The tension that existed throughout the 1950s and early 1960s in Japanese politics and society failed to give way in the late '60s and throughout the '70s, despite the consistently strong performance of the Japanese economy and the resultant rise in living standards for the average citizen of the Land of the Rising Sun. A major driver for this was the leftist student associations. The Zengakuren engaged in constant mitosis, schisms splitting them into smaller and smaller, and increasingly more radical, and often violent, groups. The various Zengakuren factions did not have a monopoly on student political action, however. By the end of the decade they had largely been eclipsed on the campuses themselves by the emergent All-Campus Joint Struggle Committees, or "Zenkyōtō". With leftist militancy in the ascendancy on Japanese campuses, a wide array of forces of reaction began to rally against them. Aside from the police, the students were opposed also by various groups affiliated with the Yakuza crime syndicates, as well as the followers of influential writer Yukio Mishima.

The first Zenkyōtō of note was the one founded at Waseda University in 1962. Whilst initially founded in opposition to construction plans for a new student hall, but soon shifted to demonstrating against a proposed raise in tuition fees. These demonstrations were interspersed with violence between the students and police. The incidents at Waseda University would not subside until June 1966. The organisation of Zenkyōtō would soon be imitated by students throughout Japan. Disputes concerning tuition fees, university management corruption and the use of violent guards on campus (often recruited from far-right groups or criminal organisations) would prompt students to gather in "Kyōtō Kaigi" ("action committees") which would organise against the university authorities.

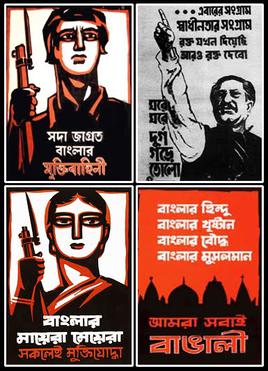

Zenkyōtō students demonstrating at Hibiya Park

In May 1968, a demonstration was held in Nihon University, traditionally the most conservative university in the country, as a reaction to the university authorities' lack of transparency surrounding the expenditure of 3400 million yen. On May 27th, the Nihon University Zenkyōtō was formed by Akehiro Akita, who also was its first chair. Despite most universities' Zenkyōtō being dominated by radical leftists, the elite Nihon University's Zenkyōtō consisted of anti-Communist and non-sectarian radicals. In order to negotiate between students and authorities, university authorities held a conference at the Ryogokan Auditorium on September 30. 35,000 students attended the rally. After 12 hours, the authorities accepted the students' demands, leading to the resignation of the university directors involved. However, following this capitulation, Prime Minister Eisaku Sato declared that "establishing relations with popular gangs deviate from common sense". In response, the Nihon University authorities reneged on their commitments to students. Provoked by this volte-face, students sports associations began to riot in Ryogoku Auditorium. Riot police were mobilised and stormed the auditorium. With the violence halted, students would eventually resume classes, but in an enclosed compound ringed with a barbed-wire fence, which was soon given the popular epithet of "Nihon Auschwitz".

Meanwhile, at Tokyo University, a dispute arose over the status of graduate medical students. The new Medical Doctor's Law had restricted employment opportunities and a judgement on militant students by the university's board of directors which furthered threatened these students' future prospects led to mass protests. This provoked the establishment of a Zenkyōtō, which would soon become the epicentre of left autonomist political action in Japan. Students occupied the Yasuda Auditorium, barricading it and battling the police with staves. In January 1969, 8500 police were called to take on the protestors. Throughout the country, Zenkyōtō were established in solidarity with the one at Tokyo University. Operating independently from the Zengakuren. Committees were organised by levels (students, staff, researchers etc.) and by departments (humanities, medicine, literature etc.). Each committee would operate with a degree of autonomy within a confederal structure in cooperation with the other committees. Committee members participated in debates, and openly voted by a show of hands, in a form of direct democracy. A National Federation of Zenkyōtō was set up at Hibiya Park in September 1969. However, Yoshitaka Yamamoto, leader of the University of Tokyo Zenkyōtō and chair of the National Federation, was arrested. The genesis of the National Federation of Zenkyōtō was a result of the wide proliferation of autonomous Zenkyōtō in universities all over Japan, from Tokyo to the most far-flung provinces. Initially focused on issues specific to their university that stood beyond the jurisdiction of the Zengakuren councils, experiences with the violent suppression of their demonstrations by riot police radicalised them. The Zenkyōtō students were galvanised against the concept of universities themselves, conceiving them as "factories of education" embedded in "imperialist forms of management" and characterised faculty councils as "terminal institutions of power". To the student radicals, university autonomy was an illusion, and universities should be dismantled through violent political action, as summarised by their motto "

