Well that's extremely good news for the Shuttle program, NASA thankfully will not be responsible for traumatising millions of children on live TV in this timeline. With the O-ring failure mode removed, I wonder what Ken's investigation will be able to turn up, discover and improve on the program, sadly there is only so much they realistically can do to improve the overall safety of the current Shuttle architecture...

Interlude: Burn-Through

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Sound of Thunder: The Rise of the Soviet Superbooster

- Thread starter nixonshead

- Start date

True... but I'm guessing at what would make narrative sense, not statistical sense.That's not how statistics work. If this task force can push the odds from 1 in 9 to 1 in 100 that 1 in 100 could still happen on the next flight, on the 100th, or at any point in between.

Oooh I considered this. But something tells me if NASA blows up one of their birds, they're not going to be putting anything on the moon any time soon. Quick and dirty or otherwise. But, as someone earlier in the thread pointed out, it'd take a looooot of Grozas to set up Barmin's moon base plans. So, if all goes well for NASA and the Soviets have a few launch failures, of which they've honestly had suspiciously few lately, there might be just enough margin for NASA to get something actually worthwhile up there first, even if the Soviets are pushing for the same thing.What is a moon base? If it's any sort of structure visited by multiple crews the prize goes to whoever wants to go to the effort, the Soviets could do it within the next few years, long before the US gets back to the moon but might choose not to. If it's somewhere where you can do actual science and that significantly extends your stay the Soviets again have a head start and a much better architecture. But if the US goes for something quick and dirty and the Soviets go for something useful the US might just "win".

NOTS my beloved.NOTS [Naval Ordnance Test Station] accomplished a vertical landing in 1962 using their Soft Landing Vehicle! used a radar to control its variable thrust engine ^.^ Was just a small scale test demo, not exceeding 150ft in altitude IIRC, but it showed promise nonetheless!

I guess the "old" SRB end up for use Shuttle-C only.

Question is what will replace the old SRB ?

Simple modified SRB like OTL or go straight to Advance SRB ?

Last one would increase the payload of Shuttle and Shuttle-C, but is expensive...

Still issue with heat shield hit by debris during launch.

but if Mattingly continue his job austere, he encounter the issue after flight STS-27 in 1988.

(bolt hit Shuttle during launch, 700 tiles were found to be damaged including one that was missing entirely)

and the 1994 study by Paul Fischbeck, an engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

about danger of ice debris from ET hitting the Orbiter.

Question is what will replace the old SRB ?

Simple modified SRB like OTL or go straight to Advance SRB ?

Last one would increase the payload of Shuttle and Shuttle-C, but is expensive...

Still issue with heat shield hit by debris during launch.

but if Mattingly continue his job austere, he encounter the issue after flight STS-27 in 1988.

(bolt hit Shuttle during launch, 700 tiles were found to be damaged including one that was missing entirely)

and the 1994 study by Paul Fischbeck, an engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

about danger of ice debris from ET hitting the Orbiter.

Just not SRB-X, this is one of the worse ideas for a Titan replacement.Would that lead to the SRB-X if it was the case? I doubt at this time they will just close shop with their SRBs.

I love to see good exposition through story. Great work!You can tell the rest of the astronauts that this sort of thing is going to stop. I’ve been hearing too many stories of short-cuts in the program.”

