“The Plot Against America”

“Americans play to win at all times. I wouldn't give a hoot and hell for a man who lost and laughed. That's why Americans have never lost nor ever lose a war.” - George S. Patton

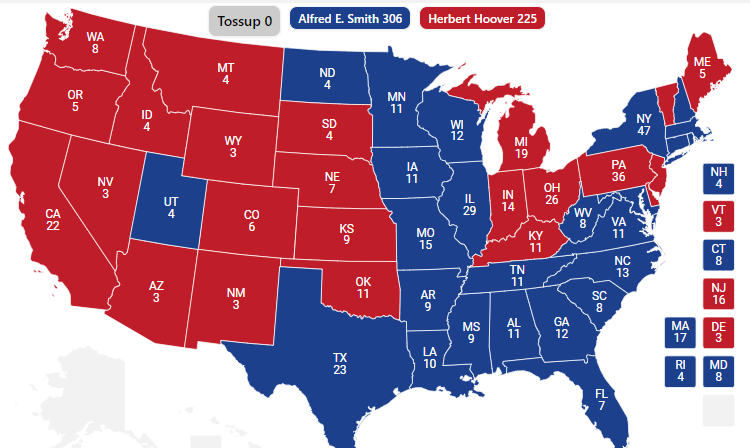

The 1932 United States Presidential election

The 1932 United States Presidential election

Alfred Emmanuel Smith had fought for twelve years to be President of the United States. When he finally achieved victory in 1932 he was left with the task of stitching up a ruined and hungry nation. Four years earlier, he lost in a landslide that had nearly torn his party in two. But then, the happy times dried up and President Herbert Hoover’s popularity imploded. It was under these terms that Smith, with the surprise death of presumptive frontrunner Franklin Roosevelt, was able to win his party’s nomination again and defeat Hoover.

Smith took the oath of office on March 4th, as the first Catholic President— a fact that made much of the country bitterly hate and distrust him. Even Hoover, widely blamed for the wholesale destruction of the U.S. economy and having overseen one of the most tumultuous terms in office since Abraham Lincoln, had made a credible showing against Smith. The new President's faith and his east coast accent made him anathema to the rural heartland. He was a devoted urban progressive who envisioned good governance as a beneficial partnership between the state, the working man, and big business. In the desperate times following the 1929 Stock Market Crash, Smith’s pushes for sensible reform satisfied nobody and infuriated many. From the angry generals watching their gallant veterans starve to the business tycoons terrified of leaving the gold standard to the fiery evangelists raving against papist influence, Smith’s country was filled with his enemies.

The failure of the proposed 20th Amendment, thanks almost entirely to anti-Catholic opposition to Smith, kneecapped the President’s ability to respond to the ongoing crises. Smith proposed a wide range of reforms to heal the nation. They fell mostly on deaf and suspicious ears. When the Glass-Steagall Act faltered in Congress because of Smith’s opposition to an insurance clause, the public blamed him for prolonging the mess he was elected to clean up. Meanwhile, another Amendment, the 21st, which would have ended America’s disastrous flirtation with Prohibition, had stalled in the states thanks to anti-Smith backlash. The many economic programs that did make it to Smith’s desk in the year of 1933 were not enough to end the American people’s woes. And what good they did was drowned out in the noise of sprawling unemployment lines and angry demagoguery.