daigaku funsai" ("smash the university"). The Zengakuren factions had been an intermediary stage between the 'Old' and 'New Left', being anti-capitalist, often anti-Soviet and engaging in self-criticism and anti-state action, they still followed the Leninist principle of "democratic centralism", taking orders from an established hierarchy within the faction. By contrast, the Zenkyōtō were truly a "New Left" movement, eschewing democratic centralism in favour of broad-based decision-making and ideological purity over pragmatism. Observers noted that the Zenkyōtō movement began to adopt an almost religious degree of zealotry and ideological puritanicalism. It is no surprise that the most influential academic figure vis-a-vis the Zenkyōtō movement was Takaaki Yoshimoto, who was commonly referred to as a "prophet".

Ideologically-driven infighting would intensify as the Zenkyōtō movement began to lose momentum. Many of the issues with universities were stuck in stalemates, as university authorities were unwilling to negotiate, aware that the Zenkyōtō would continue to push for the abolition of the universities anyway. In August 1969, the Act on Temporary Measures was passed by the Japanese Diet, allowing universities to unilaterally mobilise riot police units against the students. The Act would come into effect in late 1970. The lack of nuance or willingness to compromise weakened the Zenkyōtō movement. Whilst initially a thriving autonomist movement, it soon alienated those outside the National Federation of Zenkyōtō. They deemed everyone complicit in the university system, including lower administrators, as "

kagaisha" ("victimisers"). During the 1968-69 protests, the Zenkyōtō students had driven Yoshimoto's rival Masao Maruyama ou of the university system. Maruyama would retire in 1971. The Japanese university conflicts of the late '60s held a wider significance than mere disruption of the academic life of the country. Unlike the Zengakuren, which were largely comprised of undergraduates, the Zenkyōtō broadened the scope of student protest - postgraduate students, concerned at the increasingly limited and restricted employment opportunities in a Japan dominated by major corporate and industrial conglomerates, were a major force in these autonomous student federations. Even some members of staff at the universities also engaged in political organisation and rebellion against the university system. Although the Zenkyōtō largely operated parallel with the Zengakuren, there was some overlap of course: most notably the November 1968 hostage situation, where members of the Kakumaru-ha Zengakuren faction took nine professors hostage. Several of the professors were beaten and interrogated, with the hostage-takers demanding that they "admit" their role as instruments of imperialism. Other groups would also become involved in the following stand-off with police, including the Shaseidō Kaihō-ha and the Minsei Dōmei, a JCP-affiliated Zengakuren clique.

The left-wing student movements in Japan (both Zenkyōtō and Zengakuren) must be understood as part of the global '68 movement of the newly-matured "baby boomer" generation, but there was a distinct militancy that arose out of the post-war Japanese context. The generation that was coming of age had no memory of the deprivation of the Second World War and the immediate post-war years. They did see Japan incorporated into an American-led world order defined by capitalism and, in their eyes, the commodification of everything, including human experience. Furthermore, the setbacks experienced by the American-led "Free World" in other parts of Asia led many young Japanese to the conclusion that their homeland had been "shackled to a corpse". Furthermore, the discrediting of pre-war Japanese imperialism was met with impassioned reactions on both sides of the political spectrum. Whilst the older Japanese who had lived through WWII largely saw the imperialist project as ultimately foolish and self-destructive, preferring the ruling LDP's project of pacifism and economic development, to younger Japanese who hoped for something more meaningful than simply accumulating more goods, Japanese imperialism was not a fully resolved issue. On the left of the political spectrum, the student rebels of the 1960s and early 1970s saw around them a society which engaged in post-imperial arrogance, largely failing to acknowledge the bloodshed that Japan had unleashed on the other nations of East Asia. They saw Japanese imperialism as switched for a lieutenant role in the global American imperialist project. In that worldview, the Japanese elite were

