V, XXXI: The New Risorgimento

The year was 1892, and the winds of change that had swept across Europe found their way to Italy. The nation's history, like a mosaic of contrasting hues, was about to be painted with the vivid strokes of a new ideology – Actionism. As whispers of revolution and fervent cries for change echoed through the streets of France, the neighboring nation of Italy stood at a crossroads. The land of ancient civilizations and Renaissance art had been grappling with its own set of challenges in the late 19th century. Economic hardships, social disparities, and political upheavals had cast a shadow over the Italian Peninsula.

In the bustling squares of Italy, where oranges hung heavy on the trees, a movement was born. The Fasci Italiano, or Fasci d'Azione Italiano emerged as a beacon of hope for the disenfranchised. Inspired by the revolutionary winds that had swept across France, the Fasci galvanized the poorest and most exploited members of society. They transformed the frustrations and discontent of the masses into a coherent vision of a better future grounded in the establishment of new rights.

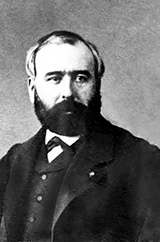

Giovanni Giolitti, Prime Minister of Italy

The movement's demands were straightforward – fair land rents, higher wages, lower local taxes, and the equitable distribution of common land. But within these seemingly simple demands lay the aspirations of a marginalized population yearning for justice. From July to October 1892, approximately 170 Fasci were established in Italy. As the movement gained momentum, its membership swelled to over 300,000 by the time November's election loomed on the horizon. Public demonstrations became a constant source of concern for the Italian Government.

The Fasci was a federation of various associations encompassing farm workers, tenant farmers, small sharecroppers, artisans, intellectuals, and industrial laborers. They came together under the banner of change, their unity symbolized by the bundle of sticks – "Fascio" – signifying that while a single stick may break, a bundle was unbreakable.

Amidst the tumultuous sea of political ideologies, the Italian Fasci carried a unique perspective on Actionism. Many of its leaders were devout Catholics, and this infusion of faith into their movement lent it a distinct character. In their meeting halls, crucifixes hung alongside purple Actionist flags, and portraits of revolutionaries like Garibaldi, Mazzini, Sorel, and Marx adorned the walls.

Their conviction led them to proclaim, "Jesus was a true socialist and wanted just what the Fasci were demanding."

As the November 1892 Election drew near, Italy found itself standing on the precipice of change. The conditions leading up to the election were far from ideal. The working class, a significant segment of the population, remained excluded from the electoral process. The contesting parties included the Liberals under Giovanni Giolitti, the Right led by Antonio Starabba di Rudinì, and the Radicals headed by Felice Cavallotti. Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, now at the helm of the Italian Government, faced the daunting task of guiding the nation through these turbulent waters.

Beyond Italy's borders, the nation's allies, Germany and Britain, watched with keen interest. As members of the Accord powers, they both had a vested interest in Italy's stability. The outcome of the election held the potential to not only reshape Italy's domestic landscape but also influence its diplomatic relationships. Within the political spectrum, another new movement was brewing. The Social Democratic Party of Italy, founded in 1892 as the Party of Italian Workers, aligned itself with the principles of Pactism. This movement stood in stark contrast to the Actionists, condemning their deviation from the ideals of Pactism. In the midst of Italy's political maelstrom, the PSI sought to carve out its own path.

Amidst the fervor of the Fasci's emergence, Italy hurtled toward a pivotal moment in its history. As the nation grappled with newfound hope and mounting tension, the stage was set for the November 1892 Election, an event that would both test and redefine the nation's political landscape. The nation was poised for transformation, and the choices made in the coming days would shape its destiny. The storm of Actionism had arrived, and Italy was about to be swept up in its tempestuous embrace.

The sun hung low in the sky, casting long shadows across the Italian Peninsula as the nation held its collective breath, awaiting the outcome of the pivotal November 1892 Election. This election was not just a contest between political parties; it was a referendum on the path Italy would tread. As the results of the election slowly unfolded, they painted a bleak and revealing picture of Italy's political landscape. The new composition of the Chamber of Deputies did little to alleviate the growing tensions within the nation.

The Liberal faction emerged as the victor, but their victory was hardly a resounding one. Securing 369 seats, they had garnered the largest share, yet it was evident that Italy was not embracing their vision with open arms. Their message of moderation and gradual reform had, at best, struck a cautious chord with the voters. The Right managed to secure 76 seats, a testament to their unyielding conservatism. Still, their ideals faced an uphill battle against a changing political climate, and their influence seemed to wane. The Radicals found themselves with 63 seats. Their vision for radical change, though passionate, had failed to ignite a widespread fervor among the electorate.