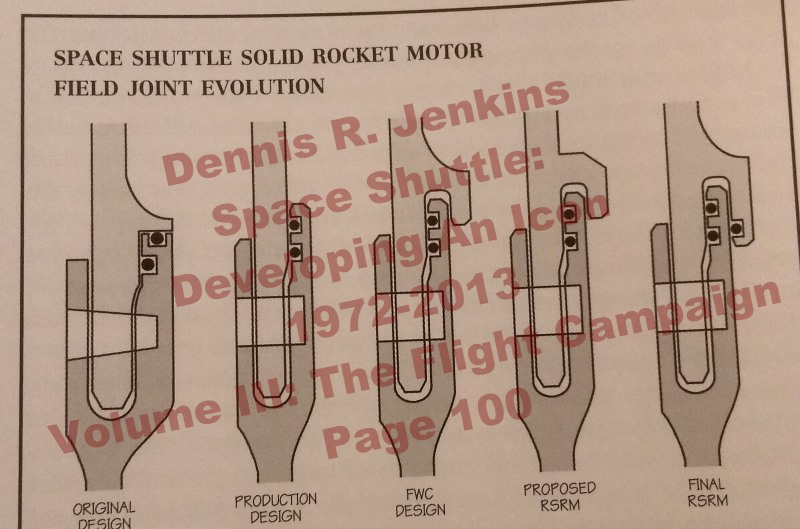

Just to remind everyone, the solution the FWC boosters had to the O-ring problem was to include a 'capture feature' that prevented the booster segments from developing a gap as they flexed during launch:

Something else to keep in mind is that each SRB segment consisted of two sections that were joined using the same type of joint, just completely covered with a liner that prevented hot gasses from getting to the joint. As a result, you can take half of the sections from the old style of boosters, and reuse them with the new sections that have the needed capture feature, and not completely retire the old sets.

Also, OTL the FWC boosters got a study contract in February of 1981, which lead to a full test firing in October of 1984. The FWC boosters give a solid 8000 lbm extra performance to LEO, which is going to be really useful for lifting shuttle payloads to higher orbits, and allowing OV-101 and OV-102 to carry their full 65k lbm payloads.

Something else to keep in mind is that each SRB segment consisted of two sections that were joined using the same type of joint, just completely covered with a liner that prevented hot gasses from getting to the joint. As a result, you can take half of the sections from the old style of boosters, and reuse them with the new sections that have the needed capture feature, and not completely retire the old sets.

Also, OTL the FWC boosters got a study contract in February of 1981, which lead to a full test firing in October of 1984. The FWC boosters give a solid 8000 lbm extra performance to LEO, which is going to be really useful for lifting shuttle payloads to higher orbits, and allowing OV-101 and OV-102 to carry their full 65k lbm payloads.

NASA knew what they needed for an actual cheap and reusable working launcher, but OMB wouldn't fund it. They knew in 1965, they knew in 1969, and in 1970, and in 1972.

Yeah. I can't really disagree with that.

All of us have been sleeping on the obvious higher calling the N1 has ahead of it, and I have been a fool not to connect the dots BeanHowitzer has left for us— after all, how can the Soviet Military pass up the proof of the power and glory of the Communist System made manifest by the might and form of a translunar atomic battleship?

https://x.com/beanhowitzer/status/1734394542336454793?s=20

https://x.com/beanhowitzer/status/1734394542336454793?s=20

Last edited:

Absent specific missions like Hubble, the STS-3XX missions don't require the orbiter to be on the pad, and since a fair number of Shuttle payloads are installed on the pad anyway there's not a rollback needed (there's actually better access to the payload bay on the pad via the Rotating Service Structure than in the VAB, I believe?). Thus, it mostly just means having the next orbiter in line for launch ready a few weeks or months earlier than strictly needed, which really isn't much of an impact at all unless you're running a very small orbiter fleet, or aiming for very high flight rate.Plus the STS-3xx missions would suck up resources, at above 15 Shuttle flights a year preping a second orbiter for every launch would be easy, but the payload carried would need to be removed, OTL STS-3xx flights were done for Station rescue, the Hubble repair mission was flown when the Shuttle fleet was largely slowed for safety post Columbia, and Endeavour was rolled back and fitted with a payload afterwards for its station construction mission

Payload canister holding Columbus rolls out of the Canister Rotation Facility

Payload canister holding Columbus rolls out of the Canister Rotation Facility

www.esa.int

Disposition of space shuttle payload canisters - collectSPACE: Messages

Source for space history, space artifacts, and space memorabilia. Learn where astronauts will appear, browse collecting guides, and read original space history-related daily reports.

www.collectspace.com

we love NOTS <3 first air-launched orbital rocket,, weird self landing stuff,, big fan of them foreverNOTS my beloved.