compradors, enriching themselves on the work of the ordinary Japanese and kowtowing to American interests. The emergent right-wing reaction to the new order in Japan was to look back favourably on this era of imperialism; to them it was not only wrong for Japan to bow to a foreign power in the United States, but they saw the democratic government as weak-willed and decadent, too 'soft' to suppress the communist threat emerging from the universities. Many of these right-wingers hadn't lived through the bloodshed of the Second World War. They of course knew of Japan's defeat, but they saw not the folly of Japanese militarism. They saw an honourable death in the service of the Emperor preferable to the meaningless, materialist life of the modern, capitalist Japan. Whilst the

todestrieb of the far-right was not an unusual element of the psychology of the extremist, in Japan it took a particularly aesthetic flavour, especially amongst the acolytes of writer Yukio Mishima. Whereas the fascist instinct in the West was often driven by a desire to dominate, to manifest the brutality of the darkest corners of the human psyche, in Japan there was a certain perceived harmoniousness to it. The tradition of bushido, the code of conduct of the samurai of ages past, glamorised the concept of the triumph of personal will, duty and self-sacrifice. To those enamoured with these ideas, their actions did not seem thuggish. In reality, however, their violence against Japanese leftists and cooperation with organised crime syndicates seemed to indicate the opposite. Like the samurai, they had a certain self-righteousness to their aggression and contempt for those they deemed below them.

Yukio Mishima was a character whose internal turmoil coexisted with a rapidly changing, and often disorienting, world around him. Raised by a stern military father who was critical of his 'effeminacy' and a doting mother, Kimitake Hiraoka, who would later go by his pen name Yukio Mishima, fell in love with the traditional Kabuki and Noh theatre styles at a young age. His attraction to traditionalist Japanese literary styles would not end there. Whilst in secondary education, he developed a passionate appreciation for classical Japanese

waka poetry. As a teenager, he was taken under the wing of Zenmei Hasuda, a member of the board of prestigious literary magazine Bungei Bunka, who highly praised him in the magazine: "this youthful author is a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history. He is much younger than we are, but he has arrived on the scene already quite mature". Hasuda was an ardent nationalist and fought for the Japanese Empire in China in 1938, and despite his relatively advanced age was recalled to active service in 1943 to fight in Southeast Asia. At a farewell party, he uttered words that would carry a great weight with Mishima: "I have entrusted the future of Japan to you".

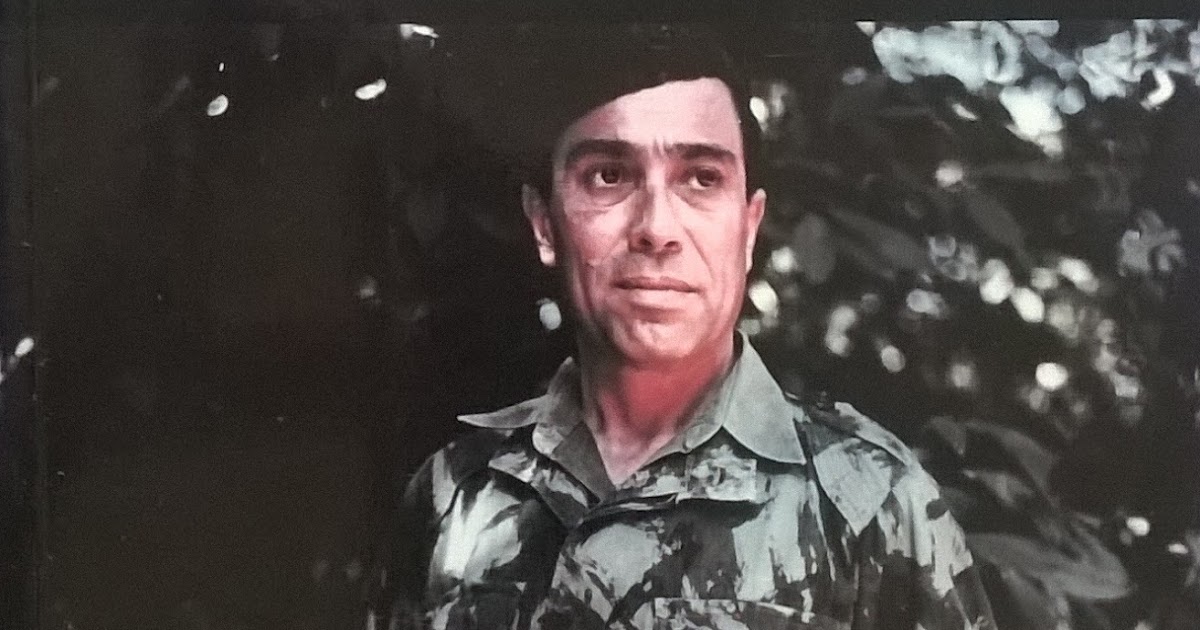

Yukio Mishima, one of the most influential (and bizarre) figures of the postwar Shōwa era

Mishima was drafted into military service in 1944. He barely passed his physical examination, and was classified as a "second class" conscript. During a medical check in 1945 on his day of convocation, Mishima was suffering from a cold, which was misdiagnosed by the doctor as tuberculosis. As a result, he was declared unfit for duty and sent home. Mishima's failure to be deployed was one of many instances in Mishima's life which contributed to an inferiority complex. He had been mocked by his school's rugby team for his membership in a literary society. He was naturally a man of slight frame, and was not particularly vigorous. His father had criticised him as a "sissy" as a child. His diaries also detailed several instances of homosexual love during his life, none of which were acted on, and which proved to be a sensitive topic with his wife when later brought up by biographers and journalists. After the war, as a result of this crisis of masculinity, Mishima would become obsessed with physical fitness, particularly bodybuilding. For Mishima and his mentor Hasuda, the surrender of Japan and Emperor Hirohito's declaration of mortality were traumatic events. Mishima, who was devoutly Shinto, vowed to 'protect' Japanese culture. He wrote in his diary: "Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able to contribute to world culture 100 years from now". Zenmei Hasuda, deployed in Malaya, shot dead a superior officer for criticising the Emperor before killing himself. A few months later, Mishima's sister died of typhoid fever. Around this time he found that Kuniko Mitani, the sister of a classmate who Mishima hoped to marry, was engaged to another man. This string of traumatic and disillusioning experiences changed Mishima forever. Although he had shown some interest in the pursuit of an honourable, meaningful death before (telling his mother that he had hoped to join a "special attack" unit in the IJA), the loss of his mentor, his beloved sister, and his hope for a marriage with Kuniko Mitani reinforced his drive to make some meaning out of his life. Domestic bliss was no longer an option. He developed a great sense of anger against the progressive literary and academic establishment in the post-war period. American-imposed bans on any "reminiscent" portrayal of Japanese militaristic nationalism left Japanese literature almost entirely monopolised by progressives. Many of the literary figures who Mishima respected were denounced as "war criminal literati". Despite the opposition of some in leftist literary circles, Mishima's postwar works, both plays and novels, were well-received by the public and made him a major public figure, an "enfant terrible" who revived the Japanese Romantic literary style that had dominated the literary landscape of the 1930s. Many of his famous works prior to 1960 were very popular, and were denounced by left-wing academics who noticed the seed of conservative ethics, but it was until the Anpo protests that Mishima's works became undeniably political in tone. Mishima criticised Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi for subordinating Japan to the United States, but reserved harsher criticism for the Japanese Communist Party and the Zengakuren organisations, seeing the treaty issue as a Trojan Horse for promoting their own ends. Shortly after the Anpo protests, Mishima made several works that lionised the ultranationalist army revolt of the February 26 Incident.

Mishima had particular hatred for Ryokichi Minobe, who was a communist and the governor of Tokyo beginning in 1967. Mishima had influential connections within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, and was asked by several senior members to run for the position of governor, but at this time, Mishima didn't seek a career in politics. This would later change [177]. That year, Mishima and his wife would travel to India, where Mishima became enamoured with the spirituality of Indian culture and the determination to maintain Indian cultural identity in the face of Westernisation and modernisation. Whilst in New Delhi, he befriended a colonel in the Indian Army who had seen action against the PLA in Tibet. He warned of the dangerousness of the Chinese troops, contributing to Mishima's anxieties about Chinese communist expansion. Mishima stated in his

The Defense of Culture, that the postwar era was one of fake prosperity: "In the postwar prosperity called Shōwa Genroku, where there are no Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Ihara Saikaku, Matsuo Bashō, only infestation of flashy manners and customs in there. Passion is dried up, strong realism dispels the ground, and the deepening of poetry is neglected. That is, there are no Chikamatsu, Saikaku, or Bashō now." From 12 April to 27 May 1967, Mishima underwent basic training with the Ground Self-Defense Force. He had initially wanted to train for six months, but was met with resistance from the Defense Agency. Mishima utilised connections of his and eventually it was settled that Mishima would secretly train for 46 days. From June 1967, Mishima, along with other right-wing figures, promoted the creation of a 10,000 man "Japan National Guard" (

