President Abe Czar Alexander loved

"Mankind's delight", nor were his hopes reproved

Both sovereign potentes, both despots too

Each with a great rebellion to subdue

Alike prepared to sing and to reply

The precious pair thus bragged alternately

Abe: Imperial son of Nicholas the Great

We air in the same fix I calculate

You with your Poles, with Southern rebels I,

Who spurn my rule and my revenge defy

Alex: Vengeance is mine, old man; see where it falls,

Behold yon hearths laid waste, and ruined walls,

Yon gibbets, where the struggling patriot hangs,

Whilst my brave myrmidons enjoy his pangs

Abe: I'll show you a considerable some

Of devastated hearth and ravaged home;

Nor less about the gallows could I say,

Were hanging not a game both sides would play

- The President and the Czar by Punch Magazine

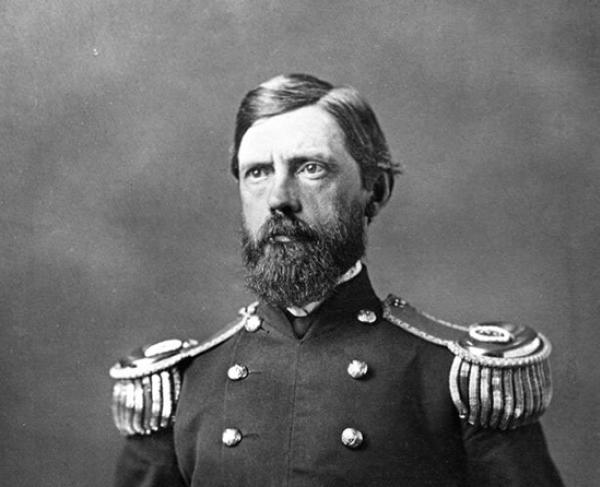

A tall, handsome man in the impeccable uniform of a Union general approached Lincoln’s office in Philadelphia, in February, 1863. The people of the temporary capital paid him no mind. It was not unusual to see Union army commanders, and most people were waiting with bated, anxious breath for news of Hooker’s campaign against Lee. Just a couple of weeks later, news of the Manassas disaster would arrive and cause a moral crisis. This was, of course, distressing news to President Lincoln, but he had always held his reservations about Hooker. This is why he had summoned John Fulton Reynolds, recently exchanged, to enquire whether the Pennsylvanian was willing to take the reins of the Army of the Susquehanna.

The need was pressing. Hooker had proven unequal to the great trust the Republic placed on his shoulders, and now it was clear to everyone that the aggressive Lee was preparing to invade the North. The Union cause seemed to be almost finished, all that was needed was another rebel victory. Whether the Confederacy and slavery or Union and liberty was to triumph was to be decided in this campaign. Lincoln decided that Reynolds was the man for the job. Tall and elegant, with dark eyes and a trimmed beard, the West Pointer veteran who had been with the Army since the Mexican War was regarded as a charismatic, brave and capable officer. Loved by both troops who cheered him openly and comrades who described him as the “noblest . . . bravest gentleman in the army”, Reynolds seemed the very picture of martial excellence and republican nobility.

Naturally, this picture of a perfect man is not completely true. Reynolds had neither political connections nor friends in the press. He was an apolitical man who regarded politics as distraction from more important business. He regarded his objectives as merely the preservation of the Union and the defeat of the Confederacy, instead of the revolution the Republicans were starting to envision. Reynolds’ background as a conservative Democrat whose entry into West Point was sponsored by none other than James Buchanan informed these views. He had grown somewhat disillusioned with both political parties, and never quite became a Chesnut, instead doubling down on his belief that the military should be an apolitical institution. He never expressed McClellan’s insubordination or Sherman’s exaggerated contempt for politicians, but neither did he grasp, like Grant did, that at that level military affairs were inherently political. The Union Army was as much an extension of the Lincoln administration’s ideology and policies as the Confederate Army that of Breckinridge’s.

Furthermore, Reynolds had never held an independent command, and though he fought gallantly in Anacostia and the Peninsula, he had a worrying tendency towards micromanagement. Certainly, it was not adequate for an officer of his rank to go and personally direct the artillery. After the defeat at Mechanicsville, Reynolds was ascended to commander of the 1st Corps, or what remained of them anyway, and once again he showed extreme bravery that was not enough to turn the tide. No matter, it’s doubtful that anyone could have created a victory from such a desperate situation, but Reynolds would be captured and spend some months in a Richmond prison before being exchanged. Legend has it that he was captured while riding along the line cheering his troops valiantly, the Union flag wrapped around his shoulders. He was exchanged too late to take part in the Battle of Bull Run, and he endeavored to raise new volunteer regiments when he was called to Philadelphia.