Yeah that's my thinking, and if you've got four active Orbiter's (assume one's in refit at any time) then the 1985 flight rate of nine can be easily maintained if you've sorted out the boosters and at least tried to mitigate the tiles. Probably a bit more than that actually, so an orbiter is never more than six weeks from the pad which should be fine for another crew stuck at Skylab with a bent bird. Especially as your literally just flying the shuttle, no cargo beyond what's in the hab section and a pile of space suits so (beyond sweating bullets about it happening twice in a row) its actually a very simple prep for a mission.Absent specific missions like Hubble, the STS-3XX missions don't require the orbiter to be on the pad, and since a fair number of Shuttle payloads are installed on the pad anyway there's not a rollback needed (there's actually better access to the payload bay on the pad via the Rotating Service Structure than in the VAB, I believe?). Thus, it mostly just means having the next orbiter in line for launch ready a few weeks or months earlier than strictly needed, which really isn't much of an impact at all unless you're running a very small orbiter fleet, or aiming for very high flight rate.

Payload canister holding Columbus rolls out of the Canister Rotation Facility

Payload canister holding Columbus rolls out of the Canister Rotation Facilitywww.esa.intDisposition of space shuttle payload canisters - collectSPACE: Messages

Source for space history, space artifacts, and space memorabilia. Learn where astronauts will appear, browse collecting guides, and read original space history-related daily reports.www.collectspace.com

Also this is the MMU era so flying a patch kit on the shuttles themselves might be a option.

Obviously a 400 mission would be much harder but if NASA plans it schedules right (and probably makes sure non station missions have the extended or even double extended duration orbiter equipment on board) it should be possible to get to the bent bird within the 16-28 day window.

Last edited:

Yeah that's my thinking, and if you've got four active Orbiter's (assume one's in refit at any time) then the 1985 flight rate of nine can be easily maintained if you've sorted out the boosters and at least tried to mitigate the tiles. Probably a bit more than that actually, so an orbiter is never more than six weeks from the pad which should be fine for another crew stuck at Skylab with a bent bird.

In OTL they managed 8 launches in 1992 and 1997 and consistently launched 7 missions throughout the period, so with 5 orbiters (at least for a while) they should be able to get to 9 or 10 missions a year at a post Challenger level of caution and while the first launch of the STS is extremely expensive by the time you get to the 10th the zero base study suggests the marginal cost is relatively affordable at roughly $87million against an Atlas II at $84 million and the STS deliver over 4 times the payload to LEO. Plus with Shuttle-C happening in this tl you are going to have extra External Tanks and Boosters being made driving down the unit cost on those. So assuming the safety program works you are going to have a relatively affordable, fairly dangerous launch system. Which isn't ideal but it's better than OTL.

Of course, for the STS-3xx mission profile, there's also the factor that they're only needed for orbits where it'd be impossible for the Shuttle to make it to Skylab-B or its replacement - if they can make it to Skylab-B, then they could potentially use the station as a stand-in for the STS-3xx orbiter, with the ACRV as the crew's ride back to the ground (and with the bent bird coming back on automatic control from the ground). At which point, you repurpose what would have otherwise been the STS-3xx bird, or even just the next Skylab-B flight, to replace the ACRV and parts that the bent bird needed to cannibalize.

Well, the O-rind erosion described in the post is exactly as was actually observed IOTL on STS-2 (see p.126 of the Rogers Report). ITTL, it is instead observed on STS-3, which has Ken Matingly in command ITTL. He sees the burn-through issue in the post-mission report, and just happens to be an old Apollo buddy of the new NASA Administrator, so has a way of by-passing normal channels to escalate his concerns. Borman, as a former astronaut and having recent experience in an industry that puts a premium on flight safety, is receptive.What's the chain of events that led to this. Is it just a random butterfly? Or something that requires Borman to be in the big chair?

Would that lead to the SRB-X if it was the case? I doubt at this time they will just close shop with their SRBs.