However, the election was marred by controversy and allegations of vote-rigging and manipulation. In fear of Actionist sympathisers gaining seats in the Chamber, Radicals were arrested prior to the election and found themselves harassed and oppressed by the police. Key Actionist and Socialist figures were targetted also, and the Government resorted to vote rigging to ensure they retained their majority, with the tacit approval of the King and the Accord Powers, who wished to prevent the Actionist revolution from spreading to the Italian Peninsular.

Accusations of irregularities echoed across Italy, casting a long and dark shadow over the electoral process. Both the Fasci and the Socialist Party cried foul, asserting that the results did not accurately reflect the will of the people. Protests erupted across the nation as Actionists and Socialists took to the streets to voice their outrage. The piazzas and boulevards became arenas of dissent as citizens from all walks of life united in their demand for justice and fairness. Banners waved, slogans echoed, and impassioned speeches resounded through the air, creating a cacophony of discontent.

The allegations of vote rigging were at the forefront of these protests. Suspicion had swirled around the election process for weeks, fueled by whispers of irregularities and manipulation. Stories of tampered ballots and suppressed voices spread like wildfire, further stoking the flames of dissent.

The government's response to the protests was swift and severe. Authorities cracked down on demonstrators, attempting to quell the unrest with force. Tear gas filled the air, and clashes between protesters and law enforcement became increasingly common. The nation teetered on the edge of chaos as the discontent and frustration of the people reached a boiling point.

As the November sun dipped below the horizon, Giacomo, an art student from Turin, felt a surge of excitement coursing through his veins. Having recently relocated to Milan, the narrow streets were alive with anticipation as if the very cobblestones beneath his feet were poised for change. He was but a young man, barely in his twenties, yet his heart thumped with the conviction of a lifetime. He recorded his experience in his diaries:

“I had grown up in the shadow of hardships that had befallen his family's humble farm. Rising land rents and oppressive local taxes had cast a heavy burden on their shoulders. It was a burden shared by countless others, those who tilled the soil and toiled beneath the unforgiving Sicilian sun. These struggles had shaped his worldview, and I was determined to make my voice heard.

That evening, as I joined the throngs of fellow protesters, I felt a profound sense of unity - a renewed risorgimento. The purpose rosette I pinned to my chest having been given it by a passer-by bore the emblem of the Fasci, a symbol of our collective hope. Together, we were more than just individuals; they were a force, a chorus of voices demanding justice.

The streets echoed with chants and slogans, resonating with the grievances of the marginalized. I marched alongside my comrades, my determination unwavering. The evening air was charged with tension, yet there was an undeniable sense of purpose that bound us together.

As the demonstration swelled, I couldn't help but glance at the historical buildings that lined the streets. They bore witness to centuries of Italian history, but tonight, they bore witness to something new—an awakening. The purple Actionist flag, a symbol of change, waved proudly alongside the crucifix, a testament to the melding of faith and reform.

But our cries for justice were met with resistance. Giolotti's response was swift and harsh. Suddenly, a loud bang pierced my ears, and I felt a sharp pain shoot up my leg, and I fell, struggling to breathe. I had been hit with grapeshot and was near death. A member of the Fasci picked me up and took me to a doctor who treated my wounds. Another few minutes, he said, and I would have died. At that moment, I knew that I was part of something larger than myself. I was part of a movement that dared to challenge the status quo, a movement that believed in a brighter future. As the protests raged on, I clung to the hope from my hospital bed that their collective voice would eventually break through the barriers of oppression and ring out as a call for change.”

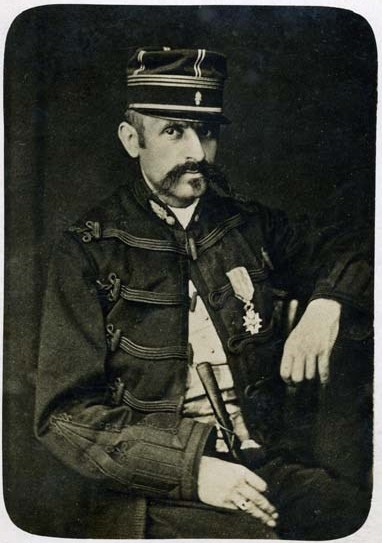

The Giacomo in question? Giacomo Balla, the future leader of Partito d'Azione Italiano. He would forever walk with a limp after the shooting, a distinguishing feature of the man who would haunt the nightmares of the Italian establishment over the next two decades.

Giacomo Balla, the future leader of Partito d'Azione Italiano

As Italy grappled with the aftermath of the November 1892 Election, it was evident that the nation stood at a precipice. The Liberal faction, holding a significant majority in the Chamber of Deputies, would play a pivotal role in shaping Italy's future. Their commitment to cautious progress and reform would guide the nation through the challenges and uncertainties that lay ahead. Yet, this election had laid bare the deep-seated divisions within Italy. The discontent and disillusionment simmering beneath the surface threatened to erupt into something far more destructive. Italy's future appeared increasingly uncertain, and the echoes of a nation teetering on the brink of chaos grew louder with each passing day.

The year was 1892, and the winds of change that had swept across Europe found their way to Italy. The nation's history, like a mosaic of contrasting hues, was about to be painted with the vivid strokes of a new ideology – Actionism. As whispers of revolution and fervent cries for change echoed through the streets of France, the neighboring nation of Italy stood at a crossroads. The land of ancient civilizations and Renaissance art had been grappling with its own set of challenges in the late 19th century. Economic hardships, social disparities, and political upheavals had cast a shadow over the Italian Peninsula.

In the bustling squares of Italy, where oranges hung heavy on the trees, a movement was born. The Fasci Italiano, or Fasci d'Azione Italiano emerged as a beacon of hope for the disenfranchised. Inspired by the revolutionary winds that had swept across France, the Fasci galvanized the poorest and most exploited members of society. They transformed the frustrations and discontent of the masses into a coherent vision of a better future grounded in the establishment of new rights.

Giovanni Giolitti, Prime Minister of Italy

The movement's demands were straightforward – fair land rents, higher wages, lower local taxes, and the equitable distribution of common land. But within these seemingly simple demands lay the aspirations of a marginalized population yearning for justice. From July to October 1892, approximately 170 Fasci were established in Italy. As the movement gained momentum, its membership swelled to over 300,000 by the time November's election loomed on the horizon. Public demonstrations became a constant source of concern for the Italian Government.

The Fasci was a federation of various associations encompassing farm workers, tenant farmers, small sharecroppers, artisans, intellectuals, and industrial laborers. They came together under the banner of change, their unity symbolized by the bundle of sticks – "Fascio" – signifying that while a single stick may break, a bundle was unbreakable.

Amidst the tumultuous sea of political ideologies, the Italian Fasci carried a unique perspective on Actionism. Many of its leaders were devout Catholics, and this infusion of faith into their movement lent it a distinct character. In their meeting halls, crucifixes hung alongside purple Actionist flags, and portraits of revolutionaries like Garibaldi, Mazzini, Sorel, and Marx adorned the walls.

Their conviction led them to proclaim, "Jesus was a true socialist and wanted just what the Fasci were demanding."

As the November 1892 Election drew near, Italy found itself standing on the precipice of change. The conditions leading up to the election were far from ideal. The working class, a significant segment of the population, remained excluded from the electoral process. The contesting parties included the Liberals under Giovanni Giolitti, the Right led by Antonio Starabba di Rudinì, and the Radicals headed by Felice Cavallotti. Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, now at the helm of the Italian Government, faced the daunting task of guiding the nation through these turbulent waters.

Beyond Italy's borders, the nation's allies, Germany and Britain, watched with keen interest. As members of the Accord powers, they both had a vested interest in Italy's stability. The outcome of the election held the potential to not only reshape Italy's domestic landscape but also influence its diplomatic relationships. Within the political spectrum, another new movement was brewing. The Social Democratic Party of Italy, founded in 1892 as the Party of Italian Workers, aligned itself with the principles of Pactism. This movement stood in stark contrast to the Actionists, condemning their deviation from the ideals of Pactism. In the midst of Italy's political maelstrom, the PSI sought to carve out its own path.

Amidst the fervor of the Fasci's emergence, Italy hurtled toward a pivotal moment in its history. As the nation grappled with newfound hope and mounting tension, the stage was set for the November 1892 Election, an event that would both test and redefine the nation's political landscape. The nation was poised for transformation, and the choices made in the coming days would shape its destiny. The storm of Actionism had arrived, and Italy was about to be swept up in its tempestuous embrace.

The sun hung low in the sky, casting long shadows across the Italian Peninsula as the nation held its collective breath, awaiting the outcome of the pivotal November 1892 Election. This election was not just a contest between political parties; it was a referendum on the path Italy would tread. As the results of the election slowly unfolded, they painted a bleak and revealing picture of Italy's political landscape. The new composition of the Chamber of Deputies did little to alleviate the growing tensions within the nation.

The Liberal faction emerged as the victor, but their victory was hardly a resounding one. Securing 369 seats, they had garnered the largest share, yet it was evident that Italy was not embracing their vision with open arms. Their message of moderation and gradual reform had, at best, struck a cautious chord with the voters. The Right managed to secure 76 seats, a testament to their unyielding conservatism. Still, their ideals faced an uphill battle against a changing political climate, and their influence seemed to wane. The Radicals found themselves with 63 seats. Their vision for radical change, though passionate, had failed to ignite a widespread fervor among the electorate.