Sokoku Bōeitai) as a civilian militia to complement the JSDF. Mishima began leading groups of right-wing students, having them go through training with the aim of having them form an officer corps as the National Guard expands. Alarmed by the 1968 riots of the Zenkyōtō, Mishima and other right-wing figures signed a blood oath to die if necessary to prevent a left-wing revolution in Japan. With a lack of interest in the National Guard amongst the Japanese public, Mishima formed the

Tatenokai ("Shield Society"). The Tatenokai was essentially Mishima's private militia, composed mostly of right-wing college students and which spent much of their time with physical training and practicing martial arts. Initial membership was 50, but it would soon expand to several hundred [178]. The Tatenokai would, in the early 1970s, regularly engage in battle with left-wing militant groups in street fighting. This was largely enabled by Mishima's successful campaign for the governorship of Tokyo. Mishima was a reluctant politician, but had finally capitulated to requests by right-wing members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party to run against the communist governor Ryokichi Minobe, largely due to increased concerns about the vulnerability of Japan to leftist revolutionaries as American military presence wound down. The doveish US President Chuck Percy had renegotiated the US-Japan Security Treaty, removing US forces from mainland Japan (limiting them only to Okinawa) and abandoning limitations on the Japanese armed forces. Within the Liberal Democratic Party, there had been debate about whether to alter the pacifist elements of the Japanese constitution. In any other time the issue probably would've split the party in two, with the right faction strongly in favour of expanding the military whilst the centrists (there was no real 'left' per se in the LDP) sought to focus solely on economic development and normalisation with Korea and China. The social turmoil of the time would keep the party together, even if this internal turmoil remained. The right of the party sought through Mishima to continue to strengthen their views in order to seize control of the LDP and promote rearmament and anticommunism. Mishima narrowly defeated Ryokichi Minobe in the 1971 Tokyo gubernatorial election. To this day it is debated how much the close result in favour of Mishima was influenced by the meddling of Yakuza gangs, most notably the Yamaguchi-gumi and Sumiyoshi-rengō syndicates. Both of these Yakuza groups had tendrils in certain labour unions and thus were able to effectively mobilise their resources to intimidate political opponents. Their underground connections would also make them key in the efforts to suppress the left militants of the 1970s, able to engage in activities beyond the scope of the police and leveraging both their resources and their capacity for violence to secure concessions from the civilian government in exchange for assassinations against leading left terrorist figures.

By 1968, Japan had become the second-largest economy in the 'Free World', surpassing that of West Germany. The United States returned the Ogasawara Islands to Japanese sovereignty. Moscow and Tokyo had been in negotiations about the return of Shikotan and the Habomai Islands in the Kurils, but these had stalled with the Soviet condition that the American base in Okinawa must be shut down. In December 1970, a major riot against the American military presence on Okinawa flared up in the city of Koza. By this time, the American and Japanese governments had agreed that Okinawa would be transferred to Japanese sovereignty in 1971, but the locals were enraged by the revelation that a significant US military presence was to remain. The Okinawans had been soured on the American presence as a result of a number of incidents, including extortion, assault, rape, theft and criminal nuisance by US servicemen, none of whom were punished for their misconduct. 5,000 Okinawans clashed with roughly 700 American MPs. Fortunately there were no deaths, but 60 Americans and 27 Okinawans were injured. Some rioters even broke into Kadena Air Base and burning down several buildings inside. The riot fizzled out overnight. A year later, a Zengakuren demonstration turned into a riot in Tokyo, against the terms of the Okinawan return agreement, seeking a full departure of US military personnel. A month later, Okinawa was returned to Japan, albeit with US military bases still on Okinawan soil.

Despite the efforts of the right-wing forces in Japan, the Japanese Communist Party had its strongest showing ever in the 1972 election, winning 38 seats in the Diet.