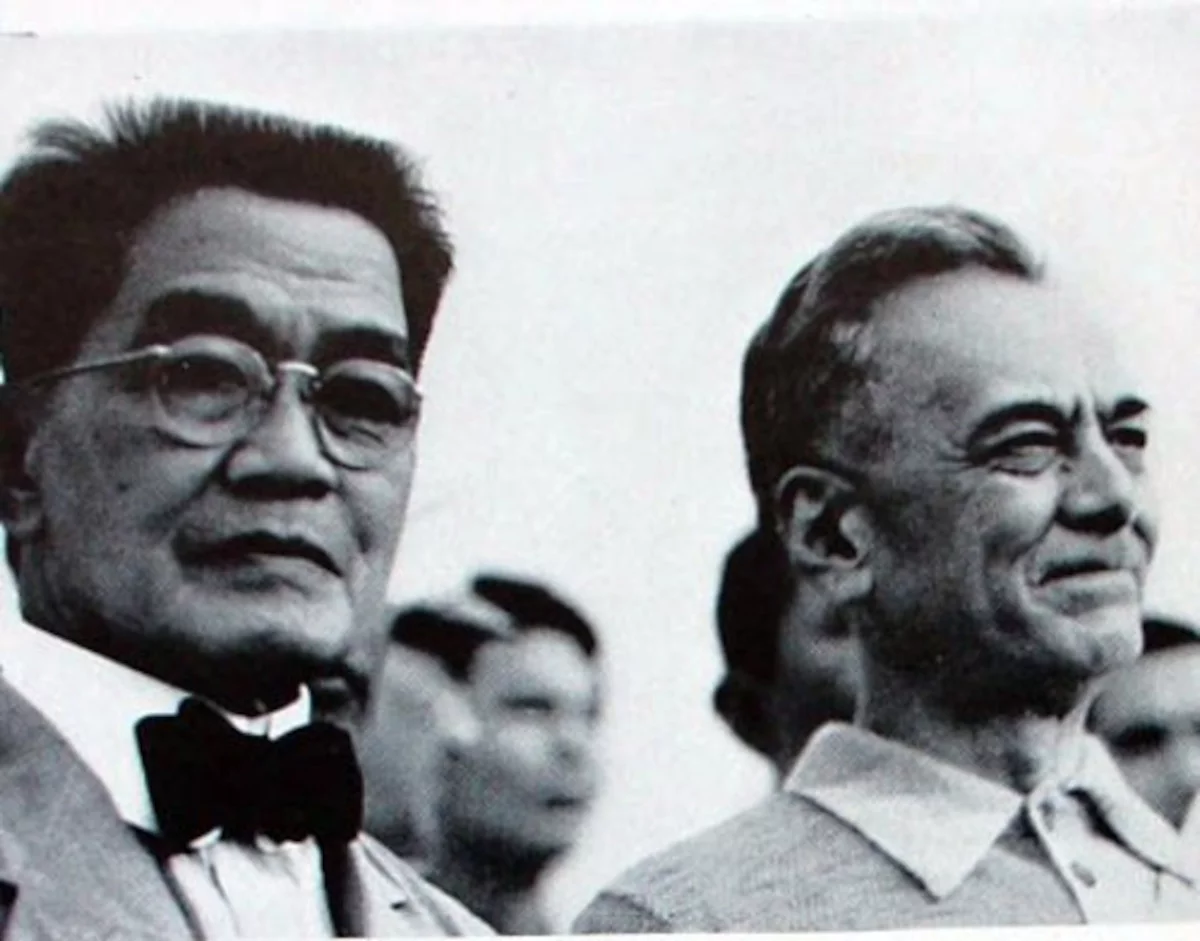

Al Smith, the 32nd President of the United States

They did, however, make an enemy of America’s invisible branch of government: the titans of industry, who had controlled it completely for the latter half of the nineteenth century and whose influence had waned but never vanished entirely. Smith’s agenda frightened big business. With millions out of work and the employment lines stretching through whole cities, big business concluded that democracy as it stood was mostly untenable. The ultimate example of this was Smith, foisted on the nation by a rabble of immigrants, progressives, and shiftless vagrants. The inevitable result of this would be a socialist revolution as seen in Russia, or a revolution of an entirely different sort.

J. P. Morgan Jr. famously told a confidante that, “democracy has given us Al Smith, who shall surely give us inflation, which shall surely give us Bolshevism.” Of the many forces that sought to destroy Al Smith, business that was the brains of the operation. They were hardly alone, however. A fellow Catholic known for his progressive economic views, the radio broadcaster Father Charles Coughlin, broke with Smith early and decried him to his millions of listeners as a “tool of the international bankers and Judeo-Bolsheviks!” America’s then nascent and repressed communist and socialist parties also were witheringly critical of the Smith administration, calling him the "feeble peace offering of a dying system". But the most obvious obstacle for Smith was how widely he was distrusted by America’s white Protestant majority, particularly in the western and southern United States. South Carolina evangelist Bob Jones had fumed four years earlier that, “I'd rather see a saloon on every corner of the South than see the foreigners elect Al Smith president.” Little had changed— only now Americans were hungrier and more desperate than they were in 1928.