However, the election was marred by controversy and allegations of vote-rigging and manipulation. In fear of Actionist sympathisers gaining seats in the Chamber, Radicals were arrested prior to the election and found themselves harassed and oppressed by the police. Key Actionist and Socialist figures were targetted also, and the Government resorted to vote rigging to ensure they retained their majority, with the tacit approval of the King and the Accord Powers, who wished to prevent the Actionist revolution from spreading to the Italian Peninsular.

Accusations of irregularities echoed across Italy, casting a long and dark shadow over the electoral process. Both the Fasci and the Socialist Party cried foul, asserting that the results did not accurately reflect the will of the people. Protests erupted across the nation as Actionists and Socialists took to the streets to voice their outrage. The piazzas and boulevards became arenas of dissent as citizens from all walks of life united in their demand for justice and fairness. Banners waved, slogans echoed, and impassioned speeches resounded through the air, creating a cacophony of discontent.

The allegations of vote rigging were at the forefront of these protests. Suspicion had swirled around the election process for weeks, fueled by whispers of irregularities and manipulation. Stories of tampered ballots and suppressed voices spread like wildfire, further stoking the flames of dissent.

The government's response to the protests was swift and severe. Authorities cracked down on demonstrators, attempting to quell the unrest with force. Tear gas filled the air, and clashes between protesters and law enforcement became increasingly common. The nation teetered on the edge of chaos as the discontent and frustration of the people reached a boiling point.

As the November sun dipped below the horizon, Giacomo, an art student from Turin, felt a surge of excitement coursing through his veins. Having recently relocated to Milan, the narrow streets were alive with anticipation as if the very cobblestones beneath his feet were poised for change. He was but a young man, barely in his twenties, yet his heart thumped with the conviction of a lifetime. He recorded his experience in his diaries:

“I had grown up in the shadow of hardships that had befallen his family's humble farm. Rising land rents and oppressive local taxes had cast a heavy burden on their shoulders. It was a burden shared by countless others, those who tilled the soil and toiled beneath the unforgiving Sicilian sun. These struggles had shaped his worldview, and I was determined to make my voice heard.

That evening, as I joined the throngs of fellow protesters, I felt a profound sense of unity - a renewed risorgimento. The purpose rosette I pinned to my chest having been given it by a passer-by bore the emblem of the Fasci, a symbol of our collective hope. Together, we were more than just individuals; they were a force, a chorus of voices demanding justice.

The streets echoed with chants and slogans, resonating with the grievances of the marginalized. I marched alongside my comrades, my determination unwavering. The evening air was charged with tension, yet there was an undeniable sense of purpose that bound us together.

As the demonstration swelled, I couldn't help but glance at the historical buildings that lined the streets. They bore witness to centuries of Italian history, but tonight, they bore witness to something new—an awakening. The purple Actionist flag, a symbol of change, waved proudly alongside the crucifix, a testament to the melding of faith and reform.

But our cries for justice were met with resistance. Giolotti's response was swift and harsh. Suddenly, a loud bang pierced my ears, and I felt a sharp pain shoot up my leg, and I fell, struggling to breathe. I had been hit with grapeshot and was near death. A member of the Fasci picked me up and took me to a doctor who treated my wounds. Another few minutes, he said, and I would have died. At that moment, I knew that I was part of something larger than myself. I was part of a movement that dared to challenge the status quo, a movement that believed in a brighter future. As the protests raged on, I clung to the hope from my hospital bed that their collective voice would eventually break through the barriers of oppression and ring out as a call for change.”

The Giacomo in question? Giacomo Balla, the future leader of Partito d'Azione Italiano. He would forever walk with a limp after the shooting, a distinguishing feature of the man who would haunt the nightmares of the Italian establishment over the next two decades.

Giacomo Balla, the future leader of Partito d'Azione Italiano

As Italy grappled with the aftermath of the November 1892 Election, it was evident that the nation stood at a precipice. The Liberal faction, holding a significant majority in the Chamber of Deputies, would play a pivotal role in shaping Italy's future. Their commitment to cautious progress and reform would guide the nation through the challenges and uncertainties that lay ahead. Yet, this election had laid bare the deep-seated divisions within Italy. The discontent and disillusionment simmering beneath the surface threatened to erupt into something far more destructive. Italy's future appeared increasingly uncertain, and the echoes of a nation teetering on the brink of chaos grew louder with each passing day.

Last edited: