I'm sure there will be a biography of President Brownlow we'll be able to follow.i may have missed it but how is William Brownlow fairing? If living I’m sure he’s drooling at the fate that awaits the planter class

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"I would vote for you if I lived in Tennessee. That's a winning platform in my book.i really want an absolutely giddy Brownlow to offer a state senate seat , a former slavers mansion , or even to name a city after whoever brings him that devil Forrest so he can watch him squirm while he hangs

And yes he is the only governor whose portrait isn’t in the capitol. Vote for me for governor of Tennessee and I will nail it back up then leave

Ya, the problem even a reformer like Catherine the Great* faced was that basically all of your officers and bureaucrats are minor nobility and the like. Unlike Louis XIV, there is no burgeoning middle class you can draw from. Good luck getting, for example, land reform/redistribution passed when, in addition to fighting the nobility over it, the people who'd implement it are the same ones who stand to lose from it.Lack of land reform in Russia wasn't due to the lack of ideas or the lack of people who were aware that something had to happen. The forces arrayed against it are the reason it didn't happen and those are what need dealing with. Serfdom has only just been abolished TTL and that took over half a century of attempts to finally make stick.

you know who will have fun post war? Cassius Marcellus Clay. From being a slave owner to literally cutting off a pro slavery assassins nose and ears. In our timeline he’s sent to be a minister to Russia but in the post war South here I imagine he’d be a very useful person to have on side

Another fellow who was larger than life. He once held off a pro-slavery mob by firing a cannon at them from his front porch, that's right he had his own cannon. And that wasn't the wildest thing he ever did.you know who will have fun post war? Cassius Marcellus Clay. From being a slave owner to literally cutting off a pro slavery assassins nose and ears. In our timeline he’s sent to be a minister to Russia but in the post war South here I imagine he’d be a very useful person to have on side

Ever you're in Richmond KY, you should visit his home, White Hall, which is open to the Public. It is worth the trip.

Last edited:

“For those who believe in neither the laws of god or man I present this argument against slavery” *holds up two pistols*Another fellow who was larger than life. He once held off a pro-slavery mob by firing a cannon at them from his front porch, that's right he had his own cannon. And that wasn't the wildest thing he ever did.

Ever you're in Richmond KY, you should visit his home, White Hall, which is open to the Public. It is worth the trip.

Have Germans/ German units in the Union Army had to deal with the same amount of criticism as they did in our timeline? I know they were blamed in part for Chancellorsville ( unfairly cause a German speaking scout tried to warn hooker but wasn’t believed ) it would be interesting if German service in the war becomes a sort of founding myth for German culture in America and it becomes as part of the cultural fabric as say the Irish or Italian ones

They were also criticized because of Union frustrations with difficulties of enlistment. Sigel in particular was expected to bring lots of Germans to the cause which in IRL... didn't pan out as much as promised.Have Germans/ German units in the Union Army had to deal with the same amount of criticism as they did in our timeline? I know they were blamed in part for Chancellorsville ( unfairly cause a German speaking scout tried to warn hooker but wasn’t believed ) it would be interesting if German service in the war becomes a sort of founding myth for German culture in America and it becomes as part of the cultural fabric as say the Irish or Italian ones

A more radical civil war and a more discredited Chestnut/Copperhead movement could help with that, as German-Americans were historically more politically disengaged or Democrats, so while I can't remember much ITTL about it, they may have seen a higher enlistment and thus a better reputation.

Especially if Red's ideas of Prussia not so quickly dominating Germany comes to pass, then you might see German-American culture survive and prosper for longer. Though admittedly the same political and cultural pressures would still greatly favor assimilation to some extent. Still, a more linguistically diverse US is also one that may have more internal issues on top of the racial divisions and thus be less willing to go into imperialistic adventures down the line.

EDIT: Brainfart, meant Sigel of the "I goes to fight mit Sigel" fame, whose political ambitions and original reputation in the North were... not validated in actual recruitment numbers and success in persuading German-Americans to sign up as much as he promised.

Last edited:

I’ll be honest I never understood Sigel. German troops loved him , he’s expected to get recruits , what did he do pre war that earned that much responsibility and love? His time in the 48 revolution wasn’t anything special if I remember correctlyThey were also criticized because of Union frustrations with difficulties of enlistment. Sigel in particular was expected to bring lots of Germans to the cause which in IRL... didn't pan out as much as promised.

A more radical civil war and a more discredited Chestnut/Copperhead movement could help with that, as German-Americans were historically more politically disengaged or Democrats, so while I can't remember much ITTL about it, they may have seen a higher enlistment and thus a better reputation.

Especially if Red's ideas of Prussia not so quickly dominating Germany comes to pass, then you might see German-American culture survive and prosper for longer. Though admittedly the same political and cultural pressures would still greatly favor assimilation to some extent. Still, a more linguistically diverse US is also one that may have more internal issues on top of the racial divisions and thus be less willing to go into imperialistic adventures down the line.

EDIT: Brainfart, meant Sigel of the "I goes to fight mit Sigel" fame, whose political ambitions and original reputation in the North were... not validated in actual recruitment numbers and success in persuading German-Americans to sign up as much as he promised.

i wonder if Nathaniel Lyons ( RIP ) surviving his original death date helped opinions. Could have sung the praises of the Germans in St LouisThey were also criticized because of Union frustrations with difficulties of enlistment. Sigel in particular was expected to bring lots of Germans to the cause which in IRL... didn't pan out as much as promised.

A more radical civil war and a more discredited Chestnut/Copperhead movement could help with that, as German-Americans were historically more politically disengaged or Democrats, so while I can't remember much ITTL about it, they may have seen a higher enlistment and thus a better reputation.

Especially if Red's ideas of Prussia not so quickly dominating Germany comes to pass, then you might see German-American culture survive and prosper for longer. Though admittedly the same political and cultural pressures would still greatly favor assimilation to some extent. Still, a more linguistically diverse US is also one that may have more internal issues on top of the racial divisions and thus be less willing to go into imperialistic adventures down the line.

EDIT: Brainfart, meant Sigel of the "I goes to fight mit Sigel" fame, whose political ambitions and original reputation in the North were... not validated in actual recruitment numbers and success in persuading German-Americans to sign up as much as he promised.

One-way German Americans can get some good press is to focus on the more competent 48'ers and other German emigres like August Willich, Adolph Von Steinwehr and Hubert Dilger for a start. Willich in the OTL was considered one of the better brigade commanders of the Army of the Cumberland despite being captured at Stone's River in late '62. Von Steinwehr was one of the better division commanders in the 11th corps, his initiative at Wauhatchie was instrumental in helping Orland Smith relieve Geary's understrength division, as for Dilger, he ended up becoming Gen. Sherman's artillerist of choice in the Army of the Tennessee.They were also criticized because of Union frustrations with difficulties of enlistment. Sigel in particular was expected to bring lots of Germans to the cause which in IRL... didn't pan out as much as promised.

A more radical civil war and a more discredited Chestnut/Copperhead movement could help with that, as German-Americans were historically more politically disengaged or Democrats, so while I can't remember much ITTL about it, they may have seen a higher enlistment and thus a better reputation.

Especially if Red's ideas of Prussia not so quickly dominating Germany comes to pass, then you might see German-American culture survive and prosper for longer. Though admittedly the same political and cultural pressures would still greatly favor assimilation to some extent. Still, a more linguistically diverse US is also one that may have more internal issues on top of the racial divisions and thus be less willing to go into imperialistic adventures down the line.

EDIT: Brainfart, meant Sigel of the "I goes to fight mit Sigel" fame, whose political ambitions and original reputation in the North were... not validated in actual recruitment numbers and success in persuading German-Americans to sign up as much as he promised.

Last edited:

Every time I see an alert for this story, I assume there been an update but sadly no

Then someone reads Willich’s pamphlet about closing West Point and reorganizing the army into various local militias where service is a mandatory responsibility and goes “ohhhh boy”One-way German Americans can get some good press is to focus on the more competent 48'ers and other German emigres like August Willich, Adolph Von Steinwehr and Hubert Dilger for a start. Willich in the OTL was considered one of the better brigade commanders of the Army of the Cumberland despite being captured at Stone's River in late '62. Von Steinwehr was one of the better division commanders in the 11th corps, his initiative at Wauhatchie was instrumental in helping Orland Smith relieve Geary's understrength division, as for Dilger, he ended up becoming Gen. Sherman's artillerist of choice in the Army of the Tennessee.

Same. And I’m contributing to the problem but same lolEvery time I see an alert for this story, I assume there been an update but sadly no

Tbf, up until the Civil War began OTL, West Point wasn't known for producing military leaders the caliber one would expect from Sandhurst or St. Cyr. Given Willich's pedigree as a Prussian drillmaster, as Peter Cozzens would put it, his suggestions, if he has a good service record ITTL might get a closer look. Personally, I think it would be fascinating to see northern alternatives to an institution perceived as kowtowing to Southerners along with producing the likes of Lee, Jackson, and both Johnstons.Then someone reads Willich’s pamphlet about closing West Point and reorganizing the army into various local militias where service is a mandatory responsibility and goes “ohhhh boy”

Me as well. I mean, I actually like the discussions in this thread. They can be interesting at times, but yeah.Lisowczycy said:

Every time I see an alert for this story, I assume there been an update but sadly no

And that could have some interesting implications later on regarding exiled leaders and whether governments have a right to ask for their extradition or not, now you mentioned it.That would open pretty interesting questions in international law regarding who is considered a "legitimate" refugee.