The General was not squeamish about the hardships of war. During the Peninsula, he had expulsed men based only on suspicions that they were secesh. But for Reynolds all these decisions had to respond to military need, and ideology, politics, and the squabbling of Philadelphia bureaucrats had to be left aside. Lincoln, naturally, had to take into account Reynolds’ political leanings. But his main concern was just winning the war. The question of Reconstruction could be decided later; the important duty was to whip the rebels. That’s why he decided to take a chance on Reynolds. No general, the President realized, matched his bravery and aggressiveness, and in the aftermath of two terrible defeats someone who was loved by the troops and respected and trusted by the officers would be needed. Thus, Reynolds, the “soldier general of the Army”, was offered command of the principal Union Army in the East.

Despite having his own ambitions and being honored by the confidence Lincoln expressed, Reynolds hesitated. He asked whether he would have “absolute control” of his movements, and reportedly said that if he could not, then he would refuse command and it would be better to entrust it to George Gordon Meade, a personal friend. Lincoln answered that in matters of general strategy, he was to be subordinate to his superiors, but that the only tactical instruction he was receive is to follow Lee’s army and defeat it. Reynolds still hesitated, possibly afraid of getting involved in political matters. Then Lincoln, with his sorrowful eyes and deep lines that betrayed the toll of that cruel war, leaned forward. “I have always wanted a General that would not intervene with the business of government, but that would lead the army gallantly and justly,” the President said, “a General that will only do his duty as a soldier.” Reynolds nodded, and answered with equal seriousness: “I shall do my duty, sir.”

The accuracy of these reports has been challenged. They come from Reynolds’ brief letters, and comments made after the fact by his peers. Lincoln did not make any comment about that fateful reunion, except to praise Reynolds. If a deal between the two men was truly struck, it apparently was not fulfilled, because there are signs that point to further meddling by Lincoln. The reasons why Reynolds decided to accept the command are somewhat murky. There’s the fact that General Meade had been injured in the Battle of Bull Run, being thrown off from his horse and receiving a serious concussion. Meade was still fit to command, but he insisted nonetheless that if Reynolds was offered command, he should take it. “No man is more respected than you, and it would be our greatest pleasure to follow you gallantly in defense of our Union”, Meade wrote. Finally, it’s been suggested that Reynolds felt shame for not taking part in the Battle of Bull Run, and felt that his native Pennsylvania was to become a battlefield thanks to his own shortcomings. To right these errors, he decided to accept Lincoln’s offer. Whatever the exact motivations, John F. Reynolds took command of the Army of the Susquehanna in March, 1863.

There was reason to be afraid of rebel invasion. The Confederates, enjoying their high tide, had growth bolder in their attacks and demands. In turn, the war stopped being a conflict between gentlemen, and outbursts of violence and guerrilla warfare resulted in a bloody tic-for-tac of attacks and reprisals that covered the United States with blood. Atrocities started to take place with alarming regularity, as Northerners and Southerners both grew dogmatic in their demands for unconditional loyalty. Everybody that opposed the war was denounced as a traitor or a Tory, depending on the section. Instead of being merely shunned or arrested, they would be dealt with as an enemy, a hostile group to be chased and exterminated. And so it was that after 1863 Union commanders started a scorched-earth campaign that devasted large sections of the South, hanging partisans without trial and exiling Confederate sympathizers; while Confederate guerrillas murdered Unionists and African Americans, and started a series of raids into Union territory with deadly consequences. After 1863, there was no going back, no possibility of peace, until one side or the other was completely defeated.

The first signs of this ruthless kind of warfare had been already observed in Missouri and Kansas. Affected by the bitter legacy of Bleeding Kansas and the Lecompton debacle, Kansans and Missourians hated each other with “more vehemence and abhorrence than even the Greek and the Turk”. Forced to live under a government they regarded as inherently illegitimate, Kansas Free-Soilers had been pursued by both legal and extralegal means for many years. Lecompton law had allowed for the trial and execution of anyone who criticized slavery or helped slaves escape. In many occasions, men were pursued by Border Ruffians deputized by corrupt authorities, receiving corporal punishment, having their lands confiscated and being outright murdered. In turn, these Jayhawkers, unable to appeal to either the law or a Federal government led by the doughface Buchanan, resorted to violence.

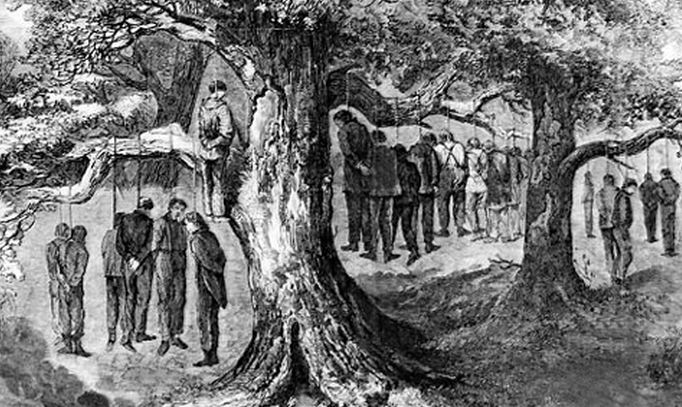

Mass executions of rebel sympathizers in Union territory and Unionists in Confederate territory were starting to happen

Bleeding Kansas thus continued beyond the Lecompton vote, but it was somewhat quieted down by the presence of Federal troops. But the war meant that vengeful Jayhawkers were not simple terrorists but soldiers of the Republic, and Border Ruffians were not petty tyrants but the gallant resistance against Lincolnite oppression. Thus, both groups were legitimized as parts of their countries’ war effort, but neither Lincoln in Philadelphia nor Breckinridge in Richmond had much control over their actions or their methods. This explains the unusual level of violence, fed not so much by patriotic allegiance or the ideological objectives of each combatant, but as a way to settle old scores and vent violent urges. Missouri and Kansas thus became bloody battlegrounds from the start of the war, embroiled in a cycle of slaughter that would eclipse even the worst acts of Bleeding Kansas.

At first, the struggle continued under the guise of Victorian “civilized warfare”. General Hunter, for sure, took radical measures in using emancipated slaves to fight the rebels and the new Kansas government also passed laws for confiscation and punishment. But under this guise of moderation, alarmed Northerners already saw that the Kansans endeavored to not just hurl the traitor crew from their government, but enact bloody vengeance upon them. Murderers and loiters who had gone unpunished during the Lecompton period were hanged, and the Kansas forces were the first to deal with partisans through the measures of hard war, that is, scaffolds and exiles. But by and large, the Confederate and Union armies still observed the rules of war and neither pushed the war to its natural but terrible consequences. That changed after the Emancipation Proclamation, when rebels, now convinced that Union victory would mean their destruction, struck with more brutality, resulting in equally abominable reprisals.

The cycle of violence was started when a man named Andrew Allsman, a Free-Soil veteran of Bleeding Kansas, was taken prisoner and executed by rebel partisans who resented how Allsman led Union troops through Missouri terrain. The Emancipation Proclamation had already been issued, and thus some of the troops led by Allsman were Black recruits, who took part in a raid where lack of discipline resulted in wanton looting. Border Ruffians, completely terrified of the idea of Black Union soldiers sacking and burning houses, decided to make an example of Allsman, to show that “all white men have to side with their own race against Lincoln’s negro murderers.” Allsman was kidnapped by a guerrilla band, his head was cut off and then placed in a pike in the middle of the town of Palmyra, a message written down: “Warning! All abolitionists who seek to start a domestic rebellion or attack the people of Missouri shall receive the same fate.”

Allsman’s execution shocked the nation. Southern Patriots had routinely inflicted such cruelty in escaped slaves during the Revolution, but Allsman was a white man engaged in “civilized warfare”. Even many Southerners were appalled by the events, but they accepted it after wildly exaggerated rumors of Black troops burning houses and raping women started appearing in the news. The Federal commander in the area, one John McNeil, decided to strike back with ruthless fury. A few weeks after Allsman’s head appeared in Palmyra, he captured 10 Confederate partisans. He executed them immediately and then announced that for every Unionist murdered by partisans from then on, he would execute one prisoner. For good measure, he declared that the murder of Black Unionists would also result in an execution. In Philadelphia, though Lincoln paled at the prospect of such bloody vengeance, he somberly approved the measure, saying that they could not allow those marauders to believe that they could execute Union men with impunity.