Millions of Americans feared that Smith took direct orders from the Pope, and that he would soon begin taking bloody vengeance on Protestant churches. When he won, it became common practice in many communities to openly flaunt his authority. He represented the beginning of a heinous plot against America that involved the subversion of its character and institutions and consolidation under transnational elites, including the Pope in Rome and the Bolshevik government in Moscow. As economic malaise raged on, the nation slipped out of Al Smith’s fingers.

The men that shared Morgan’s sentiment about the crossroads the nation was at had long admired the workings of fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini, which in their view had achieved order and harmony and warded off communist insurgency— at the expense of its people’s liberty, but with the stakes so high, what other options were there? More encouraging for them still was Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s ascent as German Chancellor two months before Smith was inaugurated. Hitler rapidly consolidated power and would soon become the unquestioned dictator of Germany, a development that these men saw as especially promising. “America,” said businessman Gerald C. MacGuire, “needs a Hitler of our own. Just for a little while.” President Smith’s chief focus had been installing his government and putting the nation back to work again. He had done his best to ignore attacks on his patriotism and the unhappy mutterings of big business, who he viewed as a partner to be cooperated with and not an enemy to be destroyed, as they viewed him. He found himself isolated in many of his own government’s corridors of power— viewed as a foreigner in his own country, particularly to the United States military’s leading men. This is what convinced many of them that it was acceptable or even necessary to intervene.

/GettyImages-3425760-5c4ce47446e0fb000167c6d0.jpg)

European dictators Benito Mussolini (left) and Adolf Hitler (right)

Much ink has been spilled as to when this stopped being wild talk at champagne dinners or in raging Sunday sermons and became a concerted plan to overthrow the government of the United States, but by Christmas all of the major parts and players were in place. Bankers under Morgan, industrialists under automobile titan Henry Ford, and a host of political leaders ranging from fire-breathing populists to strict conservatives were united in ousting Al Smith from the White House. And in the first weeks of January, they did exactly that. Another Bonus Army, like the one that had crippled and embarrassed Hoover, descended on Washington. As it marched, it rapidly snowballed into something much, much more than Great War veterans angry that they had been stiffed again by the government. They reached the city in full force on January 19th.

And on January 20th, Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur announced to the whole country by radio that sudden developments had forced an interim government’s formation. It was not a particularly rousing speech and was almost completely devoid of details, lasting for under a minute. In fact, in the postwar period, this lead to much speculation that MacArthur had not participated in the initial coup and was only brought into the new government later. In the confusion, some even alleged that the speech was not MacArthur’s, or that the speech had not even been given at all. MacArthur, on the radio to millions of listeners, declared simply that:

There was no such joint resolution. The exact events of January 19th have been heavily scrutinized and debated, with historians unlikely to ever discover the full truth. Smith was quite clear that he received many contradictory updates as to the progress of the Bonus Army’s march. He dispatched MacArthur, as President Hoover had in 1932, to keep the peace. MacArthur apparently joined the demonstrators just before sundown, and Smith fled the White House with his family and cabinet. More curious is the role of J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Bureau of Investigation. Among those who sponsored the March on Washington, Hoover’s motives are the most difficult to discern because of the Director’s own paranoia. He was perhaps the only person in Washington who could have realistically captured Smith before he fled, which would have dramatically altered the course of world history. If Hoover was in on the planning, then how was Smith able to escape? And if Hoover was left out in the cold, then how did Smith remain unaware of the coup until it had seized the White House itself? And how did Hoover assume the leading role in MacArthur's regime he is now notorious for? Nonetheless, Hoover was instrumental in rapidly locking down the city of Washington and capturing many of its important men before they were able to grasp the full ramifications of what had happened. His services went far in establishing the new government. Most notably, Hoover arrested all nine members of the Supreme Court, even Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes.In light of the emergency which has taken control of Washington D.C., I General Douglas MacArthur, Chief of Staff of the Army, have been left with no choice but to honor our Constitution and our Christian God by putting down the lawlessness and conspiracy of my own accord. Al Smith has fled Washington D.C. after it was discovered he was in league with the Pope and Moscow. In the interim, an emergency joint resolution from Congress has vested government power in me.