Or if , fingers crossed , he plays a big part in reconstruction. Let him open one down there. Half military academy half political education. Reconstruct the South with class solidarity as its baseTbf, up until the Civil War began OTL, West Point wasn't known for producing military leaders the caliber one would expect from Sandhurst or St. Cyr. Given Willich's pedigree as a Prussian drillmaster, as Peter Cozzens would put it, his suggestions, if he has a good service record ITTL might get a closer look. Personally, I think it would be fascinating to see northern alternatives to an institution perceived as kowtowing to Southerners along with producing the likes of Lee, Jackson, and both Johnstons.

Last edited:

Chapter 55: It Must Be Now that the Kingdom's Coming

The new Provisional Government of the Confederate States was in many ways an astounding departure from the traditional American ethos that had defined the South as much as the North. Several Founding Fathers who were now claimed by the Confederacy, including the Virginia slaveholders George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, had all opposed military government and sincerely supported republican institutions. But in truth, these people also considered democracy to be as terrible a tyranny as monarchy. For Madison, a republic ought to “protect the minority of the opulent against the majority,” while Washington had once warned of “mob, or Club government,” and acted decisively to crush the Whiskey Rebellion. As President, Jefferson, having long abandoned his earlier idealism, denounced the Haitian revolutionaries as the “Cannibals of the terrible republic,” and warned that if Americans didn’t act against slave revolts they would “become the assassins of our own children.” Their American Republic was about protecting liberty as much as protecting the right to rule of the wealthy and virtuous elite.

The Confederate Counterrevolutionaries thus could claim that they were not abandoning the values of 1776 but saving them. Faced with defeat, they felt they truly had no option but to depose their own leader and engage in a last-ditch effort to save slavery, White supremacy, and aristocratic rule from the Union’s frightening emancipation, equality, and a democratic government that included Black men. A soldier so informed his fiancée, saying he supported the coup because he wanted them to live under “a free white man's government instead of living under a black republican government,” while an Alabamian, at the same time as he invoked Washington’s “example in bursting the bonds of tyranny,” boldly said they had to “fight forever, rather than submit to freeing negroes among us.” Such a fate would be rendered even more terrible if it was the result of ignominious surrender. Breckinridge had to be overthrown, the Charleston Mercury justified, because he sought to transform the South into “a mongrel, half-nigger, half white-man, universal freedom, beggarly Republic not surpassed even by Hayti.”

Some went even farther, most notably George Fitzhugh, who denounced the “pompous inanities” of the Declaration of Independence as the work of “charlatanic, half-learned, pedantic authors,” who believed the “infidel doctrine” that “all men are created equal.” Frankly categorizing the Southern Counterrevolution as “reactionary and conservative,” Fitzhugh advocated for rolling back “the excesses of the Reformation . . . the doctrines of natural liberty, human equality and the social contract.” The Gholson report that so bitterly denounced Black recruitment similarly directly warned that a “Democratic Republic without the balance wheel, which our disfranchised laboring class affords must soon degenerate as the experience of the Northern states has proved, into a Mobocratic despotism.” Even fiery nationalists like the writer Augusta Jane Evans confessed being “pained and astonished” at “how many are now willing to glide unhesitantly into a dictatorship, a military despotism.” Pushed to choose, committed Confederates preferred dictatorship to affording Black people liberty and rights.

This is not to say that the coup enjoyed unanimous acceptance from all Southerners. But in the Army, where the ardor for the cause was most pronounced, the new government received initial wide support. Chiefly, there was the fact that they didn’t feel themselves defeated yet, and believed that to surrender would be a stab in the back that would render all previous sacrifices meaningless. “We should yield all to our country now. It is bigger than any singular despot,” exclaimed a North Carolinian. “We must triumph or perish.” A soldier expressed likewise that he preferred to “die fighting for my country and my rights,” rather than in “dishonorable surrender.” And, having seen “the hireling horde” slay so many “who are striking for their liberties, homes, firesides, wives and children,” a Virginian resolved that they would never allow “the chivalrous Volunteer State to pass under Lincoln rule,” as “the traitor Breckinridge wanted.”

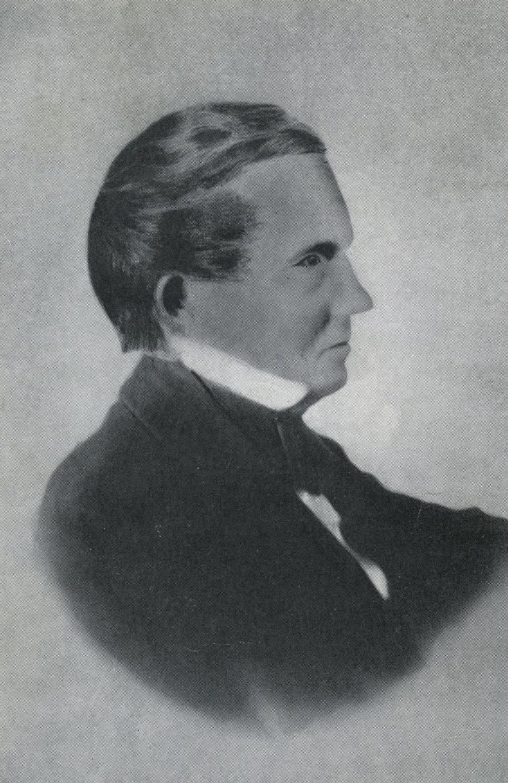

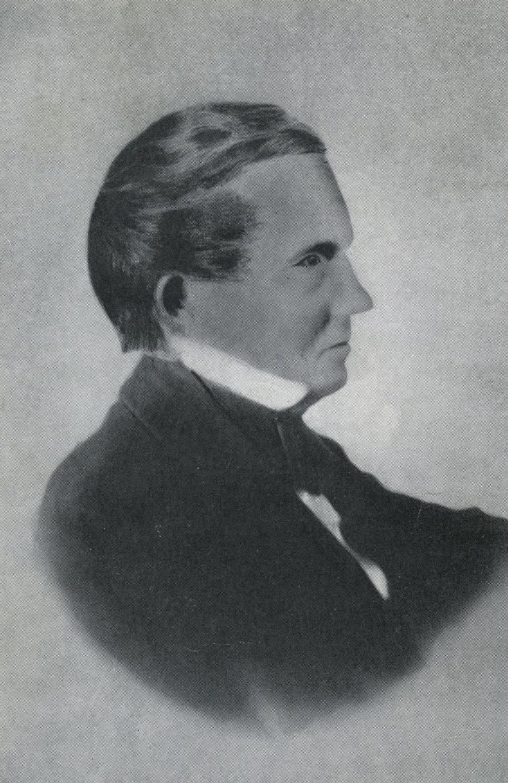

George Fitzhugh

The attempt to arrest James Longstreet shows the initial wave of support for the coup. The same day Breckinridge was arrested, a courier in a lathered horse arrived. Longstreet at first believed that Grant was attacking, but the courier informed him that “it is General Jackson who has attacked the government.” Longstreet stood there for impossibly long minutes, not comprehending what he was hearing. Finally, he sat down and covered his face with his hands. “I suppose,” he said, “that this is the end of the Confederacy.” Longstreet then stood up, rummaged through his bearings for a white rag, and then said to his staff “Gentlemen, I’m afraid I’ll have to try my chances with General Grant. I know Jackson will have me shot, I can only hope Grant won’t.” Several of the men then pleaded with him, to either try and march his soldiers to Richmond to prevent the coup or even swear loyalty to the new government, but Longstreet shook his head. “Nothing will induce me to fire on other Southerners,” Longstreet said, his voice now choked. “And, as far as I’m concerned, there is no Confederate government anymore.”

Just before the arrival of a regiment under Jackson, Longstreet and a small party escaped to Federal lines and surrendered to Grant, while most of the soldiers in Peterburg cheered Jackson’s arrival and “called for the blood of the traitor Longstreet, who was going to betray General Lee by surrendering our city to the abolitionists,” reported an officer. This reveals another reason for supporting the coup – the belief that doing so would best preserve and honor Lee’s memory. Junta supporters again and again emphasized the “indomitable valor” of Lee, insisted that the late General “would never contemplate or allow the abashment and disgrace of surrender,” and posited that Lee himself would have overthrown Breckinridge had he lived. History has been unable to agree on interpreting Lee’s actions, his loyalty to Breckinridge and general pessimism in the last months clashing with a sense of duty and certain refusal to accept defeat. But at the time, among the soldiers the general conviction was that Lee would have wanted them to continue fighting. “I am doing this for Marse Lee and Virginia, not for that dammed Toombs,” explained a private to his sister.

Longstreet’s decision to flee would soon prove wise, as shown by the unhappy fate of General Cleburne. Appointed to lead a united “Army of Georgia” following the disaster at Atlanta, Cleburne was arrested by his own troops, who now derided him as the “architect of Breckinridge’s Negro policy.” Cleburne tried to resist the arrest, and rally men to his defense, but they shouted him down, calling him a “Nigger lover.” While trying to escape, Cleburne was shot and killed. A few days later, Johnston returned, having regained command of the Army as a reward for his role in the coup. He announced that “the traitors in the government that betrayed you” had been removed, and now “we the patriotic men of the South are ready to abandon their ruinous policies and lead you to a final triumph.” Loud cheers for Johnston, and for Toombs and Jackson, followed the proclamation. And those who doubted were unable to raise their voices over this fervent, desperate delusion.

Some have blamed the coup’s success on the supposed cowardice of men like Longstreet, who preferred flight to fight. Asked why he didn’t stand by Lee after the war, Longstreet replied icily that “General Lee was dead.” Longstreet maintained to his dying breath that Lee would have never betrayed Breckinridge, and that a countercoup could only “unleash the evils of fratricide within the Southern armies.” This was shown by the Orphan Brigade, which conspired to try and stage a mutiny to free Breckinridge. Their efforts floundered, mostly because Breckinridge himself opposed any kind of revolt. Instead, many ended up deserting, and it is said that when the news that Breckinridge would be trialed were announced many men threw down their arms on the spot. The fears that the Brigade or other regiments would act justified for the Junta the decision to execute Breckinridge. Similar fears motivated the start of a purge of “Breckinridgites” in the Army and government.

Some allies of Breckinridge, including many of the advocates of Black recruitment and the staff of the de facto administration organ the Richmond Sentinel, were arrested the same day as the former President. Within the former Cabinet, only Campbell was executed, while trying to flee, while the rest was sent to military prisons – the Junta being actually gracious enough to place the sickly George A. Trenholm under house arrest. But perhaps the greatest show of the Junta’s new direction was the events in Congress. Meeting under the watchful eye of Jackson’s soldiers, the remnants of the Congress were barely able to muster up a quorum, for several Nationalist legislators had been arrested and others fled. A bill was immediately proposed to recognize the Provisional Government. Senator Wigfall stood up then. While he denounced Breckinridge’s “tyranny & reckless disregard of law and contemptuous treatment of Congress,” Wigfall insisted that there was no legal basis for a Provisional Government. Even if “the urgency justifies setting aside the forms of law,” the proper course was for Stephens to assume the Presidency.

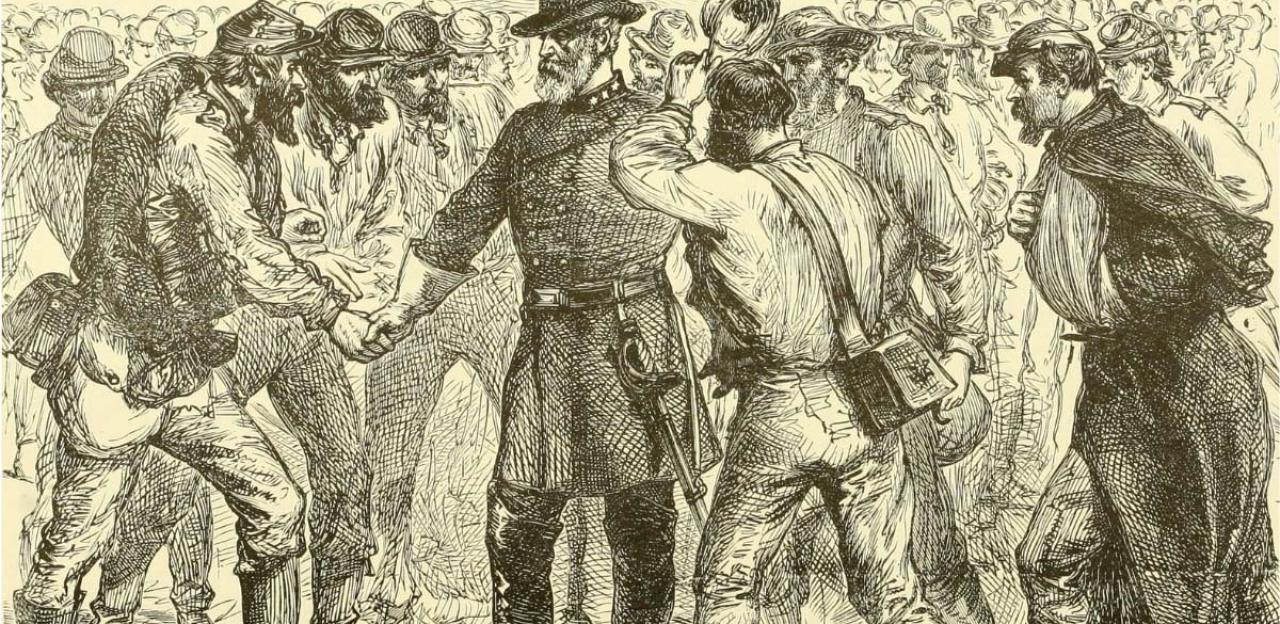

Pushed to choose between their President and what they believed to be their General's legacy, the soldiers chose Lee

Stephens himself would raise that point shortly. He furthermore opposed the formation of the ad hoc tribunal that tried Breckinridge and Davis, proposing they be judged by ordinary Virginia courts instead, and was the only member of the Junta to openly speak against their execution – though mostly on the basis that the Confederate government had no legal authority to execute any civilian. Wigfall’s and Stephens’ arguments threatened the security of the Junta, and Wigfall would soon be arrested while a disillusioned Stephens would leave Richmond less than a month after the coup. Soon, a Congress without quorum voted on the resolution granting post facto legitimacy to the Junta and then voted to adjourn. The Confederate Congress would never meet again. From his home in Georgia, Stephens denounced the Junta as a “Mexicanization” of politics that “has shown itself to be an even worse tyranny.” But whereas Breckinridge’s “despotism” was always denounced openly, Stephens prudently said nothing publicly, staying home until Union forces arrested him after the end. “Toombs is now dictator,” Stephens wrote sadly in his last day in Richmond, “and all hopes are gone.”

Not all Confederate politicians and soldiers were willing to back the coup, however. General Kirby Smith, the practical commander in-chief of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi, denounced the coup as an act of “usurpation” and refused to follow its orders, releasing a proclamation where he declared Stephens the legitimate President and said he would only obey orders from Congress. After Breckinridge’s execution and the dissolution of Congress it dawned on Smith that that there was little hope of a countercoup, and that Stephens was completely uninterested in opposing the Junta. Accordingly, Smith declared he would act independently of Richmond and in coordination with the almost defunct State governments in his department, until the Congress reconvened or a new one was elected. For all intents and purposed, Smith had become a warlord.

Smith’s decision was not so much based on personal loyalty to Breckinridge. In fact, Smith was something of a dead-ender too. Rather, it was based on an opposition to the leaders of the Junta as a “band of rascals and failures,” and the realization that the coup had gutted the legitimacy of the government. A similar reasoning led General Taylor and the Native American General Stand Watie to pledge the loyalty of their remaining forces to Smith rather than Toombs. Far different was the reaction of John Singleton Mosby, who was genuinely loyal to Breckinridge and surrendered himself, alongside around a third of his partisan force, to Grant, claiming there was “no government we owe allegiance to anymore.” For their part, the forces under Sterling Price in Missouri and Kansas, and those under Forrest in Tennessee and Northern Mississippi, all also refused to heed the Junta, but did not pledge loyalty to anyone else either. Thus, all these commanders became in essence guerrilla bands, and have been labelled as the “Confederate warlords.”

A furious Toombs threatened to have Smith and all who followed him trialed as traitors, but he was conscious of the fact that the effective power of his new government did not extend much farther than the territory under the control of the Armies of Georgia and Northern Virginia. However, the Junta still repressed dissent harshly, closing critical newspapers and executing scores of soldiers who wanted to desert, including the last remnants of the Orphan Brigade. Such events allowed the opponents of the Junta to talk of a “generalized purge and reign of terror.” In reality, the purge was a rather superficial one. The majority of the bureaucracy and civil officials of the Confederacy retained their posts, and government routine was not greatly disrupted. Even John Jones, an ardent Breckinridgite, was not ever bothered by the new regime, leading him to comment that “the events following the revolution against Mr. Breckinridge have seemed like a most surreal dream.” This answers to the counterrevolutionary nature of the coup, for similarly to secession it was executed mostly to prevent the adoption of measures opposed by the South’s leaders, rather than to adopt new measures themselves.

Another aspect in which the Junta was similar to secession was its quick and decisive execution, meaning that many Southerners were simply confronted by a fair accompli when they first learned of it. Among most planters the reaction was support, even if it sometimes was qualified. On one side Catherine Edmonston cheered the remotion of “our Congress, our public men, our President & his imbecile Cabinet,” for “They it is who have beaten us,” and expressed confidence that “this is the inauguration of a period of victory and rights.” At the other extreme Mary Chesnut condemned the coup as “black treason,” and said she “wept bitterly for our gallant leader. Why is it that the best of us are victims of the worst betrayals?” Chesnut’s opinion, however, was certainly influenced by the fact that her husband had been arrested for having served as an aide to Davis. Nonetheless, the great majority of those who opposed the Junta did not dare say anything. Senator Graham, for example, privately wanted Stephens to assume the Presidency and arrange a peace, albeit one that preserved slavery. Graham thought the coup “an act of treachery and imbecility,” but said nothing publicly.