McNeill’s actions caused revulsion among some Northern and European newspapers at first. The British magazine Punch even compared Lincoln with Tsar Alexander of Russia, then engaged in a campaign to subjugate Polish rebels. But the squeamish Northerners were soon filled with a spirit of terrible vengeance when news of more rebel atrocities arrived. Breckinridge immediately demanded that McNeill should be tried by the Federals, and if they declined to do so, then he should be surrendered to Confederate authorities. The Union, naturally, refused. Breckinridge was going to left the matter at that, but local authorities took a version of justice on their own hands and executed 10 Unionists. Horrified Londoners quickly denounced these acts, saying that “If a National General in Missouri shoots ten prisoners for one man killed, why should not a Confederate General shoot a hundred prisoners . . . for these were known to be killed; and so on until all prisoners on both sides are butchered in cold blood as soon as taken!”

Extremes Meet, or The President and the Czar by Punch Magazine

Mark E. Neely says that “Enthusiasm for retaliation among high-ranking military and political leaders almost always ebbed with the passage of time”, but in the case of the bush war in Missouri and Kansas, atrocities followed each other with such dizzying speed that the thirst for revenge was never truly quenched. McNeill himself said that he would “refer to God for the Justice of the act”, and confessed to further war crimes: “The morning after the battle of Kirkmill, I shot fifteen violators of parole—the next day an officer was tried & shot for being a spy & a Garilla subsequently at Macon City Genl Merrill shot ten men for the same cause.” But McNeill was never tried, and he was even promoted after a campaign by hundreds of Missouri Unionists who saw him as their protector. Missouri troops, after the lamentable events of Palmyra, went forward into battle shouting “Hurrah! Now for McNeill!” The gory precedent of executions as retaliation for crimes continued, and soon enough “northeastern Missouri was left barren of life, all men either in swamps or under the sod, both armies fighting under black flag.”

It’s possible that the situation would ultimately return to normal had it not been for the activities of guerrillas. Neither McNeill nor the Confederate commanders ever executed as many men as they could, but guerrillas had no such qualms. Hungry for weapons and food, Confederate guerrillas “scouted” the countryside, stealing everything they could and abusing Unionist civilians, even to the point of reenacting Allsman’s murder. Reports of many cities in Missouri and Kansas were head in pikes with warnings to abolitionists appeared. Moreover, the marauders took special pleasure in ambushing and murdering Black Union troops and contrabands of war, “leaving the corpses so disfigured that it’s impossible to even determine the sex of the victim.” Yankee commanders retaliated by taking civilians prisoner in Federal camps and putting Confederate prisoners to hard work, so that rebel attacks would result in casualties among their own. But this was not enough, and soon enough Union partisans started to copy the methods of their rivals.

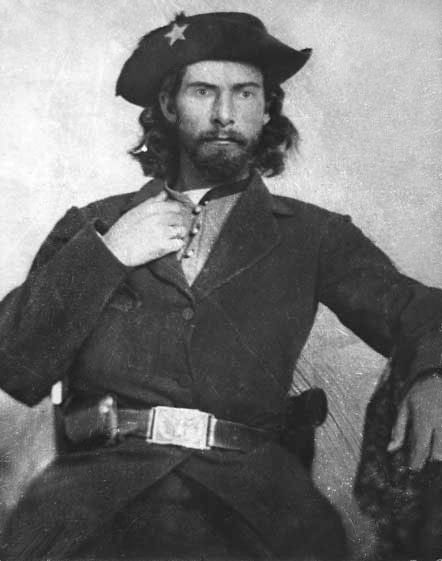

The most famous partisan was Bloody Bill Anderson, a man who had split off from another raider, William Quantrill. Leading a band of “pathological killers like their leader”, Bloody Bill and his men sowed terror and devastation through Kansas and Missouri, murdering and even scalping Unionists and unarmed Northern soldiers. In Centralia, in late 1862, Anderson destroyed a train, murdered unarmed Union soldiers in furlough, and then “Chased out of town by three companies of militia, the guerrillas picked up 175 allies from other bands, turned on their pursuers, and slaughtered 124 of the 147 men, including the wounded, whom they shot in the head.” William Quantrill, not to be outdone by his pupil, committed an even greater atrocity in Lawrence, the old center of Kansas Free-Soilism. Ordered to “Kill every male and burn every house”, Quantrill’s raiders massacred “182 men and boys and burned 185 buildings in Lawrence.”

The Union response, by both the Army and partisans, was swift and ruthless. David Hunter, John McNeill and Thomas Ewing started a manhunt that saw hundreds of partisans captured and immediately shot or hung. More than 10,000 Missourians were banished from the border areas, “leaving these counties a wasteland for years”. Guerrilla bands such as the 7th Kansas Cavalry, also known as Jennison’s Jayhawkers, “plundered and killed their way across western Missouri”, resolved to “exterminate rebellion and slaveholders in the most literal manner possible.” This particular guerrilla group included none other than John Brown Jr., and it’s said to have gone into battle singing “We’ll hang each damn reb from a sour apple tree!” “Jayhawking Kansans and bushwhacking Missourians took no prisoners, killed in cold blood, plundered and pillaged and burned (but almost never raped) without stint”, says James McPherson, and this last point has even been questioned by historians like Kim Murphy.

A Southern man described the scenes of massacre in the Missouri-Kansas border: “The disorder in this army was terrific . . . It would take a volume to describe the acts of outrage; neither station, age nor sex was any protection; Southern men and women were as little spared as Unionists; civilians of every allegiance were put to the knife or had their hearts pierced.” Both partisans and regulars kidnapped free Blacks and forced youths into service, which “gave to the army the appearance of a Calmuck [Mongol] horde.” Neely also says that “Scalps dangled from saddles and bridles. Confederate marauding was commonplace and plundering unstoppable”. The cooperation between Confederate regulars and partisans and the tacit acceptance of Richmond gave the appearance of such depravity being official rebel policy, which horrified the Yankees even more. Indeed, Sterling Price officially congratulated Anderson and Quantrill received a commission as a captain, which further outraged the North.

This in turn augmented their resolve not to surrender. After all, Southern newspapers were saying that they would not accept peace unless “Maryland, Missouri, Kentucky, Kansas and other territories and provinces that by right belong to the Southern people . . . are surrendered at once to us.” Declarations by both Lee and Breckinridge of how they would go onto “liberate” those states raised concerns of the Union men there being subjected to the same kind of cruelty. “We should not, we must not, we cannot abandon our compatriots to that fate”, insisted Northern editorials, and war meetings said that the war could not stop “until every single Southern marauders is brought to justice . . . To dishonorably surrender now would be to condemn our own people to a

barbarian treatment.” Indeed, “barbarian”, “mongol”, “Indian”, were adjectives frequently used to describe the Southern army and the atrocities they committed.

Reports by the Committee on the Conduct of War helped along to expose Southern “barbarism”. Unfortunately, an element of prejudice played a part, for one of the things that most horrified the Northerners was the use of Indian troops by the Confederates. In the Battle of Pea Ridge, Indian regiments allied with the Confederates scalped and murdered prisoners of an Iowa company. General Curtis reported that “many of the Federal dead . . . were tomahawked, scalped, and their bodies shamefully mangled.” The Confederate authorities there answered that if Lincoln had no problem with “negroes murdering their masters in their sleep” then Breckinridge should have no problem “using savage Indians to scalp abolitionists”. “The employment of Indians involves a probability of savage ferocity which is not to be regarded as the exception but the rule. Bloody conflicts seem to inspire their ancient barbarities, nor can we expect civilized warfare from savage foes”, Curtis, who started to use Indian troops too, insisted.

The terrible atrocities of the Kansas-Missouri area were at first dismissed as the natural result of employing Indians in a war between “civilized belligerents”. But Confederate atrocities in Mississippi and Tennessee certainly proved that the White man could be just as savage. The dreadful actions of Forrest and his partisans, who murdered Unionists and terrorized freedmen, have already been described. It was their bloody campaign that led Grant’s Vicksburg plans to failure. This campaign also featured the first large-scale appearance of a dreadful crime that would become horribly common: the wholesale massacre of Black troops. Albert Sydney Johnston did chastise his soldiers for engaging in their base instincts after the victory at Canton, which saw the surrendering First Kansas Infantry massacred almost to the last man. Johnston did nothing, while Breckinridge ordered an investigation – the orders were never carried out, a clerk informing his President that it would be extremely unpopular to prosecute White men for the murder of African Americans.

“To think that the Southern people, who we once regarded as our kind and civilized countrymen, could engage in such crimes”, wrote George Templeton Strong, “fills the soul with disgust and dread.” Massacres of such kind were reported almost weekly, and psychopathic Southerners were able to murder at their hearts’ content. "I assure you it was a great pleasure . . . to go over the field & see so many . . . of the African descent lying mangled & bleeding on the hills around our salt works”, wrote one to his mother after his regiment had massacred a surrendering Black regiment. "We surely slew negroes that day," said a Confederate soldier who was still a boy, having lied about his age. Contraband camps especially drew Southern ire, and thousands of Union troops had to be placed to protect them from raiders who frequently appeared to enslave freedmen, murdering those who refused to go.

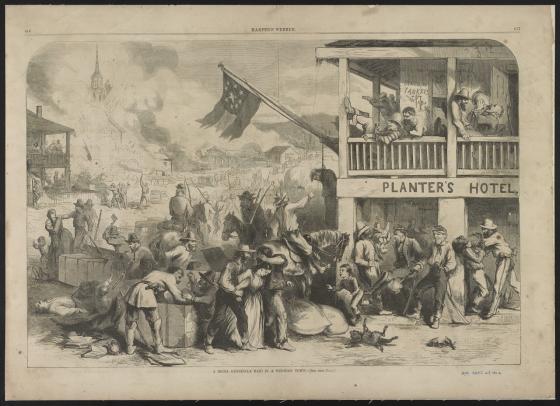

Northerners also felt the effects of Southern depravity thanks to daring raids. Following Bragg’s failed Kentucky campaign, guerrillas as brutal as those of Missouri started to appear in the Bluegrass state too. Blaming their Unionist neighbors for Bragg’s failure, Confederate-aligned partisans started a campaign of terror that saw hundreds of Unionists, Black and White alike, murdered in cold blood. The events of Lexington, Knoxville and Chattanooga brought further tragedies – as Thomas’ army approached, panicked Confederates fled the city, including women and children who “would perish for want of food and warm in the blood-stained snow”. In truth, Thomas and his army offered both to Southern civilians, but partisans still blamed the Federals and decided to enact revenge. Several raids into Ohio and Indiana by Kentucky Confederates resulted in the death of many civilians and great destruction of property, and the complete destruction of all least three small towns in fires, after extracting a ransom. Many free Blacks, “estimated and well-loved members of their communities”, were kidnapped and taken South to be slaves.

Southern civilians expulsed by the Union Army

Years ago, the Fugitive Slave Act had caused great furor in the North. It allowed Southern slavers to go into Northern communities. Armed resistance and heart-breaking images of men hauled back to bondage helped along to create an atmosphere of hate against slavery and the South. This was a hundred times worse, for it was free people that were captured. It was even said that children and women were captured and cruelly whipped. The explosive outrage that engulfed the North by these reports cannot be understated, for it imbued many Northern communities with a thirst for revenge. “If we surrender to Southern terror,” a speaker declared, “they will continue these kinds of outrages for the rest of history. They will continue their campaigns of rapine, of murder, of kidnapping, to show us that they are

masters. Our only option is to defeat this rebellion once and for all.”

Thomas and Grant, with heavy hearts, approved hard war measures that were the only way of dealing with these partisans. Confederate sympathizers were expulsed or taken prisoner, including women and children who sheltered them. Whole areas were reduced to barren wasteland due to the exile of thousands of rebel sympathizers. Black regiments were organized and armed to protect their contraband camps from raiders, who would then be hanged without trial, for, as “insurgents with an appalling lack of respect for the rules of civilized warfare”, they did not deserve trials. Grant and Sherman, in special, would soon inaugurate a style of war that had as its objective the complete destruction of Southern resources and their will to fight, showed by the path of destruction that Grant carved in his retreat from Canton, his soldiers looting and destroying everything they could. This kind of warfare would have horrified both South and North in 1861; by 1863, both sides accepted it as the only way of drawing the war to a close.

Northern intransigence was augmented by news from the appalling treatment of White Unionists and prisoners of war in the South. White Unionists, accused of being traitors ironically enough by secessionists, suffered terribly under Confederate rule. The liberation of East Tennessee allowed for an outpouring of sorrowful stories of abuse. Unionists were imprisoned and had their poverty confiscated. If captured in acts of sabotage, they would be hanged or shot without remorse or mercy; after the Union started to take reprisals against Confederate partisans, the South also skipped trials. Unionists communities were devastated by Southern attacks, destruction and confiscation resulting in “the total impoverishment of the sufferers.” After the passing of conscription in the Confederacy, Unionists fled to swamps or woods, and were then pursued with bloodhounds. When captured, if they persisted in their Union sentiments, they would be massacred, as happened to 13 prisoners in North Carolina.

“They were driven from their homes . . . persecuted like wild beasts by the rebel authorities, and hunted down in the mountains; they were hanged on the gallows, shot down and robbed. . . . Perhaps no people on the face of the earth were ever more persecuted than were the loyal people of East Tennessee”, said one of the victims. “We could fill a book with facts of wrongs done to our people...” an Alabama Unionist declared too. “You have no idea of the strength of principle and devotion these people exhibited towards the national government.” Memories of persecution and attacks created bitter memories that would remain through Reconstruction and beyond. Some Unionists, in order to defend themselves, even allied with Black fugitives, possibly agreeing with Parson Brownlow’s declaration that he would arm “every wolf, panther, catamount, and bear in the mountains of America . . . every rattlesnake and crocodile . . . every devil in Hell, and turn them loose upon the Confederacy”. In this case, one Unionist declared vulgarly, “we prefer niggers to rebels.”

Some of the most appalling violence came from men like Colonel Vincent Witcher, nicknamed “Clawhammer”. Taking advantage of the lamentable way that wars tend to legitimize murder and violence, Witcher and his boys rode through Unionists areas of the South, terrorizing anybody that did not show 100% loyalty to the Confederacy. Using methods such as “Witcher’s Parole”, which consisted in tying a man’s neck to a branch, drawing it back, and then letting it go, which decapitated them by tearing their heads away. Witcher’s boys were so extreme that even fellow Confederates denounced them as “thieves and murderers.” But they were officially accepted as the 34th Virginia infantry. This did not stop their campaign of brutality, for they continued to butcher Unionists. At Powell Mountain, one man was so mutilated that he could only be recognized due to the special underwear his mother knitted for him. Tasting victory, Confederates endeavored to destroy all unloyalty to their new country, saying that “any abolitionist sentiment or remaining loyalty to the old Union must be exterminated”.

The guerrillas obeyed no orders from Richmond or Philadelphia, waging their own bloody campaigns without oversight and giving no quarter

This naturally had the opposite effect, as men who wanted to remain neutral were pushed to one side or the other, and in quite a few cases, they chose the Union. “Dem yankees hav never attacked me or my family”, an Appalachian man wrote, “but the men of Richmond have taken my cotton and my son.” “Marauding bands of deserters plundered the farms and workshops of Confederate sympathizers,” says Eric Foner, “driving off livestock and destroying crops . . . and engaging in reprisals against the Confederate authorities.” Indeed, Unionists and their secret organizations engaged in murder whenever they could, forcing Richmond to send armies to upcountry areas. In places where Confederate authority was already weak at the start of the war, it disappeared completely from 1863 on. Not even the arrival of Union troops was enough to stop the violence – one soldier in East Tennessee reports finding a pregnant woman murdered, a message just below: “Thou shalt not give birth to traitors.”

The war was most painful in Border Areas and Unionist strongholds where divided loyalties made it truly a "brothers war". General Thomas was disowned by his Virginia family, who accused him of murderous treachery and would never speak to him again, even burning his portrait and refusing his money when they fell in hard times. General Grant's father in law remained "an unreconstructed rebel" that blamed Grant personally for the devastation Missouri suffered. Mary Todd Lincoln, the first Lady, had four brothers in the rebel army - and two of them perished in battle. James and John Welsh, brothers from the Shenandoah Valley, were separated by the war, James pledging allegiance to the Union and accusing John of being a traitor, while John told James that he had forsworn "home, mother, father, and brothers and are willing to sacrifice all for the dear nigger." Dr. Robert J. Breckinridge, the uncle of the Confederacy's President, remained loyal to the Union and despite his conservative tendencies he accused his nephew of being a traitor and would never speak to him again. William Goldsborough, fighting in an Union Maryland regiment, fought against his brother Charles, part of a Confederate Maryland regiment. And at Lexington, one loyal Kentuckian captured his Confederate brother.

Southern Unionists could at least strike back against their oppressors, but Union prisoners had no such luck. In 1863, as Southerners declared openly that they would re-enslave or massacre captured Black troops, refusing to treat them as prisoners of war, the Lincoln administration struck back by stopping at prisoner exchanges. "The enlistment of our slaves is a barbarity," declared the head of the Confederate Bureau of War. "No people . . . could tolerate . . . the use of savages [against them]. . . . We cannot on any principle allow that our property can acquire adverse rights by virtue of a theft of it.” Secretary of War Davis even said of Black prisoners that "we ought never to be inconvenienced with such prisoners . . . summary execution must therefore be inflicted on those taken." The issue was further aggravated by reports of the kidnapping of free blacks. Adopting a hardline, Lincoln declared in March, 1863 that "For every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works."