USAF considers itself pretty well covered ITTL's early '80s, with Shuttle, Shuttle-C and the soon-to-be-privatised expendable launhers staying around, so isn't so interested in spending their budget on yet another launch vehicle. Of course, Congress has been known on occassion to override technical considerations when it comes to launcher design...depends on commerical viability and USAF interest, most rocket developments were funded through the military (Atlas, Delta), the OmegaX failed to get funding and was canceled

Not to mention the refurbishment and transportation costs, and the need for a 39 a or b pad to launch

I sure as shit don't want the thing flying with crew, Ares-1 was a deathtrap, thank god it never entered use

Considering the superb quality of your writing, I really appreciate this!I love to see good exposition through story. Great work!

For those who haven't yet seen it, I strongly recommend checking out Ocean of Storms. IMO it's literally the best written space timeline on these forums.

Awesome!All of us have been sleeping on the obvious higher calling the N1 has ahead of it, and I have been a fool not to connect the dots BeanHowitzer has left for us— after all, how can the Soviet Military pass up the proof of the power and glory of the Communist System made manifest by the might and form of a translunar atomic battleship?

View attachment 874862

View attachment 874863

https://x.com/beanhowitzer/status/1734394542336454793?s=20

Part 2 Post 3: Nuclear Dawn

Part 2 Post 3: Nuclear Dawn

“America has always been greatest when we dared to be great. We can reach for greatness again. We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful, economic, and scientific gain. Today, I am directing NASA to develop a manned lunar base and to do it within a decade.”

- President Ronald Reagan, State of the Union address, 26th January 1982

++++++++++++++++++++

The return of the Zvezda 4 cosmonauts, as expected, provided a much-needed propaganda boost to the home of World Socialism. Television pictures of the three men being helped out of their capsule and gifted flowers by local children were broadcast on evening news bulletins worldwide, and congratulatory messages flowed into Moscow from all corners of the globe. After ten days in isolation for a period of “precautionary quarantine” (but surely Apollo had proved there was no danger of infection?), Leonov and his crew re-appeared at a public parade in Red Square on 24th September 1981, in which Defence Minister Ustinov awarded the men Hero of the Soviet Union medals. Ustinov conveyed the warm greetings of Comrade Brezhnev, who unfortunately was unable to attend due to a mild cold, which he did not wish to spread to the new heroes.

After Red Square, the crew embarked on a global tour, starting with the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe. These generally involved public parades through the capital, but there was a notable exception in Warsaw, where Leonov, Popovich and Voronov were received in private by the new Prime Minister, Wojciech Jaruzelski. Moscow had recently cut energy exports to Poland in an attempt to strong-arm the United Workers’ Party into clamping down on the strikes and demonstrations that were becoming endemic in the country. Sending Soviet cosmonauts to a large public event in the capital was seen just as likely to provoke a riot as a celebration.

While the Zvezda 4 crew provided a confident, heroic face for the Soviet space programme, behind the scenes other, darker projects continued to progress. On 18th January, as Leonov arrived in Cuba, Groza vehicle N1-25L was being checked out at Baikonur Pad 38. The checks were more extensive than had become usual for an N-1 launch due to the extreme sensitivity of the payload, which was the latest iteration of the Zarya MKBS space station. This third station would be powered by the 50kW EYaRD 1 nuclear reactor, which had finally completed qualification testing and was now ready for space.

Glushko knew that any accident would be far more radioactive to him politically than the currently dormant reactor. The generals were already questioning the enormous costs and limited military utility of Zarya, and any sort of incident could be enough for them to pull the plug on the whole programme. With development of his kerolox Vulkan rocket stalled by engine problems and budget cuts, even as Mishin as Kuznetsov reaped plaudits for their moon mission, Glushko’s reputation as an effective Chief Designer was on the line.