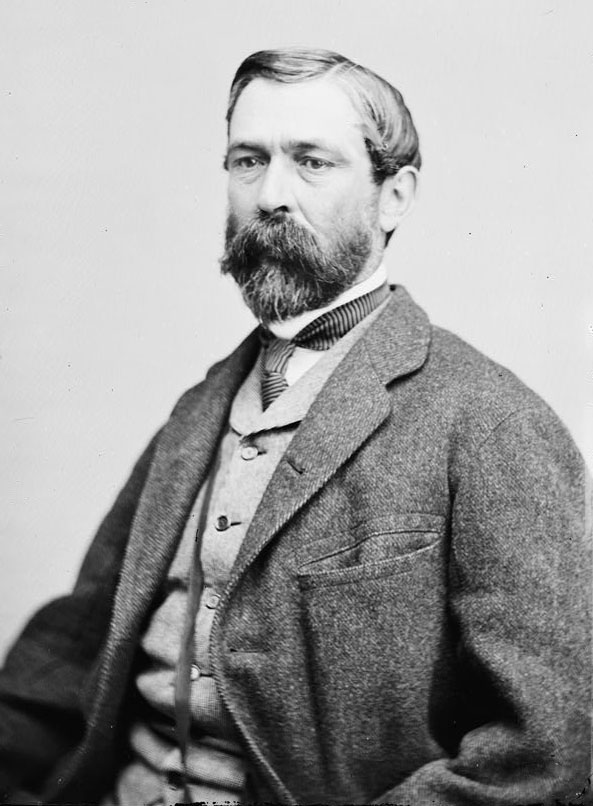

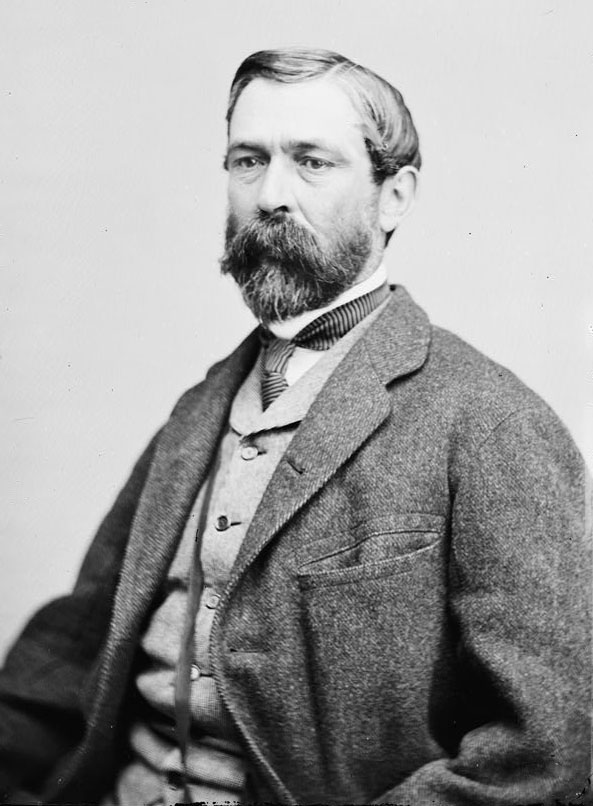

Richard Taylor

Other members of the planter elite preferred to hide in blissful ignorance, ignoring both the coup and the Yankees. “Never were parties more numerous,” reported an Alabama newspaper. “The love of dress, the display of jewelry and costly attire, the extravagance and folly are greater than ever.” The South Carolinian Grace Elmore believed that this “utter abandonment to the pleasure of the present” was the only way of “shutting out for the moment the horrors that surround us.” With almost tragic insight, Katherine Stone observed that the planter aristocracy lived “the life of the nobility of France during the days of the French Revolution—thrusting all the cares and tragedies of life aside and drinking deep of life’s joys while it lasted.” If the Junta had failed to raise their morale, it hadn’t spurned them to act against it either, for “the situation has not changed, not at all – we are still going down in disastrous defeat,” as one man explained. “So, why should we bother?”

Among many Southerners outside the political and economic elite, the reaction was a mix of initial shock and apathy. As a Federal officer observed later, “it is exceedingly hard for the common people to care who their next leader will be when they must wonder what their next meal will be instead.” The anger and bitterness that would settle in later took some time to materialize. This is owed, again, to the counterrevolutionary nature of the coup – whereas Breckinridge’s decrees had been opening new terrifying possibilities such as Black recruitment and a return to Union rule, the Junta seemed, by contrast, a return to the status quo before Atlanta’s fall. A Georgia community, for example, celebrated when Black slaves pressed into military service were shackled and returned to their slavers. By promising victory without Black recruitment and blaming all that had gone wrong in the previous administration, the Junta revitalized the hopes of many Confederates, who clung to the idea that they could yet seize victory from the rapidly closing jaws of defeat.

“Never before has the war spirit burned so fiercely and steadily,” claimed the Richmond Dispatch, commenting on the supposed uptick of morale. Josiah Gorgas, retained in his post due to his talents, also said that “The war spirit has blazed out afresh.” Only later would the Dispatch admit sullenly that this was nothing but “a spasmodic revival, or short fever of the public mind,” that left among the people only “a dull, helpless expectation, a blank despondency.” But at the time, the Junta insisted that things would soon turn for the better, and gleefully printed reports of men returning to the Armies based on a general amnesty. To try and show the people that the situation was improving, the Junta opened the food stores Breckinridge had been saving for the winter and for food relief and used the Treasury’s dwindling specie to pay some salaries. For those who paid attention, however, the Junta’s real priorities were clear, for far more specie was used in paying slaveholders back for the human chattel Breckinridge had taken.

Initial sanguine expectations proved wildly mistaken, as the Junta failed to raise either more men or material. Some planters, trying to prove Toombs’ argument that the slavocracy would be glad to offer anything if only the government removed its heavy hand, had indeed donated supplies and food to the hungry. But the majority preferred to simply save their property for themselves and for profit. The Junta, too, realized that its most ultra demands such as an end to the draft and impressment were simply unpracticable, and while assurances flowed from Richmond that those policies would soon end the government just continued them. Even worse, they sought to “equalize” the burden by requiring the poor people to contribute as much as the planters, whereas Breckinridge had always tried to impress more from the rich.

Especially during the winter, poor Confederates started to feel the effects of the Junta’s pro-planter policies. Breckinridge’s food relief corps had never been able to completely stave off hunger, but the program was completely abandoned after the coup, bringing entire towns perilously close to starvation. The revocation of Breckinridge’s decrees had, furthermore, freed food and supplies that had been taken from planters with the purpose of feeding the common folk, allowing them to sell these goods at inflated prices instead. Some communities would even remember landowners burning food crops Breckinridge had forced them to plant, naturally after reserving a portion for themselves, all so they would have more land for cotton or other more profitable crops. “The sight of the burning green maize and potatoes caused a ripple of despair in all of us,” a man remembered after the war. “In that bonfire our last hope was turned to ash . . . It was the same as if they had burnt our children alive.”

The actions of the Junta only worsened the food situation in the South

Throughout the final months of the Confederacy, as they observed the planters receiving their slaves back, being given specie for the damages, and being asked less in taxes or impressment, opposition to the Junta and a new rose-tinted view of Breckinridge’s regime started to take hold among the poor. “The cry from every person is, ‘these abuses would not be if only Breck were here!’” said a Virginia yeoman. It is true that Breckinridge had been already rather popular with many poor Southerners who thought of him as their defender. But just as many identified him instead as the man who took their sons and husbands, and the willing tool of the planters. This negative opinion was virtually destroyed by the coup, for in the minds of many of the disillusioned Breckinridge transformed from an ineffectual leader to a martyr, first thwarted by disloyal subordinates and then murdered by them. As the situation grew more desperate, the flames of discontent would grow wilder and stronger, until social order started to break down.

The plight of the poor was easy to ignore at first, however. Since the people most likely to oppose the Junta from the start were those with the lowest commitment to the Confederacy, men who likely had already deserted and who had opposed Breckinridge too, their alienation did not truly result in any loss of strength for the Confederacy. All “gentlemen” supported the new government and only the “riff raff, the off scouring of society” opposed it, Edmonston sniffed. “Fondness for the traitor Breckinridge’s atrocious and criminal regime,” a newspaper claimed, could only be found among “the miserable cutthroats and wretched fools” that thought that “impressment meant the liberty of robbing their betters.” No wonder, then, that few of the common people who had come to oppose the Confederacy before the coup returned to the Army after it, and that within many communities opposition to the war and the Confederacy remained as strong as ever. “We don’t give a damn whether the order comes from Breck or Bob, we shall not go,” defiantly declared an upcountry Georgian.

Indeed, some Southern Unionist celebrated instead, identifying Breckinridge as the tyrant who had oppressed and massacred them before, not as an unjustly deposed savior. “We shout for joy that the Ceasar has fallen!” a meeting in western North Carolina resolved. “And we pray that the Brutus and Cassius shall follow him soon.” Amidst African American there also were spontaneous festivities, which many planters allowed under the mistaken belief that this showed support for the Junta and a “desire to stay under our care,” instead of being taken by Breckinridge. A freedman later mocked masters for this naivete, stating that the enslaved “knew the Southern government was no more, and if there not be one there not be slavery.” A more perceptive South Carolina mistress realized this, concluding that the people she enslaved “think this can only help them, and they expected for 'something to turn up.’”

With no real plan or interest for conciliating the people, a newspaper was forced to ask Southern ladies, especially “the younger portion of them . . . to treat the renegades with the scorn they deserve; to drive them back to their colors with the scorn which nobody but a woman knows how to manifest.’’ When such appeals failed, it was easy for the Junta to turn to terror again. In fact, it had never really stopped, for the decentralized nature of Southern repression meant that the Army and militia units that had been engaged in suppressing Unionism and dissent just continued after the coup. Nonetheless, the fact had been that Breckinridge was never comfortable with such violent tactics and actively opposed war crimes, which had somewhat tempered their excesses. But the Junta granted them carte blanche, soon resulting in appalling and bloody consequences.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup few could foresee that the Junta was only leading them to a more catastrophic defeat. A majority of Southern Whites remained desirous of a victory that could secure slavery and White supremacy, had loathed Breckinridge’s decrees and blamed him for the late defeats, and convinced themselves that the Junta would somehow turn things around. The reaction was especially positive within the State governments that had led and encouraged the resistance to the Breckinridge administration and its hated measures – mostly because the Junta basically allowed them to do anything they wanted. Governor Vance thus withheld “from the Army 92,000 uniforms and huge stores of blankets and shoe leather, reserving the lot for his North Carolina militia,” while Governor Brown recalled the 10,000 men militia that had been attached to the Army of Georgia and called for “all the sons of Georgia to return to their own State and within her own limits to rally around her glorious flag.”

Repression of Unionism would continue and intensify after the coup

The Junta thus presided over a decentralization of Confederate war policy, allowing State militias under the direction of their State governments to fight alongside the national armies. This would soon result in victories, Toombs optimistically predicted, for it had been Breckinridge’s unconstitutional meddling that had driven people away and impeded the States from bringing their full strength to bear. Toombs even had the gall to declare in a proclamation that the Junta was “restoring to the people . . . rights that had been unjustly usurped,” constituting a “triumphal return to the rule of law and constitutional government.” Initial reports seemed to back this assessment, asserting that hundreds of Georgians and North Carolinians rejoined the Confederate forces, motivated by the defense of their states and the knowledge that they would not be sent elsewhere. Predictably, however, the ultimate consequence of this policy was disaster, as the Army and militia were utterly incapable of coordinating or presenting effective resistance to the Yankee armies. That, too, laid in the future, but the South already was preparing for the Northern reaction.

The coup surprised some Northerners as much as it surprised the Southerners. Following the victories at Atlanta and Mobile, Lincoln and the Republicans could breathe a sigh of relief. “The political skies begin to brighten,” declared the New York Times. “The clouds that lowered over the Union cause a month ago are breaking away.” But if the outlook was sunnier for Lincoln, it darkened disastrously for the opponents of his administration. A New Yorker declared already in early 1864 that the National Union was “in a state of hopeless disintegration.” Yet, the increasing radicalism of the Lincoln administration alongside its decreasing popularity inspired in the opposition the idea that they could rally everyone to their banner. The issue was that there remained several competing banners. Most War Chesnuts, loathing both Republicans and Copperheads, were focused on resurrecting the old Democratic Party. So proclaimed Andrew Johnson, who called on his “old friends of the democratic party proper” to take over the National Union and “justly vindicate its devotion to true Democratic policy . . . established by the apostle of freedom and liberty, Thomas Jefferson, and upheld by the unswerving sage and true patriot, Andrew Jackson.”

Most War Democrats scorned the Copperheads and believed that associating with them would just concede to Lincoln the issue of loyalty. “The Vallandigham spirit is rampant,” they worried, especially after it was discovered that he had secured a seat on the Committee of Resolutions. Acknowledging his weak position in July, however, Vallandigham tried to delay the Convention, all but hoping that the Union’s summer offensives would fail. Instead, Dean Richmond, the chairman of the National Committee, used this opportunity to exclude the Peace Chesnuts and held the meeting at the scheduled date. This, he believed, would allow him to hold the party together, while by waiting they would just allow the divisions to grow wider. Though some Chesnuts flirted with commanders, especially Hancock, when it was clear that there was no general that could be recruited as a viable candidate, they instead turned to Johnson. Characterizing him as a “strong Union Man,” the delegates believed “Old Abe is quite in trouble now” since Johnson’s loyalty was unimpeachable.

At the same time as the National Union split over the division between Peace and War Chesnuts, Samuel Tilden and other New York politicians tried to form their own movement. The former Eastern Democrats had greatly suffered over the Douglas-Buchanan feud, especially because Buchanan remained in control of Federal patronage and due to their dependance of Southern cotton. Douglas’ National Union thus had drawn most of its strength from the West, with most Easterners being skeptical of his ambitions. Though they joined the Chesnuts in the hopes of presenting a united front against Lincoln, some deep distrust subsisted. Republican victories at both the State and Federal levels plus the destructive New York riots had all but annihilated the old Tammany Hall machine, giving rise to a more moderate generation that had felt disconnected from the Western Chesnuts. Further compounding the issue was its intersection with the Republican Party’s own inner feuds, for New York Republicans were also divided between the Radicals that followed Horace Greeley and Governor Wadsworth and the conservative Seward-Weed machine.

A quarrel older than the Republican Party itself, it was only intensified by the war. In 1862, Greeley controlled the Republican nominations, leaving Weed and his allies out. Disgruntled, Weed would do little to help the ticket, and when it obtained a narrow victory the Greeley forces accused Weed of sabotage and refused to extend State patronage to him. The result was a bitter internecine contest that saw Weed trying to take over control of all Federal patronage, focusing on the biggest plum, the Custom’s House. But, in order to secure the loyalty of former Democrats, Lincoln had given most posts there to former Democrats and allowed Secretary Chase to name most appointments. Lincoln’s refusal to turn over control to Weed was considered an “outrage and insult” by the veteran politician, who came to believe that the people had “not had the worth of their Blood and Treasure” from Lincoln’s government. By 1864, observers reported that “old Weed was undoubtedly opposed to Lincoln.”

Edward Thurlow Weed

Lincoln’s own clash with Chase over the Republican nomination made Weed decide to, reluctantly, procure a unanimous vote for Lincoln from the New York delegates. Afterwards, his position now secured, Lincoln rejected to appoint more of Chase’s men, stating in a revealing letter that the fight over the Custom’s House had brought many Republicans to “the verge of open revolt.” Chase tested the President by offering his resignation, but he overplayed his hand for Lincoln finally accepted it. Self-righteously, Chase wrote that this could only be owed to his “unwillingness to have offices distributed as spoils.” To replace Chase, Lincoln appointed Senator William Pitt Fessenden, “who was horrified when he heard the news,” and tried to beg off on account of physical weakness, stating he might die if he accepted. Lincoln and Stanton were both unsympathetic, Lincoln saying “the crisis was such as demanded any sacrifice, even life itself,” while Stanton told him that “very well, you cannot die better than in trying to save your country.”

However, Chase’s removal failed to satisfy Weed, who had grown especially critical due to the failures in the summer of 1864 and Lincoln’s refusal to negotiate any peace that did not include emancipation. Abram Wakeman, the New York postmaster, confessed to being “fearful that our hold upon Mr. Weed is slight.” Their hold was even shakier than Wakeman feared – by July, Weed publicly offered his support to anyone who took as his platform the preservation of the Union without regard to slavery. Tilden and his men, who had conspired months ago to try and commit Lincoln to a more moderate course, swept in and successfully recruited Weed then. Their independence from the Copperheads, with them having refused to attend the National Union Convention, and the support they enjoyed from Conservatives such as the Blairs and John A. Dix made the movement palatable. It culminated in Tilden’s nomination as the candidate of the “National American Party.”

Tilden immediately made entreaties to Johnson, to try and get him to withdraw in order to concentrate against Lincoln. Johnson, however, at first refused. Yet, he had to recognize that to remain divided could only benefit Lincoln. In the meantime, Vallandigham had formed his own convention, showing considerable strength in the Midwest, while military defeats created a growing pressure for peace. Consequently, the idea of uniting against Lincoln seemed both more appealing and more feasible. This resulted in the Second Chicago Convention, where the expectation was for a Tilden-Johnson ticket, standing on a platform calling for negotiations based only in the Union. Yet, even before Atlanta, there were some worrying signs of disunity. Johnson still distrusted Vallandigham, who, for his part, warned Tilden not to listen to “some of your friends who, in an evil hour, may advise you to insinuate war . . . If anything implying war is presented, two hundred thousand men in the West will withhold their support.” Tilden’s brittle alliance with Weed also presented a complication, with Weed warning that any outright Copperheadism would push him back into the Lincoln fold. This was the situation when they received news of Atlanta’s fall, overthrowing all their machinations.

The Johnson men were in an evident sour mood when chairman August Belmont opened the Convention by emphasizing that “four years of misrule, by a sectional, fanatical and corrupt party, have brought our country to the very verge of ruin,” and thus they were not reunited “as advocates of war or advocates of peace, but as citizens of the great Republic.” But any hopes for retaining unity were quickly dissipating. As expected, there was unanimous support for a Tilden-Johnson ticket, but the party started to divide on the issue of the platform. Vallandigham’s initial draft went too far, for it still recommended an armistice first before negotiations, while, based on the victory at Atlanta, the other delegates wanted the Confederates to surrender and then it would be time for negotiations on the basis of the Union. William Cassidy wrote in dismay that deciding on a platform “involved a fight and probable rupture,” while other delegates denounced that adopting Vallandigham’s plank unchanged would be to take up “the standard of our enemies.”

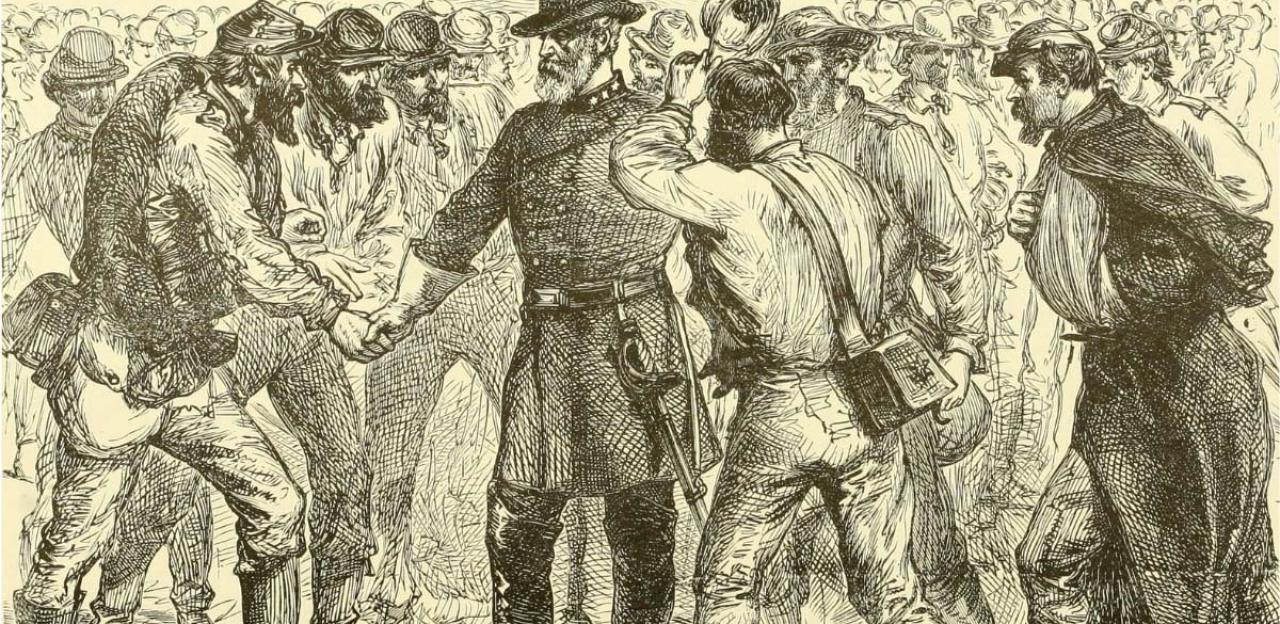

The Second Chicago Convention

When news arrived that Mobile too had fallen, Johnson and his supporters demanded to immediately expel all Peace men, and when Tilden vacillated, they withdrew from the Convention. Outside, Johnson went in a bitter tirade, characterizing the Copperheads as “sympathizers with the rebellion . . . in words and deeds they are the most dastardly cowards the world ever knew.” Johnson’s withdrawal meant that the only people in the Convention were Vallandigham’s Copperheads and the Tildenites. Although there was a mighty effort to at least conclude the fusion between these two factions, Weed now frankly told Tilden that he would abandon him if he negotiated solely with the Copperheads. With no other option, Tilden also withdrew. Further efforts to negotiate a Tilden-Johnson ticket would fail as well, for Johnson accused Tilden of being too close to Vallandigham while Tilden was loath to ally with some of the most extreme elements in the Johnson tent, afraid of alienating moderates even more.

The events thus decided at last that three different opposition tickets would go up against Lincoln that November. This was, needless to say, joyous for Lincoln, who was only regaining strength and confidence, something that also allowed him to patch over divisions within the Republican Party. Some Radicals had remained disgruntled with Lincoln, including the Greeley ring which believed “that it was useless and inexpedient to attempt to run Mr. Lincoln.” Part of their disenchantment was over the continued issue of Reconstruction, with Lincoln advocating for Congress to recognize his governments and in exchange they would ratify the 13th amendment. The Radicals wanted ratification as one among many preconditions instead. In a speech to the Anti-Slavery Society, both Wendell Philipps and Frederick Douglass “with unusual warmth of manner” warned that admitting Louisiana would set a dangerous precedent, allowing all other rebel states to return with similar laws and then “we should have slavery back again, in spirit if not in form.” At the very least, they should be required to adopt universal suffrage, land reform, and equal rights first before being admitted.

This Radical anger had inspired new efforts to try and replace Lincoln, especially as disappointment mounted over the summer’s bloody failures. But the half-formed conspiracy just completely collapsed following Atlanta. The responses of Northern Governors to the letters of some Radicals show this: Governor Andrew declared that “Massachusetts will . . . support Mr. Lincoln so long as he remains the candidate;” while the governor of Wisconsin believed that “the interests of the Union party, the honor of the nation and the good of mankind, demand that Mr Lincoln should be sustained and re-elected.” Soon, all malcontents returned to the fold, and even such embittered radicals as Wade, Chase, and Greeley were stumping for Lincoln. The New York Herald chortled that these “sorehead republicans . . . ultra radical, ultra shoddy and ultra nigger soreheads” were now “skedaddling for the Lincoln train and selling out at the best terms they can . . . crowing, and blowing, and vowing . . . that he, and he alone, is the hope of the nation.” While stumping the West in an effort to regain Lincoln’s favor, Chase conversed with a man “who thought Lincoln very wise,” for if he were “more radical he would have offended conservatives – if more conservative the radicals.” Chase asked himself, “will this be the judgement of history?”

Lincoln had to also soothe the conservatives, some of whom remained unhappy with the amendment and could be seduced by Tilden. The President sent Nicolay to New York, in the “very delicate, disagreeable and arduous duty” to conciliate the Conservatives, according to Nicolay himself. To allay Weed and coax him back into the Republican fold, Lincoln finally granted him control over the Custom’s House, but based on the implicit condition that he would aid Lincoln. Disillusioned with Tilden and afraid of the prospect of losing all his patronage, Weed turned coat and publicly denounced Tilden as Vallandigham’s cat-paw. Soon, Weed’s intimate Simeon Draper, the newly appointed Collector who was replacing a Chase crony, announced he would “hold every body responsible for Mr Lincoln’s reelection and I will countenance nothing else.” The New York Herald noted “the change which has taken place in the political sentiments of some of these gentlemen within the last forty-eight hours—in fact, an anti-Lincoln man could not be found in any of the departments yesterday.” Lincoln thus had expertly played the Greeley-Weed feud, getting both factions to support him openly if not cheerfully, all in the hopes of obtaining his favor and patronage.

Lincoln campaign poster

No wonder then, that after these successes, Lincoln was happier and more optimistic than he had been in months. He further took heart from the obvious divisions that the weeks after Atlanta revealed in the Confederacy, believing these were all signs that the end was near. He even joked that the idea of recruiting Black soldiers was his government’s property and as such “I will have no option but to present a complaint of patent infringement.” Rumors of peace, however, troubled Lincoln somewhat, for he feared that an open offer to end the war could revitalize the Copperheads and maybe spurn them into trying a fusion ticket again. Nonetheless, Lincoln felt he had to show the Northern people that the only ones standing in the way of peace were the Southerners themselves, that being why he planned on accepting Breckinridge’s offer for a peace conference. But at least Speed feared that the Northern people would be “seduced by Breckinridge,” and there were some worries within the Cabinet about what to do if Breckinridge just directly offered Union but not emancipation.

The news of Lee’s death and the coup against Breckinridge consequently stunned the Union government, completely changing its political calculus. Lee’s demise, and later Breckinridge’s execution provoked spontaneous celebrations in many Northern communities, but Lincoln found no real joy in it. With characteristic lack of emotiveness, Lincoln merely observed that “I was fond of John, and regret that he sided with the South.” Grant, too, went as far as prohibiting his men from celebrating. “I would not distress these people,” Grant explained. “They are feeling the fall of their leader bitterly, and you would not add to it by witnessing their despair, would you?” In time, the Union would self-righteously insist that they drew no elation from Lee’s demise, but in truth many celebrated, especially because they believed that “without their Hannibal, the rebels will soon fall defeated and humbled at our feet,” as an editorial stated confidently. Several soldiers claimed to be the ones that shot Lee and many rifles said to be the ones that fired the bullet were sold as souvenirs throughout the North.

The coup confirmed for Lincoln his long-held idea that the Confederacy was in essence a military dictatorship, with the Army of Northern Virginia being Breckinridge’s “only hope, not only against us, but against his own people.” Now, “he has lost control and the armies reveal their true masters . . . they will break to pieces if we only stand firm now,” and as soon as Southerners were returned to liberty they “would be ready to swing back to their old bearings.” This fit well with the Northern conception of the war as one started by wealthy planters who, through terror and despotism, forced the “deluded masses” to betray the Union. The Union, Harpers’ Weekly editorialized, was fighting to overthrow the “terrorism under which the people of the rebellious States have long suffered” by the hands of the planter aristocracy. “We are fighting for them . . . for their social and political salvation, and our victory is their deliverance. . . . It is not against the people of those States, it is against the leaders and the system . . . that this holy war is waged.” Likewise, the New York Times proclaimed that “The people of the South are regarded as our brethren, deluded, deceived, betrayed, plundered . . . forced into treason . . . by bold bad men.”

Now the “bold bad men” had taken over, revealing at last the true masters and objectives of the rebellion. In this way, the coup probably did more to unite and revitalize the Yankees, for it imbued in them the idea that they were liberators, not only of the Black slaves but of the White deluded masses. Invoking “the terrible sufferings of the Union men of the South,” Harpers’ Weekly warned Northerners that to negotiate for peace with the Junta would be to abandon their brethren to “wholesale slaughter and merciless despotism.” More than ever, it was time to sound the call of amnesty for the poor. “May its clarion tones sound loud and clear through all the South, calling off the guilty and deluded masses from their hopeless struggle,” declared General James H. Lane, while a newspaper called on the Federal Army to “break the spell of terror under which Robert Toombs has put our wayward brothers,” and start a Reconstruction that would see poor Whites “raised by education and social influence to their true position in society.” But “the minority of traitors whose guilty ambition brought and continue all the horrors of war,” neither deserved nor would get a pardon, but should be dealt “with stern justice . . . their boasted strength and power swept away, like mist before the rising sun.”

A probe against the rebel lines at Petersburg was supposed to be the first of these final strokes. But the quick execution of the coup and the support it found in the soldiers meant that, much to Grant’s disappointment, the rebel position hadn’t been weakened. Their trenches held up and Grant called off the assault, deciding that he could not completely destroy them just yet. It’s been suggested that Lincoln and Grant followed Napoleon’s adage that one should not interrupt their enemy when they are making a mistake. Winter would come soon, and the Southern Army would just continue to disintegrate, while pushing it out of Richmond would allow it to link up with the Army of Georgia or made them take to the hills, with the Army of the Susquehanna unable to pursue. Because he wished to capture all of the Army of Northern Virginia, Grant decided to bid his time. “I have seen your despatch expressing your unwillingness to break your hold where you are,” Lincoln wired in response. “Neither am I willing. Hold on with a bull-dog gripe, and chew & choke, as much as possible.”

The coup reinforced the view of the Union cause as one of deliverance of the poor, White and Black, from the dominion of the slavocracy

But other Union armies jumped into action to deliver the coup de grace and end the rebellion once and for all. An offensive was planned in the Shenandoah Valley, basically stripped of all troops to reinforce the Richmond-Petersburg line, while a renewed effort would be made to take Charleston. The most important thrust would come from the South, where Sherman was preparing to cut loose and march through Georgia. “This is the time to strike . . . I’ll move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea,” the General said, proposing a campaign to utterly destroy the remaining resources of the Confederacy. But more importantly, he wanted to destroy their defiance and break their spirit. “If we can march a well-appointed army right through their territory, it is a demonstration to the world, foreign and domestic, that we have a power which Breckinridge couldn’t resist and which Toombs cannot resist now,” Sherman proclaimed. “I can make the march, and make Georgia howl!” The Junta that had overthrown Breckinridge to continue the fight until the bitter end would now have to prove whether it could indeed rally the people to victory, or if Breckinridge was right and their efforts could only end in complete perdition.

The Confederate Counterrevolutionaries thus could claim that they were not abandoning the values of 1776 but saving them. Faced with defeat, they felt they truly had no option but to depose their own leader and engage in a last-ditch effort to save slavery, White supremacy, and aristocratic rule from the Union’s frightening emancipation, equality, and a democratic government that included Black men. A soldier so informed his fiancée, saying he supported the coup because he wanted them to live under “a free white man's government instead of living under a black republican government,” while an Alabamian, at the same time as he invoked Washington’s “example in bursting the bonds of tyranny,” boldly said they had to “fight forever, rather than submit to freeing negroes among us.” Such a fate would be rendered even more terrible if it was the result of ignominious surrender. Breckinridge had to be overthrown, the Charleston Mercury justified, because he sought to transform the South into “a mongrel, half-nigger, half white-man, universal freedom, beggarly Republic not surpassed even by Hayti.”

Some went even farther, most notably George Fitzhugh, who denounced the “pompous inanities” of the Declaration of Independence as the work of “charlatanic, half-learned, pedantic authors,” who believed the “infidel doctrine” that “all men are created equal.” Frankly categorizing the Southern Counterrevolution as “reactionary and conservative,” Fitzhugh advocated for rolling back “the excesses of the Reformation . . . the doctrines of natural liberty, human equality and the social contract.” The Gholson report that so bitterly denounced Black recruitment similarly directly warned that a “Democratic Republic without the balance wheel, which our disfranchised laboring class affords must soon degenerate as the experience of the Northern states has proved, into a Mobocratic despotism.” Even fiery nationalists like the writer Augusta Jane Evans confessed being “pained and astonished” at “how many are now willing to glide unhesitantly into a dictatorship, a military despotism.” Pushed to choose, committed Confederates preferred dictatorship to affording Black people liberty and rights.

This is not to say that the coup enjoyed unanimous acceptance from all Southerners. But in the Army, where the ardor for the cause was most pronounced, the new government received initial wide support. Chiefly, there was the fact that they didn’t feel themselves defeated yet, and believed that to surrender would be a stab in the back that would render all previous sacrifices meaningless. “We should yield all to our country now. It is bigger than any singular despot,” exclaimed a North Carolinian. “We must triumph or perish.” A soldier expressed likewise that he preferred to “die fighting for my country and my rights,” rather than in “dishonorable surrender.” And, having seen “the hireling horde” slay so many “who are striking for their liberties, homes, firesides, wives and children,” a Virginian resolved that they would never allow “the chivalrous Volunteer State to pass under Lincoln rule,” as “the traitor Breckinridge wanted.”

George Fitzhugh

Just before the arrival of a regiment under Jackson, Longstreet and a small party escaped to Federal lines and surrendered to Grant, while most of the soldiers in Peterburg cheered Jackson’s arrival and “called for the blood of the traitor Longstreet, who was going to betray General Lee by surrendering our city to the abolitionists,” reported an officer. This reveals another reason for supporting the coup – the belief that doing so would best preserve and honor Lee’s memory. Junta supporters again and again emphasized the “indomitable valor” of Lee, insisted that the late General “would never contemplate or allow the abashment and disgrace of surrender,” and posited that Lee himself would have overthrown Breckinridge had he lived. History has been unable to agree on interpreting Lee’s actions, his loyalty to Breckinridge and general pessimism in the last months clashing with a sense of duty and certain refusal to accept defeat. But at the time, among the soldiers the general conviction was that Lee would have wanted them to continue fighting. “I am doing this for Marse Lee and Virginia, not for that dammed Toombs,” explained a private to his sister.

Longstreet’s decision to flee would soon prove wise, as shown by the unhappy fate of General Cleburne. Appointed to lead a united “Army of Georgia” following the disaster at Atlanta, Cleburne was arrested by his own troops, who now derided him as the “architect of Breckinridge’s Negro policy.” Cleburne tried to resist the arrest, and rally men to his defense, but they shouted him down, calling him a “Nigger lover.” While trying to escape, Cleburne was shot and killed. A few days later, Johnston returned, having regained command of the Army as a reward for his role in the coup. He announced that “the traitors in the government that betrayed you” had been removed, and now “we the patriotic men of the South are ready to abandon their ruinous policies and lead you to a final triumph.” Loud cheers for Johnston, and for Toombs and Jackson, followed the proclamation. And those who doubted were unable to raise their voices over this fervent, desperate delusion.

Some have blamed the coup’s success on the supposed cowardice of men like Longstreet, who preferred flight to fight. Asked why he didn’t stand by Lee after the war, Longstreet replied icily that “General Lee was dead.” Longstreet maintained to his dying breath that Lee would have never betrayed Breckinridge, and that a countercoup could only “unleash the evils of fratricide within the Southern armies.” This was shown by the Orphan Brigade, which conspired to try and stage a mutiny to free Breckinridge. Their efforts floundered, mostly because Breckinridge himself opposed any kind of revolt. Instead, many ended up deserting, and it is said that when the news that Breckinridge would be trialed were announced many men threw down their arms on the spot. The fears that the Brigade or other regiments would act justified for the Junta the decision to execute Breckinridge. Similar fears motivated the start of a purge of “Breckinridgites” in the Army and government.

Some allies of Breckinridge, including many of the advocates of Black recruitment and the staff of the de facto administration organ the Richmond Sentinel, were arrested the same day as the former President. Within the former Cabinet, only Campbell was executed, while trying to flee, while the rest was sent to military prisons – the Junta being actually gracious enough to place the sickly George A. Trenholm under house arrest. But perhaps the greatest show of the Junta’s new direction was the events in Congress. Meeting under the watchful eye of Jackson’s soldiers, the remnants of the Congress were barely able to muster up a quorum, for several Nationalist legislators had been arrested and others fled. A bill was immediately proposed to recognize the Provisional Government. Senator Wigfall stood up then. While he denounced Breckinridge’s “tyranny & reckless disregard of law and contemptuous treatment of Congress,” Wigfall insisted that there was no legal basis for a Provisional Government. Even if “the urgency justifies setting aside the forms of law,” the proper course was for Stephens to assume the Presidency.

Pushed to choose between their President and what they believed to be their General's legacy, the soldiers chose Lee

Stephens himself would raise that point shortly. He furthermore opposed the formation of the ad hoc tribunal that tried Breckinridge and Davis, proposing they be judged by ordinary Virginia courts instead, and was the only member of the Junta to openly speak against their execution – though mostly on the basis that the Confederate government had no legal authority to execute any civilian. Wigfall’s and Stephens’ arguments threatened the security of the Junta, and Wigfall would soon be arrested while a disillusioned Stephens would leave Richmond less than a month after the coup. Soon, a Congress without quorum voted on the resolution granting post facto legitimacy to the Junta and then voted to adjourn. The Confederate Congress would never meet again. From his home in Georgia, Stephens denounced the Junta as a “Mexicanization” of politics that “has shown itself to be an even worse tyranny.” But whereas Breckinridge’s “despotism” was always denounced openly, Stephens prudently said nothing publicly, staying home until Union forces arrested him after the end. “Toombs is now dictator,” Stephens wrote sadly in his last day in Richmond, “and all hopes are gone.”

Not all Confederate politicians and soldiers were willing to back the coup, however. General Kirby Smith, the practical commander in-chief of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi, denounced the coup as an act of “usurpation” and refused to follow its orders, releasing a proclamation where he declared Stephens the legitimate President and said he would only obey orders from Congress. After Breckinridge’s execution and the dissolution of Congress it dawned on Smith that that there was little hope of a countercoup, and that Stephens was completely uninterested in opposing the Junta. Accordingly, Smith declared he would act independently of Richmond and in coordination with the almost defunct State governments in his department, until the Congress reconvened or a new one was elected. For all intents and purposed, Smith had become a warlord.

Smith’s decision was not so much based on personal loyalty to Breckinridge. In fact, Smith was something of a dead-ender too. Rather, it was based on an opposition to the leaders of the Junta as a “band of rascals and failures,” and the realization that the coup had gutted the legitimacy of the government. A similar reasoning led General Taylor and the Native American General Stand Watie to pledge the loyalty of their remaining forces to Smith rather than Toombs. Far different was the reaction of John Singleton Mosby, who was genuinely loyal to Breckinridge and surrendered himself, alongside around a third of his partisan force, to Grant, claiming there was “no government we owe allegiance to anymore.” For their part, the forces under Sterling Price in Missouri and Kansas, and those under Forrest in Tennessee and Northern Mississippi, all also refused to heed the Junta, but did not pledge loyalty to anyone else either. Thus, all these commanders became in essence guerrilla bands, and have been labelled as the “Confederate warlords.”

A furious Toombs threatened to have Smith and all who followed him trialed as traitors, but he was conscious of the fact that the effective power of his new government did not extend much farther than the territory under the control of the Armies of Georgia and Northern Virginia. However, the Junta still repressed dissent harshly, closing critical newspapers and executing scores of soldiers who wanted to desert, including the last remnants of the Orphan Brigade. Such events allowed the opponents of the Junta to talk of a “generalized purge and reign of terror.” In reality, the purge was a rather superficial one. The majority of the bureaucracy and civil officials of the Confederacy retained their posts, and government routine was not greatly disrupted. Even John Jones, an ardent Breckinridgite, was not ever bothered by the new regime, leading him to comment that “the events following the revolution against Mr. Breckinridge have seemed like a most surreal dream.” This answers to the counterrevolutionary nature of the coup, for similarly to secession it was executed mostly to prevent the adoption of measures opposed by the South’s leaders, rather than to adopt new measures themselves.

Another aspect in which the Junta was similar to secession was its quick and decisive execution, meaning that many Southerners were simply confronted by a fair accompli when they first learned of it. Among most planters the reaction was support, even if it sometimes was qualified. On one side Catherine Edmonston cheered the remotion of “our Congress, our public men, our President & his imbecile Cabinet,” for “They it is who have beaten us,” and expressed confidence that “this is the inauguration of a period of victory and rights.” At the other extreme Mary Chesnut condemned the coup as “black treason,” and said she “wept bitterly for our gallant leader. Why is it that the best of us are victims of the worst betrayals?” Chesnut’s opinion, however, was certainly influenced by the fact that her husband had been arrested for having served as an aide to Davis. Nonetheless, the great majority of those who opposed the Junta did not dare say anything. Senator Graham, for example, privately wanted Stephens to assume the Presidency and arrange a peace, albeit one that preserved slavery. Graham thought the coup “an act of treachery and imbecility,” but said nothing publicly.

Richard Taylor

Other members of the planter elite preferred to hide in blissful ignorance, ignoring both the coup and the Yankees. “Never were parties more numerous,” reported an Alabama newspaper. “The love of dress, the display of jewelry and costly attire, the extravagance and folly are greater than ever.” The South Carolinian Grace Elmore believed that this “utter abandonment to the pleasure of the present” was the only way of “shutting out for the moment the horrors that surround us.” With almost tragic insight, Katherine Stone observed that the planter aristocracy lived “the life of the nobility of France during the days of the French Revolution—thrusting all the cares and tragedies of life aside and drinking deep of life’s joys while it lasted.” If the Junta had failed to raise their morale, it hadn’t spurned them to act against it either, for “the situation has not changed, not at all – we are still going down in disastrous defeat,” as one man explained. “So, why should we bother?”

Among many Southerners outside the political and economic elite, the reaction was a mix of initial shock and apathy. As a Federal officer observed later, “it is exceedingly hard for the common people to care who their next leader will be when they must wonder what their next meal will be instead.” The anger and bitterness that would settle in later took some time to materialize. This is owed, again, to the counterrevolutionary nature of the coup – whereas Breckinridge’s decrees had been opening new terrifying possibilities such as Black recruitment and a return to Union rule, the Junta seemed, by contrast, a return to the status quo before Atlanta’s fall. A Georgia community, for example, celebrated when Black slaves pressed into military service were shackled and returned to their slavers. By promising victory without Black recruitment and blaming all that had gone wrong in the previous administration, the Junta revitalized the hopes of many Confederates, who clung to the idea that they could yet seize victory from the rapidly closing jaws of defeat.

“Never before has the war spirit burned so fiercely and steadily,” claimed the Richmond Dispatch, commenting on the supposed uptick of morale. Josiah Gorgas, retained in his post due to his talents, also said that “The war spirit has blazed out afresh.” Only later would the Dispatch admit sullenly that this was nothing but “a spasmodic revival, or short fever of the public mind,” that left among the people only “a dull, helpless expectation, a blank despondency.” But at the time, the Junta insisted that things would soon turn for the better, and gleefully printed reports of men returning to the Armies based on a general amnesty. To try and show the people that the situation was improving, the Junta opened the food stores Breckinridge had been saving for the winter and for food relief and used the Treasury’s dwindling specie to pay some salaries. For those who paid attention, however, the Junta’s real priorities were clear, for far more specie was used in paying slaveholders back for the human chattel Breckinridge had taken.

Initial sanguine expectations proved wildly mistaken, as the Junta failed to raise either more men or material. Some planters, trying to prove Toombs’ argument that the slavocracy would be glad to offer anything if only the government removed its heavy hand, had indeed donated supplies and food to the hungry. But the majority preferred to simply save their property for themselves and for profit. The Junta, too, realized that its most ultra demands such as an end to the draft and impressment were simply unpracticable, and while assurances flowed from Richmond that those policies would soon end the government just continued them. Even worse, they sought to “equalize” the burden by requiring the poor people to contribute as much as the planters, whereas Breckinridge had always tried to impress more from the rich.

Especially during the winter, poor Confederates started to feel the effects of the Junta’s pro-planter policies. Breckinridge’s food relief corps had never been able to completely stave off hunger, but the program was completely abandoned after the coup, bringing entire towns perilously close to starvation. The revocation of Breckinridge’s decrees had, furthermore, freed food and supplies that had been taken from planters with the purpose of feeding the common folk, allowing them to sell these goods at inflated prices instead. Some communities would even remember landowners burning food crops Breckinridge had forced them to plant, naturally after reserving a portion for themselves, all so they would have more land for cotton or other more profitable crops. “The sight of the burning green maize and potatoes caused a ripple of despair in all of us,” a man remembered after the war. “In that bonfire our last hope was turned to ash . . . It was the same as if they had burnt our children alive.”

The actions of the Junta only worsened the food situation in the South