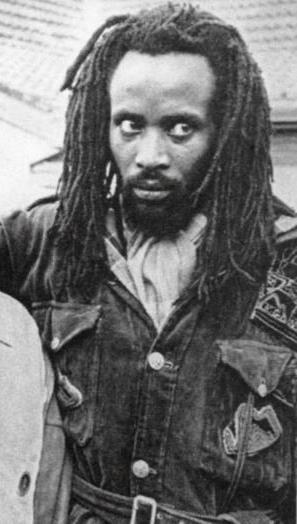

Fusako Shigenobu, leader of the Sekigun-ha (Japanese Red Army)

Emboldened and increasingly radical, the Zengakuren organisations continued to fracture. In 1963, the Marugakudo group had split into the "Central Core Faction" (

Chūkaku-ha) group led by Kuroda Kanichi's former right-hand man Nobuyoshi Honda; and the "Revolutionary Marxist Faction" (

Kakumaru-ha) cell which more staunchly followed Kuroda's line. By the mid-1970s, these two groups were in outright warfare against each other. In 1975 there were 16 deaths in this conflict alone, including the assassination of Honda. Between clashes between each other and with Yakuza groups and the Tatenokai, the Chūkaku-ha and Kakumaru-ha were illustrative of the difficulties experienced by the urban leftists of 1970s Japan: slowly being whittled away despite the odd crackle and pop amidst the dying embers. The Kakumaru-ha also came under fire from the Shaseidō "Liberation Faction" (

Kaihō-ha) which had split off from the JSP-affiliated Zengakuren groups and would be expelled from the party in 1971. The Shaseidō Kaihō-ha would claim the lives of 20 Kakumaru-ha members by 1980, and would also be one of the three founding groups (along with the Chūkaku-ha and the Second Bund) of the "Senpa Zengakuren" (Three-Faction Zengakuren) in 1966. The Second Bund birthed the splinter group referred to as the "Red Army Faction" (

Sekigun-ha) which would be the precursor of both the United Red Army and the Japan Red Army urban guerrillas. The Raison d'être of the Sekigun-ha was typical of the Kanto urban guerrilla groups: their parent organisation was apparently insufficiently militant for their tastes. Most of their members were regional Japanese who had moved to Tokyo's elite universities. Isolated from their families, and embittered by the newfound knowledge that they were, regardless of their academic capacity, 'yokels' in the eyes of some of their old-money peers, they had turned to radical, iconoclastic politics. The Sekigun-ha would merge with the JCP Kanagawa Prefecture Committee (which had begun to operate in opposition to many of the JCP's core tenets) to form the United Red Army. The URA and its precursor groups had engaged in a number of robberies of banks and gun stores. Banding together to pool their complementary resources (i.e. guns and money), the formation of the URA was announced on July 15 1971 in a magazine the group had published named Jūka ("Gunfire"). The URA committed to "fight a war of annihilation with guns, against the Japanese authorities". It was not long, however, until the URA devolved into self-dissolution as a result of a cultish obsession with "self-crit" and "struggle sessions". Physical punishment from the autocratic and increasingly-unhinged co-leaders, Mori Tsuneo and Nagata Hiroko, resulted in several deaths. By early 1972, the remaining members of the URA had largely been arrested by the police. A few members of the group had attempted to fight their way out of Tokyo, but died in battle with Yakuza thugs and the Tatenokai [179]. Whilst the URA was operating in Japan, a small core group of militants led by Sekigun-ha leader Fusako Shigenobu left Japan for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Trained in urban guerrilla tactics by the Korean military, this small group which became known as the "Japan Red Army" would be sent to Europe, where they engaged in a number of operations in support of urban guerrilla groups in Italy, France and Germany.

In 1972, the long-running Prime Minister Eisaku Satō was succeeded by Kakuei Tanaka, who would soon become known by the nickname of the "Shadow Shogun" (Yami-Shōgun). Tanaka was far from a paragon of civic virtue: his tenure would later be infamous for a number of embezzlement scandals, where he was found guilty but never punished; the Japanese Supreme Court would keep these as "open cases", accepting the appeals but never actually processing the case, thus allowing Tanaka to remain free and politically-active. Tanaka had placed himself at the centre of a number of political axes: he has myriad contacts in the American diplomatic corps, had built a political machine in his home region of Niigata through the

Etsuzankai association. Tanaka's close ties to the construction industry also meant close cooperation with Yakuza syndicates. His ascension to the post of Prime Minister was the emblematic beginning of the leadership of the right wing of the LDP.

---

[177] Historically, he never sought a career in politics, but would commit ritual suicide after a failed attempt to induce army troops into a coup d'etat.

[178] IOTL, the grand total was 100, but ITTL the Tatenokai movement grew at a greater rate.

[179] Historically, the remnants of the URA were arrested after a hostage situation at Asama Sanso Lodge. The trial process after was highly irregular.