Zarya 3 was expected to provide a jump in capabilities over Zarya 2 comparable to that between Almaz and Zarya. Whereas Zarya 2’s radar could only be operated when the station’s solar panels were in sunlight, Zarya 3’s nuclear reactor would provide a steady stream of electrical energy allowing its SAR payload to be operated over the entire orbit. It also gave the necessary punch to test out more exotic weapons, such as a number of laser and particle beam weapons that had been in development since the early ‘70s. Although none of these devices were anything close to operational in the early 1980s, there were useful experiments that could be done in space. This would become especially true once Baikal added a capability to return prototypes to the lab after testing, but useful work could be done even without the shuttle, using modified Slava FGB modules that would dock and draw power from the station’s reactor.

Zarya 3 launched aboard N1-25L on 20th January 1982. Despite the various enhancements being planned for the Groza rocket, vehicle 25L was a standard 3-stage all-kerolox N1F. By mid-1981 Kuznetsov was ready to introduce his enhanced NK-35 engines to the first stage, the increased thrust of which would allow the removal of the inner six engines of the Blok-A. However, the high profile of the crewed Zvezda launches and the sensitivity of Zarya’s nuclear payload meant that their introduction would have to wait for a less critical payload. This conservatism paid off as, although two NK-33’s of the Blok-A were shut down prematurely, the launch was otherwise uneventful, and Zarya arrived in its 56 degree orbit as planned.

Two days later, following a detailed remote check-out, Glushko’s engineers commanded the deployment of the EYaRD reactor. Housed in an armoured capsule to protect it in the event of a launch mishap, the five tonne reactor pod and its biological shield were pushed out from the rear of Zarya’s shortened Experiment Compartment on an extending boom. There followed a full month of careful checks before, on 1st March 1982, Zarya’s power plant was activated, achieving criticality as the most powerful nuclear reactor ever to fly in space.

The fact that Zarya 3 was nuclear powered had been announced in advance, so as to avoid surprising the US military. The reactor’s activation would be immediately visible to American technical assets, as the station’s thermal and nuclear radiation signatures jumped. Given the high tensions between the superpowers at that time, and based on experiences with their own missile warning systems, there were concerns that US defences could be accidentally triggered.

The public announcement reduced this risk, but generated almost unanimous condemnation across the globe, which only intensified following the launch. Governments in Western Europe and much of the non-aligned and US-aligned world protested the use of nuclear power in space, and there were spontaneous protests outside Soviet embassies and at other locations. One of the more high-profile of these was at Greenham Common, a Royal Air Force base in southern England, which for six months had been the site of a “Women’s Peace Camp” protesting the deployment of American cruise missiles to the UK. Up to that point, the protest had been firmly directed against perceived US aggression, but following Zarya’s activation an increasing number of placards appeared denouncing both superpowers for nuclear brinkmanship.

Regardless of the concerns of Western environmentalists, the Soviets pressed on with their mission, and on 15th March the first crew were launched to the station aboard Slava 10. This initial mission lasted for just under two months, and focussed on bringing the station fully online and demonstrating the new procedures involved in operating a nuclear powered facility. An early example of these procedures was the docking approach, which saw Slava observe a much larger keep-out zone around the station than had been the case for earlier missions. The final five kilometres of the approach were kept within the narrow cone of the reactor’s radiation shield, bringing the TKS vehicle to a docking at the axial port of the station’s new multiple docking adapter module. Leaving the shadow cone would not be fatal, the engineers on the ground assured the crew, but it would result in elevated exposure levels that could mean the cosmonauts being grounded for medical reasons upon their return.

The Slava 10 mission lasted for just over a month, before the crew departed in their VA, leaving the FGB docked at Zarya 3’s single docking port. A week after the crew departed, the FGB was undocked under ground command, and directed up and away from the station in a direction opposite from the Earth. It soon passed outside of the biological shield’s radiation shadow, allowing measurements to be made of the radiation environment close to the station, verifying the ground models. This task complete, the uncrewed module was commanded to a destructive re-entry.