Breckinridge too had been radicalized. Though never a proponent of racial equality, previous to the war Breckinridge had, surprisingly enough, expressed some sympathy for free Blacks and leaned into anti-slavery. He, for example, refused to prosecute a free Black man accused of a crime unjustly (for the record, he refused to defend him either). He was willing to treat free Blacks as prisoners and return slaves if it was proved they had been free men. But now he declared that “the Negro, as an inferior race to be always subjected to the dominion of White men . . . must be put back in his natural condition of slavery as soon as possible. Once a treaty of peace has been concluded, those who had enjoyed a condition of liberty previous to the war may be returned to the United States. But all stolen property must remain in the South . . . and reparations must be offered for the property that cannot be restored.”

African Americans were routinely massacred by White Confederates, who were never prosecuted by their own government

In truth, neither Lincoln nor Breckinridge had much lust for blood, and both paled at the actions of out of control partisans. The policy of retaliation was formed as a way to deter the other side from engaging in further war crimes, but since the Confederate government had never had control of its guerrilla bands, there was little Breckinridge could do to stop them. His orders to prosecute the criminals of Canton were simply never carried out, and they were, moreover, extremely unpopular. Lincoln, similarly, had little control over Union partisans both in the Border States and the South. But both sides saw the actions of these bloodthirsty murderers as sanctioned by the other government, the natural result being that the war was simply slipping out of control in many areas. Richmond and Philadelphia could do nothing to arrest these violent developments.

Lincoln is usually seen as a man of great compassion, who presided “like a father, with a tear in his eye, over the tragedy of the Civil War.” But in the face of such outrages, of such devastation and murder, Lincoln took a rather merciless posture. As historian Andrew Delbanco says, “He directed the war without relish, but also, in his way, without mercy.” He entered the Senate in 1854 believing in the innate goodness of Southerners. But as he saw Lyman Trumbull murdered and Charles Sumner almost so, as he observed how the South applauded murder and fraud in Kansas, as he realized that all Southerners took part and approved tacitly in the terrible actions of the guerrillas, Lincoln became convinced that it would not be enough to simply forgive Southerners and welcome them back. Their entire society, being built in White Supremacy and cruelty, had to be destroyed, and a new, radical conception of justice and equality had to be built in its place.

Driven by the “fateful lighting of His terrible swift sword”, the Union government took reprisals, declaring in a circular that “civilized nations acknowledge retaliation as the sternest feature of war. A reckless enemy often leaves to his opponent no other means of securing himself against the repetition of barbarous outrage.” Lincoln himself appeared in a Philadelphia and declared that “Having determined to use the negro as a soldier, there is no way but to give him all the protection given to any other soldier. The difficulty is not in stating the principle, but in practically applying it . . . If there has been the massacre of three hundred there, or even the tenth part of three hundred, it will be conclusively proved; and being so proved, the retribution shall as surely come.” And it came, two weeks later when 30 Confederate prisoners of war were put in trial for the massacre at Canton and executed, while a further 100 were put to work digging canals for Grant.

Why did the Union, in the face of such a cost, continue the war? It came, partly, from a spirit of revenge against Southern outrages. But also, from a sinking realization that war was the only way of assuring reunion. Many Northerners believed that if emancipation was simply dropped, then the South would be willing to reunite. But bold declarations poured forth from Richmond, not only stating that the South would only make peace in the terms of total independence, but also demanding the cession of Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky. “We would rather die than give up those territories to rebel criminals”, declared many Northern editorials. Further demands, such as “reparations” for slaves liberated abounded, from less than official sources but the fears they caused were real enough. The idea of leaving the loyal men of the South, exposing them to quite literal extermination, also informed the determination of the North. More than anything, it reflects a developing view of the Union cause as a sacred crusade and the war as penance for the national sins. Thus, and despite Chesnut attacks, Lincoln and the majority of the North closed ranks, imbued with a grim determination to see the war through.

Lincoln and the soldiers of the Union came to view their cause as a holy crusade for the construction of a new nation.

This determination would be needed in the following campaign, which would decide whether the nation would survive or not.