Chapter 21: No terms except unconditional surrender

In January 19th, 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant’s bluecoats approached Fort Donelson, in the Cumberland River. The plan was to cross it and quickly take the Fort. If resistance was found, Grant was to leave a small sieging force while his main army continue forward towards Columbus, where Albert Sidney Johnston’s Confederates were supposed to be. A telegram had already been sent to William T. Sherman’s force, to attack Johnston’s rear. If successful, the rebels could be trapped between the two Federal armies, and thus be destroyed. Knowing this, Johnston had left his position and marched to Fort Donelson, seeking to defeat and drive back Grant and then turn to face Sherman if necessary. Now the two armies were ready to clash.

The decision to fight instead of running like common sense seemed to dictate was a hard one. An important factor was that retreat to Nashville would mean the surrender of Kentucky, President Breckinridge’s home state. The Confederate President naturally loathed the idea of leaving his state alone to the “stern command of the Yankee despot” as he put it. Though he remained for the most part deferent to professional military men such as Davis or the two Johnstons, Breckinridge also wanted to take an active part in the shaping of the national strategy. Personal feelings seemed to cloud his judgement this time; he did not directly order Johnston to attack Grant, but he did ask him to “try and hold my state if it is expedient”.

Johnston telegraphed Breckinridge asking for further instructions. The Commander in Chief decided to ask for the opinions of his General in chief and of Beauregard. Ever aggressive, Beauregard endorsed the idea of attacking Grant and then turning towards Sherman. “We can push the Federal army towards the waters of the Ohio, and make sure that their flag shall never soil Kentucky ever again.” Joe Johnston was far more cautious. His jealousy and distrust of Beauregard may have played a part, but his proposal to simply retreat to Nashville (and perhaps absorb Zollicoffer’s force) was in line with his normal defensive thinking. However, by that time, Breckinridge was already quickly losing faith on him. As a result, he pushed for A. S. Johnston to continue with his plan, and the general put his doubts aside and accepted.

General Sherman’s poor performance at the East Tennessee campaign seems to have also motivated the decision, because it made the Confederates believe that he would not move the army fast enough to attack Johnston, allowing him to freely take on Grant. Sherman’s near mental breakdown raised the rebels’ hope for success.

When he had first came to Kentucky on November, the red-haired Ohioan was ordered by Lincoln to attack through the Cumberland Mountains to relieve East Tennessee’s Unionists. Success at Kanawha apparently emboldened Lincoln, who wanted success there as well to assure the Unionist majority that he thought existed within the Confederacy that Federal arms would back then if they resisted Confederate rule. But Sherman called off the attack at the last minute, panicking about the supposedly overwhelming number of rebels. The fiasco resulted in the lamentable massacre of many Unionist partisans.

The administration showed some clemency towards Sherman thanks to his vital role at Baltimore. But Lincoln demanded action, and so did the Radical Republicans in Congress and many newspapers, which had attacked Sherman by calling him “an insane man on whom command should never be trusted.” Sherman’s angry comment did not help matters, but he caved to the pressure and allowed General George H. Thomas to go forward.

George Henry Thomas was an imposing Virginian who had served with Johnston’s 2nd Cavalry as a major. He had remained steadfastly loyal to the Union, which, naturally, was seen as treachery by the rebels. Serious and phlegmatic, he could never be surprised by anything, be it joyous news or calamitous disaster. Lincoln had at first doubted his loyalty, expecting him to resign like so many other Southerners had done. Sherman, however, assured the Commander in Chief of Thomas’ loyalty. Thomas repaid him with a scare – when Sherman told him the news, Thomas simply said that he was “going South”. Sherman was horrified, until Thomas clarified that he was going South to fight against treason.

At around the same time, the rebels moved towards the Cumberland Gap, the important pass between the mountains. The Confederate commander in charge of securing the area was Felix Zollicoffer, a former newspaper editor from Tennessee who emphatically rejected the saying “discretion is the better part of valor.” For Zollicoffer, valor was more than enough; thus, when he was ordered to Mill Springs, Kentucky, he did not remain south of the Cumberland as military sense might dictate, but rather crossed the river, challenging Thomas’ approaching Federals. Zollicoffer defied his commander, former US Senator Crittenden, and stayed north of the river. Reportedly, he did this because he felt that retreating would be cowardly and unmanly.

Thomas’ advance was slowed down by continuous rain, which he characterized as a “quagmire.” The rebels also suffered many miserable nights, especially Crittenden who felt that destruction was imminent. But after a week, he decided to take a gamble and send Zollicoffer to attack Thomas’ camp at Logan’s Crossroads. In a move that was similar to Johnston’s future plan, he wanted to attack one half of Thomas’ forces, separated from the other by the Fishing Creek, and after victory turn and destroy the other half.

Many factors worked against the Confederates in that day. Bad weather, for one, made the march miserable and difficult, especially for hungry and tired men. Thomas’ vigilant and ready aptitude also allowed his advance cavalry to discover the rebel advance, and have his men ready for battle when Zollicoffer launched the first attack. The Confederate advance soon ran out of steam – many men simply collapsed due to hunger and cold, and others had to retreat because their wet flintlocks would not fire. Thomas led a counterattack that broke the rebels and forced them back. Zollicoffer managed to led them over the river, but he had lost 500 men and lots of precious resources he could not replenish.

Thomas endeavored to pursue him, but the territory south of the river was a barren and cold land with unsuitable roads. Supply would be impossible, and his men were tired too. Always someone who carefully prepared for battle, Thomas did not believe they would be able to beat Zollicoffer’s men, even if they were whipped. Zollicoffer, despite his flaws, was charismatic and grandiose. The Kentucky and Tennessee troops were fiercely loyal, and they actually appreciated his proclamations, such as this call for arms to the Kentuckians: “Kentucky will never endure the destructions of its present social structures until every man has found a heroic death!”

On the Confederate side, an investigation was conducted to determine the blame. Zollicoffer, of course, was in a thin rope due to his insubordinate decision to camp north of the Cumberland. But he managed to pin the blame on Crittenden, even raising rumors that the ex-Senator was a traitor who did not want to fight because his brother was serving in the Union Army. Some men even accused him of being in “an almost beastly state of intoxication” during the battle. A court cleared him of treason, but condemned and demoted him for drunkenness. He would be eventually exiled to the Trans-Mississippi. Zollicoffer, for his part, was ordered to remain near the Cumberland Gap to pin down Thomas, and prevent him from joining Sherman in a possible attack against Johnston.

As for the Union perspective, Thomas’ victory was minor, but it potentially saved Sherman from being stripped of his command, and also was enough to please Lincoln for the moment. The president still wished that a campaign against East Tennessee be recommenced as soon as weather allowed it, and for that he asked Sherman to left Thomas’ army there. He also telegraphed Lyon and Sherman, reminding them that while the Confederates might have an advantage due to their capacity to shift troops through their interior lines, the Union had greater numbers and should use them to pin enemy troops and launch attacks at the same time. If successful, attacks of this nature would negate the Confederate advantage and stretch their already thin forces even thinner. Basically, the President asked his commanders to answer to Southern “concentration in space” with “concentration in time.” Nonetheless, he expressed some doubts to newly minted Secretary of War Stanton concerning Sherman’s panicky estimations of numbers.

