Garrison that the Actionists were approaching, so their commander, Henri de Gaulle, negotiated a surrender of his men, most of whom subsequently defected to the Actionist side to join the assault on Paris.

In Versailles, the seat of the French Royalist Government, senior military figures urged King Louis-Phillippe to evacuate. General du Barail declared that “every man and boy must be used in the defence of the capital from the rebels,” but few took his call seriously. The King insisted he must be alongside the soldiers defending Paris, but summing up the chaos engulfing the centre of the Kingdom, his escort and the military company attached to him never arrived. The Popular Army, by 9 p.m., had reached the edge of the city and La Santé Prison, where many surviving Actionists had been interned. They freed all the prisoners, and many joined the growing caravan of men rushing towards the city centre.

General Foch, commanding the first battalion that arrived at the Triangle de Choisy, entered buildings and dispersed literature that said the Popular Army would not take Paris by force, reiterated the call for amnesty to all non-commanding officers in the Royalist Army. Finally, the Grand Chancellery travelled to Versailles at 10 p.m. to evacuate the King to Rouen in Normandy. While he protested fiercely, he was ultimately convinced to pack up and go, not without a significant portion of the estate’s remaining valuables and the King’s personal treasures. The Palace at Versailles was abandoned by roughly 1 a.m. on March 7th.

There was a sense of foreboding everywhere in Paris on March 7th. Few slept, and most awaited some kind of action patiently. After news of the King's flight spread during the night, the sympathetic working-class neighbourhoods gathered to support Boulanger around 4 a.m., as the remaining, beleaguered Royalists battled 20km away against the rapidly advancing Popular Army. It would take until around 7 a.m. for the last Royalist units to be captured. Boulanger was whisked to the Hôtel de Ville at 9 a.m., in front of thousands of soldiers and residents of Paris, and declared the monarchy had been overthrown and the Provisional Government had assumed power. All police, army units, and other government workers were to report for duty as usual, but first, they would need to swear allegiance to Boulanger.

The Généralissme reiterated the desires expressed in his Toulon Address and the call for “learned Frenchman, those wronged by the previous regime, and those who felt afraid: return to a country opening its arms.” The next day, the rostered French Army units gathered in the centre of Paris and declared their allegiance to Boulanger. While the Kingdom would struggle for a few weeks, the glorious return of Boulanger to Paris is the defining image of the Second French Revolution. Royalism was practically defeated there and then.

After the fall of Paris, refugees fled in two directions. Some went to Normandy and Britanny, where the remaining French Army had set up its defensive lines, and the King had declared the seat of power. However, Royalist officers fighting in the north of the country were said to be fleeing with their men across the thin border between the Kingdom of France and the Kingdom of Belgium. Poperinge on the border saw nearly 28,000 refugees, fleeing police - targetted viciously by the National Guard and Fédérés - and deserting soldiers squeezed through a strip of about 60 km controlled by the Royalists from Dunkirk to Tourcoing.

Most travelled by trains, constantly running out of Paris between March 5th and 8th. Others walked or hitched rides or rode carriages. Still, all attempting to escape Actionist France finally encountered a thin, hotly contested 15km wide strip of road and land, complete with the constant gunfire of the Popular Army's Northern Division, the only safety route. Still, many of the refugees successfully spilled out over the border in the days leading to and after the fall of Paris, as the Socialists, Anarchists, and Republicans had in 1889. The humanitarian and diplomatic crisis caused by the actions of just a few days would continue to reverberate as the events completely changed our world's travel direction. Against the odds, the Actionists looked set for victory.

Supplemental: 1893 US Presidential Inauguration

Excerpt from "Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890's" by R. Hal Williams

Chapter 9: A House Divided - The Contingent Election of 1892 and Cleveland's Ascension“The contingent election of 1892, held in January 1893, marked a watershed moment in the annals of American politics. In the wake of the Credit Lyonnais collapse and the ongoing French Civil War, the United States found itself at a crossroads, both economically and politically. The election of Grover Cleveland, while expected, did not pass without intense debate and the crystallization of a profound partisan split.

As Cleveland prepared for his inauguration on March 4, 1893, the political landscape of America was undergoing a seismic shift. The Farmer-Labor Party, galvanized by the financial crisis, found their populist agenda gaining traction. Meanwhile, deep fissures were emerging within both the Republican and Democratic parties.

The term "Federalist" re-emerged in this tumultuous era, finding a new resonance. The moniker was first resurrected by a keen political journalist, Eleanor Randolph, who wrote for the Washington Post. In a column dated January 15, 1893, Randolph described the pro-Cleveland faction as "modern Federalists," evoking the early American political party that had advocated for a strong national government. This new Federalist group, rallying around Cleveland, was driven by a desire for national unity and a firm stance on isolation from the escalating European conflicts.

In stark contrast, opposition to Cleveland's presidency coalesced into what became known as the "Democratic-Republican" faction. The term, harking back to the early political rivalry between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans of Jefferson's era, was first used by Theodore S. White in a New York Times editorial. White argued that the opposition represented a blend of ideals from both major parties, unified in their resistance to Cleveland's policies and his approach to the national crisis.

This Democratic-Republican faction was a diverse coalition consisting of members from both traditional parties who opposed Cleveland's stance on monetary reform and isolationism. They criticized his commitment to the gold standard and his reluctance to engage more assertively in international affairs, particularly in light of the upheaval in France and its economic repercussions.

A sense of subdued urgency marked the inauguration of Grover Cleveland on March 4. In his address, Cleveland spoke of unity and resilience in the face of national challenges. However, the growing divide in the political fabric of the nation was palpable. The Federalists, although not yet an official moniker, championed policies aimed at steering the nation through the economic crisis with a focus on internal stability and a cautious approach to foreign entanglements.

As Cleveland took the reins of a divided nation, the Democratic-Republicans began to coalesce into a more formalized opposition. They advocated for more radical economic reforms and a reevaluation of America's role on the global stage. This opposition was not just a rejection of Cleveland's policies but a broader critique of the status quo, signalling a deepening discontent with traditional political alignments. They maintained an equidistance between the Federalists and the Farmer-Labor Party, believing a new course between the two would be needed to solve the country’s mounting issues.

The year 1893 thus began with the United States embarking on a path fraught with internal divisions and an uncertain future. The dual emergence of the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans marked a new era in American politics, one where old allegiances were questioned, and new coalitions were formed in response to unprecedented economic and global challenges. The stage was set for a decade that would redefine the American political landscape.”

Part 5, Chapter XLIII

V, XLIII: Founding a New Society

Surprisingly, little thought had been given to the ruling of France post-victory; it became clear over the first few days of the ‘liberation’ of Paris in March 1893. Rival divisions, factions, and agencies of the rebel movement all competed to occupy just about every building in Paris over the first few weeks. Having emptied considerably, an almost entirely new city emerged of activists, militias, volunteers, and a wide range of largely self-appointed officials.

Despite the jubilance, a sobering thought descended on those who now ruled France following the collapse of Royal authority in the capital. The ravages of the French Civil War left an indelible mark on the nation. Historians estimate that the conflict claimed the lives of approximately 490,000 souls, a staggering loss that resonated in every corner of French society. Economically, the toll was equally devastating.

The Destruction, by François Sallé (1893)

The destruction of infrastructure, the interruption of agricultural and industrial production, and the loss of valuable human labour cost the nation dearly, with estimates suggesting a staggering $10 billion in damages. The cities, once bustling centres of commerce and culture, lay in ruins, their streets silent save for the echoes of recent battles. The countryside, too, bore the scars of war, with fields left fallow and farms destroyed. As France stood at the crossroads of a new era, the monumental task of rebuilding these physical and societal structures loomed large, presenting a challenge that would shape the course of the nation's future.

The leading power brokers were the armed units: the National Guard - divided into local divisions and the federal force - and Popular Army units - which were split by differing political factions and regional commands. Significant tension existed between Popular Army units, especially senior and specialised units, and National Guard units in cities. Fights were breaking out all over the city between rival groups of Guardsmen and Soldiers, with the former complaining of the brutality of the latter, especially around prisoners.

Beyond the military power, trade unionists and labour officials through the CGT were incredibly important as they kept the factories running. The CGT had armed militias to protect factories and defend exports. These militias headed to Paris in droves, representing the radical left of Actionism. Alongside these were municipal leaders and volunteers, who kept the cities and towns running as Defence Committees and Communal Councils. In the wake of the liberation of the centre of Paris, a new Paris Commune was predictably declared. Still, its composition was significantly more diverse and less political, taking on more mundane tasks of municipal governance in the immediate days after the victory.

Moreover, each city was unique in its organisation, but if a job was to be done, there was a committee rather than a single point of authority. Paris was no different. Having been ruled by Boulanger and then the Kingdom for three years, however, and suffering significant population flight, it was perhaps understandable there would be a bit of a transition. A tense atmosphere pieced the first week, as suspicion of a Royalist counter-attack grew, but as the anxiety melted away, a question grew on everyone’s mind - What now?

It would take a week before delegates from across the country, bar those still occupied by the Royalists, arrived to discuss what to do in Paris. Much work had been done in the provinces to repair railway lines and get the logistical issues out of the way, but the delays were caused by arguments over who could go and what credentials they would need. In the end, everyone was allowed to show up as long as they were loyal to Boulanger and disavowed the King. This was pretty easy for many people in France, as the King’s imposition had turned Frenchmen against Frenchmen and caused a civil war. Boulanger returned and ended it.

Nearly 5,000 people, claiming to be ‘delegates,’ arrived. There were so many that there was no hall big enough to contain them all, so plenary sessions were done outside a city centre park in the cold before the delegates were split up into smaller groups to send representatives to a standing committee. The Directory led the convention, recognising the need to pull the unruly bunch in some direction. Still, even within the Directory, differing power bases and factions developed between the eight men who occupied the provisional government.

Fernand Pelloutier, Directory Member and One of the Leaders of the CGT

Keufer and Pelloutier represented the CGT and held sway within the vast militia apparatus, the Labour Committees, and the National Guard. While Maurice Barrés and René Boylesve were novelists, they and Amouretti represented the faction most associated with Boulanger. Still, they were less politically minded and more vaguely nationalistic than the left of the Directory. They held power through their relationship with Boulanger himself and, therefore, held considerable power within this provisional administration - and feared their influence might be diminished after drafting a constitution. Generals Galland and Foch were in a similar position, fearing that a transition to a civilian government would reduce the emerging power of the Popular Army.

Finally, there was Maurras. Maurras had a popular base, was thought of as one of the critical philosophers of the revolution, and was a crucial element in starting the schism. He was also entirely alone in the provisional government and, in private, believed that he would form the ‘true opposition’ within the Government itself. “My role is to expose the inadequacies of men like Keufer and his secret commitment to Internationalism,” Maurras told Sorel in a letter hours after his appointment to the Directory.

Sorel was the other figure, lurking from outside the Directory. Boulanger and Sorel, despite the former’s conversion to his beliefs, did not mix well on a personal level, so even when Maurras insisted he be included, Sorel politely declined. “I am better served observing rather than governing,” said Sorel to Boulanger when the latter invited him to join his provisional government. Very few in France would be capable of turning down the Généralissme - but Sorel might have been the exception.

Ironically, despite eschewing Internationalism as practised by Iberia, in the early days of post-Civil War France, Sorel was moving decisively away from Maurras’ growing militant nationalism and towards Keufer’s scientific and technocratic syndicalism. In a letter to Action Française, Sorel hinted at this subtle change.

“As I see it, the only way to rule France is to observe and examine the situation as it exists in reality,” Sorel said, “five major sources of power emanate and must be considered when deciding on the future direction of the governance of the Francophonie. The first is the National Guard, which protects the civilian population. The second is the Popular Army, whose sacrifice alongside the Guardsmen and Militias from the CGT allowed us to defeat the usurpers. The third is the CGT, without whose support our economic output would cease, and fourth, the supporters and organisers in communes and municipalities.”

“Finally, and most importantly, there is the overriding source of legitimacy for the state: Généralissme and undisputed leader of the French worldwide, Georges Boulanger. Any settlement on the governance of France and its territories beyond must incorporate these five power sources, or we are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the last regime,” he concluded.

George Sorel, architect of the 1893 French Constitution

Sorel was accurate in this assessment. Without the buy-in of all the stakeholders in the conflict, there would be no stable government in France and beyond. In a letter to Maurras, he rebuffed the young firebrands' attempts to exclude Keufer and potentially the CGT from the process. “It would be unwise to seek to alienate the labour force, given the workers and syndicates provided the initial spark for the Second Revolution,” Sorel noted.

Concerned about the potential to completely unravel the unity between the victor’s factions, Sorel took action and, after the plenary session, offered his services to the groups attempting to draft a constitution that would please all groups.

This recognition of the need for inclusive governance set the tone for the constitutional convention. Over several weeks, representatives from the various factions and power centres engaged in intense negotiations to draft a constitution for the newly liberated France. Sorel approached Keufer to ensure the discussions were characterised by a spirit of pragmatism, recognising the need to balance the diverse interests and ideologies that had come together in the struggle against the monarchy. “If we cannot achieve a synthesis of each of the goals of the revolutionaries, we are doomed to lose all the gains of the revolution and allow the Monarchy to regroup and return stronger,” Sorel said to the CGT leader.

As they stepped away from the bustling assembly, Sorel was reported to have mused, “Auguste, do you think we can truly unite these divergent paths?” Keufer, looking over the sea of delegates, responded, “It's like weaving a tapestry from different threads, Georges. Difficult, but not impossible if we remember the picture we're trying to create.”

Keufer listened and participated with a conciliatory spirit. He and Pelloutier, representing the CGT, advocated for a constitution that would institutionalise the role of workers in the governance process. They proposed the establishment of a state where groups representing different sectors of the economy, managed by the CGT, would play a key role. This approach aimed to ensure workers' voices were central in decision-making, particularly in economic matters.

Maurras was less engaged in the process, however, preferring to rally the people on the ground to continue his role as the firebrand rabble-rouser of the working class. At the same time as the convention was ongoing, he embarked on a public tour with Boulanger to encourage provincial citizens to continue the fight to eradicate the monarchy in Metropolitan France.

Charles Maurras, the youngest member of the French Provisional Government

Profiting from the disorganisation of the pro-regime elements at the local level, wherever he went, he encouraged the formation of a central ‘Vigilance Committee’ to, in his words, “assist the National Guard and Popular Army against the fifth column of metis and foreigners working against the society we, as Francophones, are building together. France is the culture, the guiding force in liberty. We must resist an attempt to roll back the gains we have made. Organise, centralise, and coordinate your efforts,” he said. Comités took this to mean a brutal strike against those deemed unsatisfactorily revolutionary.

These Vigilance Committees led to a new force of ultra-motivated Actionists searching for the enemy within. In weeks after, this energy transformed these groups into a further faction within the revolution, known as Comités. Comités would form the vanguard of Maurras’ followers and brutally suppress dissent, focusing on elements within the trade unions and civil society that came from the liberal parts of the Actionists.

In the days after the victory of the Actionists, especially in areas where Maurras and Boulanger visited, violence sky-rocketed as motivated “winners” of the revolution targetted the usual victims of repression on the Actionist side throughout the conflict: remaining foreigners in France, Jews, so-called ‘profiteers’ of the old system (mostly Bakers and those who had refused to collaborate with the new labour committees), protestants, and known monarchists.

Maurras' journey from a revolutionary philosopher to the head of the Comités was profound during these initial days. Initially seen as a thinker and a voice of the revolution, Maurras' rhetoric began to take a more pragmatic and authoritarian turn. As the leader of the Comités, he was no longer just advocating for ideas but was actively shaping the new order with his own hands. His speeches, once filled with philosophical musings, became directives and orders.

The Comités, under his command, swiftly evolved from a revolutionary tool to an instrument of order and control. This change was not without its critics; many within the revolution began to view Maurras with a mix of awe and apprehension. Some saw his newfound pragmatism as a necessary evil, while others whispered concerns of a potential return to authoritarianism, this time under a different guise. He had a physical transformation, too.