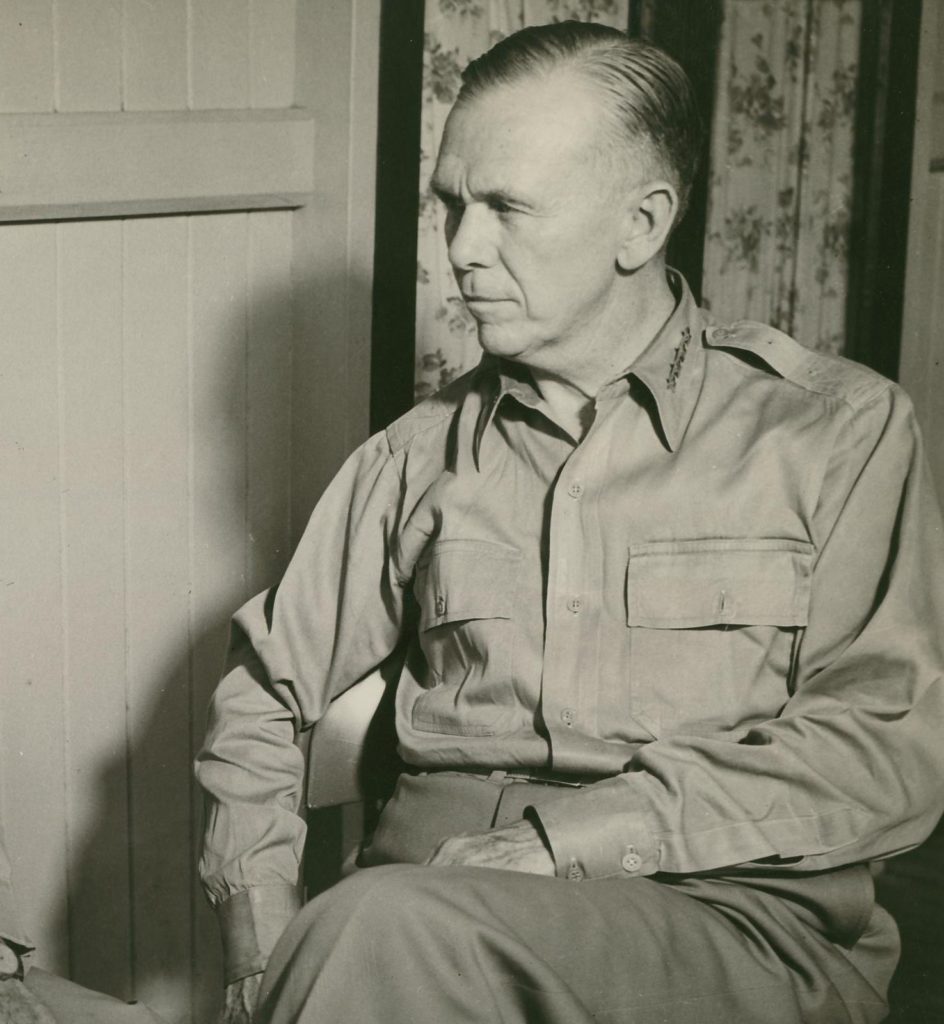

General Douglas MacArthur, 1930

MacArthur was a man that believed himself firmly destined for greatness. He was born to General Arthur MacArthur, who fought in the Civil War and Philippine War with distinction. MacArthur grew up in a western military family where he learned to shoot before he could read and graduated from West Texas Military Academy at the top his class, going on to serve with valor in the Great War. He was known for his flamboyant persona and disregard for civilian authority. Following his service in the Great War, MacArthur became Superintendent of West Point, and later Commander of the Philippine Department. In 1930, he became the Army's senior most officer. An aide called him, the most "flamboyantly egotistical" man he had ever met. And indeed, in the Army, MacArthur was most famous for his long-winded orations and fondness for pompous dressing. Nonetheless, he was an extremely talented commander that had proven himself many times over. And he also had political ambitions, although nobody, probably not even MacArthur himself, could have imagined where the general would be in 1934 and what place in American history he would carve for himself.

The mass psychology of the March on Washington has been covered ad nauseum, and many competing explanations have been offered for how it managed to get as far as it did. The general consensus among historians is that while MacArthur had many supporters in the general public and in high places, more importantly great fear, apathy, and confusion paralyzed the many men that were capable of stopping the putsch in its cradle. In many quarters, MacArthur’s coup certainly was welcomed. One preacher in southern Virginia praised MacArthur for, “his firmness of constitution, in saving the republic from the twin evils of romanism and Bolshevism.” And indeed, there were millions cheering Smith’s overthrow. More common, however, was muted alarm. The state governments, particularly those in the west, did not know what to make of the President’s sudden flight or the dashing MacArthur declaring his own government. Governor William H. Murray of Oklahoma said it most frankly to a member of his state’s National Guard: “We do not know where Alfred Smith is or what General MacArthur intends.”

The reaction of the military men in the coup’s opening hours and days can be genuinely bewildering to observers. In the leadup to January 19th of 1934, there is a shocking absence of serious insurrection plans or even particularly anti-Smith sentiments in what papers survived. MacArthur’s aid, Dwight D. Eisenhower, is on record screaming at his superior hours after the March on Washington. “You dumb son of a bitch,” fumed Eisenhower, according to defectors, “you just waged war on the most ancient republic on this earth! Don’t you fucking understand that this means war and revolution?” Eisenhower probably represented the majority of the military, particularly the army. But nearly all of its members had, if nothing else, respect for MacArthur’s abilities. Consequently, few generals fled Washington when President Smith suddenly did. While few openly supported the coup and many actively dreaded it, few of the Washington institutions and military hierarchies had been seriously disrupted in January of 1934. Consequently, inch by inch, the military of the freest republic in the world found themselves serving a coup. Diarist Mary Dothan, who was in Washington, recorded that “it is as if the whole nation has fallen into a stupor. Everyone agrees that Gen. Mac’s rule is benevolent or that he is a miscreant who shall surely be cast out without delay and without any trouble.”

The United States Capitol immediately prior to the March on Washington

Congress was out of session, and therefore was unable to coordinate a unified response. This was intentional, as the men that orchestrated the March on Washington believed Congress would be the main obstacle to their designs— as with Smith, their strategy was to force them out and seize legitimacy through the virtue of raw control over Washington. Senator Huey Long was the first to bite, permanently fleeing to his base of power in Louisiana and rapidly assembling a council of his allies. Hiram Johnson of California did something similar, far out of both Smith and MacArthur's reach. Around a fourth of Congress remained in Washington, and these men either fled or fell under MacArthur’s control. Republican leader Charles McNary was among those that refused to flee the city, either due to underestimating MacArthur or believing such a thing was beneath a member of Congress; he was never seen again. Nonetheless, many denounced the coup in the strongest terms and immediately got to work at picking up the pieces, outside of Washington. William Borah of Idaho declared that the "Nika Rioters" would be crushed with all haste and faced no prospects but unconditional surrender.

Well before the end of January, as baffling messages raced across the country and the world, a new power ruled the seat of the republic. The National-Corporate government had no constitution, no convention of state delegates, and no official proclamation date but within days its existence was hard, established fact, far more than the rival Smith government being hectically assembled in New York. MacArthur was hastily declared President of the United States.

Under cover of darkness, Smith and his wife Katie were ferried to his home base of Albany by plane. He was received by Eleanor Roosevelt, a close friend who had succeeded her late husband as governor of the Empire State. He was more unsure than anyone what had happened— someone, something, had run him out of his palace like a disgraced emperor. No one had rushed to his defense and nobody knew what had happened. Some members of Smith's entourage patently refused to believe that MacArthur had betrayed him, while others viewed the general's acts as no more than McClellanesque insubordination and not an intentional attempt to drive Smith out of office. None suspected that a whole new regime was breathing its first breaths in the very seat of American democracy. President Smith had no way of knowing that he had been victim to an American coup, the first shot fired in the Second American Civil War.

New York Governor A. Eleanor Roosevelt

Last edited:

.jpg&f=1&nofb=1&ipt=31a4fb1bea9e46990d8232daa576c46a4442c8e0fa8898b5b673c01d9d04e7b1&ipo=images)