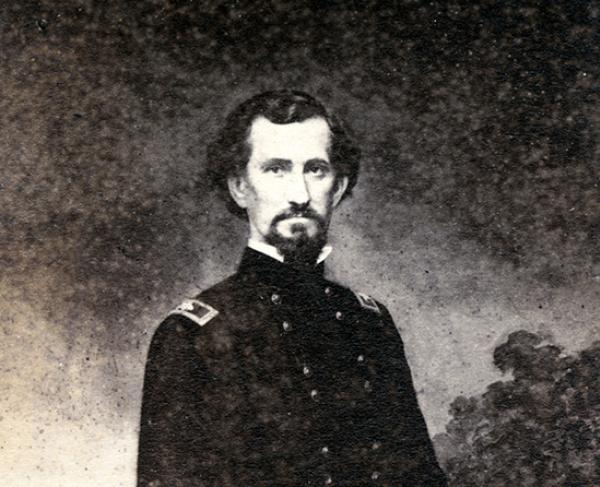

In any case, the pieces were set for the confrontation. Johnston did not feel assured, however. For one, “Fort” Donelson could rather be described as a stockade formed by tents, and protected by artillery and trenches. Johnston had left 10,000 men there. Their objective was to pin a (hopefully large) part of Grant’s force. The defenses, though not really formidable, were expected to last at least some time. Enough at least for the rest of Johnston’s army, right then at the small village of Clarksville, to launch an attack. The commander in charge of the garrison was the mercurial S. B. Buckner.

Named after the legendary Venezuelan liberator Simon Bolivar, Buckner was hardly his namesake’s equal in either ideals or military talent. The first was obvious enough: whatever his flaws, Bolivar had always fought for liberty and despised slavery, while Buckner was fighting for bondage. The second would become apparent after the battle.

Following Lyon’s orders, Grant left around 15,000 men to siege Donelson while he searched for Johnston. Foote, hoping to achieve a success similar to that of Fort Henry, led his flotilla into an attack. Unfortunately for the Federals, the Confederate artillery men were more capable this time. Foote’s ships were unable to knock out even a single Confederate cannon, while these unleashed a volley of artillery that would finally force them to flee. However, and even though rebel morale soared, the defenders were still trapped and surrounded by a superior enemy force. But they had managed their objective of pinning down Union troops – Grant now had only 30,000 men, roughly equal to Johnston’s force. He set to cross the river south of Grant, so that he could surprise him.

But when the time of attack came, Johnston hesitated. His cavalry had been unable to determine whether Sherman was coming in his rear or not. The rebel general was ready to flee to Nashville if that was the case, which would entail abandoning the Donelson garrison. Sherman was dithering, his belief in superior Southern numbers not complete dispelled. Still, had Johnston remained at Bowling Green Sherman would have been there to give him battle; had he retreated to Nashville Sherman would be close enough to join Grant in an attack. It would have been almost impossible for Sherman to arrive at time to take part in the incoming battle. Nonetheless, it’s true enough that his dithering caused a delay.

Now that Foote had been driven away, Johnston finally acted in January 19th. Grant had remained above Fort Donelson, at Dover, waiting for Foote to come back and help him cross the river. Believing that there would be no battle unless he sought it, he instructed the officer holding Donelson, John A. McClernand, t simply hold his position. This would become a constant in Grant’s generalship – he often ignored what his enemies planned to do and focused on what

he was going to do. Though such a pattern made him a dynamic and active general when compared with timid easterners, it also meant that sometimes the enemy could get the drop on him, like it happened at Dover.

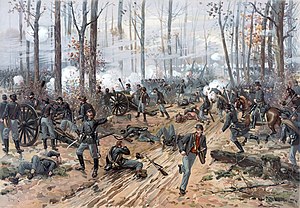

In that day, rebel yells joined the howling winds of winter as the Southerners dashed forward. Johnston did manage to surprise Grant, but the Union general was just as steady and cool as always. He quickly realized that the Federal forces were strong enough to hold the terrain around Dover. That same terrain had allowed the Confederates at Donelson to resist a couple of probing attacks; now, they would allow Grant to resist the rebel advance. Johnston’s hope that the bluecoats’ commander would panic and flee did not materialize.

However, many Yankee boys did flee after all. They had been cocky and confident, despite the fact that almost none of them had “seen the elephant”, that is, actually fought the enemy. Many had heard stories of the carnage at Baltimore, but few could imagine what it really was like. Now they knew, and the experience was not a pleasant one. Many simply fled towards the rear. But this did not result in a Confederate victory, because most Dixie boys were just as scared.

While Johnston and Grant fought it out at Dover, Buckner tried to break-out of the Federal siege at Donelson. With Grant more focused on his battle against Johnston, and not believing that the besieged rebels would take action, he had neglected to give further instructions to McClernand. A political general who believed he ought to command the whole army instead of Grant, McClernand had earned nothing but the distrust of the Ohioan. That may be one of the reasons why he was left in Donelson, instead of accompanying the rest of Grant’s force. In any case, McClernand commanded around 5 brigades in the right of the Union line, where Buckner’s southerners attacked. Though his performance was actually quite good, McClernand was still driven back.

Couriers rushed to find Grant, who could not go there in person. Grant, however, ordered the regiments to the left to join McClernand and retake the position. Those regiments had sat idly on account of Grant’s order to simply hold their positions. They came in time to fill the gap and stop Buckner’s advance. The Yankees then mounted a counterattack that inflicted heavy casualties on Buckner, who was forced back into the fort with a demoralized and weakened force. Some men did manage to escape as a result of the breakout attempt. Among them was the talented cavalry commander Nathan Bretford Forrest, who felt a burning hatred for both Yankees and free Black people. The Yankees, however, were not completely unbloodied. McClernand’s division had been badly whipped, even losing its commander – a stray bullet hit McClernand in the throat, killing him.

The Northerners fought similar success in the North, as Johnston turned cautious again. Perhaps it was fear of losing his reputation, or the reports that Sherman was finally coming. He also feared that Foote would come back and impede a river crossing, leaving him trapped at the wrong side of the Cumberland. That would mean the practical destruction of the Confederacy in the west. In any case, it was clear that Grant could not be broken. With coolness and bravery, Grant personally visited several of his division commanders and rallied back the stranglers. His right flank had been driven back, but General Prentiss’ men resisted bravely. The Confederates launched several disjointed attacks that were all repulsed. The advantage of terrain was especially helpful for the Federals.

Night fell over nightmarish scenes of human suffering and carnage. Wounded soldiers laid in the freezing snow – it is said that some Union and Confederate soldiers huddled together to keep warm. The night was miserable, a night “so cruel, so long” where the only company the soldiers had were the pained groans of their comrades, and the sounds of shelling artillery. Grant and Johnston both, to their credit, had shared their men’s discomfort.

Prentiss salient had resisted defiantly, and Grant maintained his determination. When some officers recommended a retreat, Grant refused: "Retreat? No. I propose to attack at daylight and whip them." Johnston, however, had lost his will. He had lost more men than the Federals had, and the news of the failed breakout attempt at Donelson had badly demoralized his command. More than anything, it seems that Johnston simply was not ready yet for the level of fighting seen that day at Dover. Bloody and terrible fighting had raged all day, wounding and killing thousands. Fighting as terrible as that of Baltimore had finally reached the West.

Grant fulfilled his plan and attacked the rebels at daybreak. The surprised and already depressed rebels were driven back to their original position. Some had hoped that Grant could be pined against the river and destroyed. Now it seemed that

they would have that fate. The Southerners were tired, hungry and cold; Grant’s dashing Yankee boys, smelling victory, were eager to go forward and finish the job. At least some of them were, anyway. Whatever the case, Johnston decided that continuing the fight would only result in their destruction as he expected Sherman to arrive at any time. Some reports given by Forrest also showed that Lyon was sending fresh men from further west. An officer finally asked Johnston whether the men hadn’t had enough, and the general agreed. The rebels finally crossed the Cumberland, ending the battle of Dover.

Grant tried to pursue them, but his men were just as tired and demoralized. Realizing that a pursuit would be fruitless, and content with the victory, Lyon allowed Grant to continue the siege of Fort Donelson. Disgusted with Johnston’s “inglorious flight” and feeling that another attempt at escape would just result in senseless murder, Buckner decided to offer surrender terms to Grant in January 20th. The Confederate maybe hoped that Grant would have some mercy – after all, it was supposed to be a gentleman’s war, and Buckner had even borrowed some money to Grant when he was down on his luck. Only a blunt reply came: “No terms except immediate and unconditional surrender can be accepted.” Though he complained of these "ungenerous and unchivalrous" words, Buckner realized that he had no choice, and he surrendered the men that were left at Donelson.

The Battles of Dover and Donelson made Grant go from an obscure captain to a celebrated war hero in just a couple of days. Northern bells chimed, and cannons gave salutes to the victory. For example, big celebrations were held in Chicago. “Chicago reeled mad with joy . . . Such events happen but once in a lifetime, and we who passed through the scenes of yesterday lived a generation in a day.” The press quickly adopted his words, and even nicknamed him “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, which coincidentally matched his initials. Counting both battles, the Union had lost 1,500 killed, 6,000 wounded, and 2,000 captured or missing, a total of 9,500 men, three times as many casualties as in Baltimore. The rebels fared worse, losing 1,600 killed, 6,200 wounded, and 12,000 captured or missing. Put together, the 19,800 represented a third of Johnston’s force in the Kentucky-Tennessee theater.

A man of honor, Lyon immediately admitted that all the laurels of victory were Grant’s. Lincoln recognized his efforts, and promoted him to Major General, making him only second to Lyon in authority. Lincoln was just was overjoyed as the rest of his people. After months of inaction and disappointment in the east, the news was more than welcome. A lieutenant wrote to Grant, telling him that “Uncle Abe was joyful, and said everything of your boys and spoke of you—in his plain, sensible appreciation of merit and skill.” A certain sense of regional pride seems to have taken over Lincoln, for he also wrote that “if the Southerners think that man for man they are better than our Illinois men, or western men generally, they will discover themselves in a grievous mistake.” Newspapers were also similarly sanguine. The New York Tribune, for instance, declared that "The cause of the Union now marches on in every section of the country. Every blow tells fearfully against the rebellion. The rebels themselves are panic-stricken, or despondent. It now requires no very far-reaching prophet to predict the end of the struggle."

The victory forced Johnston to retreat from Nashville a week after the battle. Despondency took over the people of the city as Johnston announced that he would make no stand to try and hold back Sherman. Perhaps sensing things to come, the soldiers warned the civilians of the “bloodthirsty abolitionists” and said that not even ashes would remain after they passed. Panic spread as everybody who could escaped the city. Columbus was similarly evacuated, and then taken by a Union Army commanded by John Pope. All of Kentucky, and a large part of Western Tennessee (though much to Lincoln’s chagrin, not East Tennessee) came under Union control.

The Battles of Fort Donelson and Dover

The victory also resulted, indirectly, in Sherman being removed as commander of the Department of Ohio. Lincoln was not satisfied with his performance in East Tennessee, and believed that had Sherman been faster, the total destruction of the Confederates would have been achieved. This showed that Lincoln’s strategic thinking had already started to change, since he was focusing on the destruction of the enemy more than in the capture of their cities. Sherman instead was put under Grant’s command, to replace the fallen McClernand as division commander. Unwittingly, Lincoln did great favors to the Union cause for that change allowed Grant and Sherman to meet and form one of the great teams of the war. Lincoln also offered supreme command of the West to Lyon, who refused because he still wanted to keep an eye on his beloved Missouri. Instead, he appointed Don Carlos Buell as commander of the Sherman’s former Department.

While patriotic fervor and joy dominated the Northern press and mood, the Southerners despaired. Newspapers complained of the "disgraceful . . . shameful . . . catalogue of disasters”, while James Mason, minister plenipotentiary to Britain, said that "the late reverses at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson have had an unfortunate effect upon the minds of our friends here.” The demoralizing effect it had in the Southern mind cannot be discounted, for it meant that the Union troops marched with enthusiasm and energy in their next eastern campaign after months where everything had remained all quiet along the Susquehanna.