The next visitor to the station was Gavan (“Harbour”), a modified Slava FGB module with the VA replaced by a spherical docking node containing five ports. Launched without a crew, Gavan docked with Zarya in early June 1982. As well as allowing multiple ships to dock at once while remaining within the shadow shield cone, Gavan would allow specialised modules to be added, as well as providing additional attitude control capabilities.

With Gavan secured to the station, the next crewed mission was launched in August on Slava 11. This mission would mark the start of a period of permanent occupancy of the Soviet station. Only a few days into the mission, the crew used the the new Lyappa, or Automatic Re-docking System, arm to swing Slava 11 to Gavan’s Y+ port, freeing the main Z+ port to receive further Slava transports or specialised modules.

Apart from these operational tests, the initial phase of Zarya 3 operations continued the military focus of the previous Zarya 2 station. Slava 11 was followed by two more missions in 1982, with all of them crewed by military cosmonauts from Glushko’s pool of Air Force pilots. Experiments focused on military observations, in particular with Zarya’s powerful radar, which was used to track US Navy fleets through the cloudy skies of the wintertime mid-Atlantic and in the Mediterranean. Optical observations tended to target Afghanistan and the surrounding countries, especially along the border with Pakistan. The presence of cosmonauts allowed for real-time re-tasking of observations based on what they could see, while the steady flow of electrical power from Zarya’s nuclear reactor allowed for continuous operation of the radar, even when the station was in eclipse. Although there remained little benefit compared to uncrewed platforms when considering the cost of Zarya operations, as well as its unfavourable orbital inclination, the station’s contribution was not negligible, and the flow of data through the encrypted Avora link were greedily consumed by GRU analysts in Moscow.

By early 1983, however, military needs were starting to take a back seat to political imperatives. The crew of Slava 14, launched in March 1983, included both the USSR’s second female cosmonaut, Mila Pushkaryeva, and the first ever non-Soviet, non-US space traveller, the East German pilot Karl Heinermann. This was widely - and correctly - seen as a pre-emptive response to US plans to launch a female astronaut and a West German on the upcoming STS-8/Skylab 6 mission, which launched just one month later. With the uncrewed Zvezda 7 mission launching that same month in preparation for the next Soviet lunar landing, the perception that the USSR was dominating the Space Race continued to grow.

Why is there so much pushback against the nuclear reactor? Many nations previously flew RTGs powered crafts to orbit and beyond?

Still, there's finally a space station that uses nuclear energy to power itself, not like OTL were for all the funding and research going into them, they all ended stillborn/axed.

Still, there's finally a space station that uses nuclear energy to power itself, not like OTL were for all the funding and research going into them, they all ended stillborn/axed.

Why is there so much pushback against the nuclear reactor? Many nations previously flew RTGs powered crafts to orbit and beyond?

My sense is that Nixonshead might be overstating how much there would be in the way of protests, but he is not wrong for thinking they would be *significant.* Every single mission NASA launched with RTG's drew significant protests in those years (see Galileo for example), and this station is something far more robustly nuclear, and it's in low earth orbit, not heading for Jupiter! I have to say, even I am a wee bit uneasy about what happens when that thing does an uncontrolled reentry (which is the likely outcome, eventually) . . .

This period was really the peak, in many ways, of the popular anti-nuclear movement across the West.

Heads up to @Matt Wiser, to whom this is a topic of special interest and passion.

Last edited:

This is manned station in low earth orbit, not deep space probe that fly unmanned.Why is there so much pushback against the nuclear reactor? Many nations previously flew RTGs powered crafts to orbit and beyond?

For mass reason the Reactor shielding is only one side toward Space station to protect it crew.

Mean everything pass the station reactor outside the shielding, get very high radiation dose

more here

Radiation - Atomic Rockets

Given the ties that a lot of anti-nuclear movements, especially in Europe, had to Soviet agents, I imagine quite a few Soviet agents in Britain and West Germany, etc. had their work cut out for them trying to the useful idiots why Zarya 3 is good, actually. At least it advances the state of the art. I imagine there's probably some engineer team in the USSR scheming about a Groza-launched nuclear-electric probe to the outer solar system.

Share: